calsfoundation@cals.org

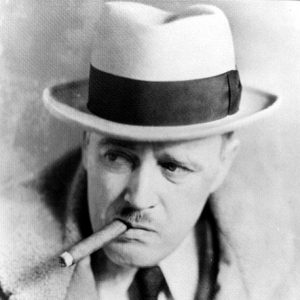

Vance Randolph (1892–1980)

Vance Randolph was a folklorist whose wide-ranging studies in the traditional culture of the Ozarks made him famous with both academic and popular readers from the 1930s to the present.

Vance Randolph was born on February 23, 1892, in Pittsburg, Kansas, to John Randolph, an attorney and Republican politician, and Theresa Gould, a public school teacher. He was the eldest of three sons. Born to the respectable center, he was as a young man attracted to the margins, to the rich ethnic and cultural diversity and radical politics of the region’s mining communities. He dropped out of high school and published his first writing for leftist periodicals such as the socialist Appeal to Reason, published in nearby Girard. He graduated from the local college (now Pittsburg State University) in 1914.

Randolph considered an academic career on at least two occasions. He completed an MA in psychology at Clark University in 1915, after which he unsuccessfully sought pioneer anthropologist Franz Boas’s support for graduate work at Columbia University, where he wanted to study Ozark mountain people. In 1921, he enrolled in the doctoral program in psychology at the University of Kansas, though he never completed the degree.

By 1920, Randolph had moved to the Ozarks, settling first in Pineville, Missouri. He married a local woman, Marie Wardlaw Wilbur. He made his living writing for sporting magazines and for pioneer paperback book publisher E. Haldeman-Julius . He also made a name for himself as a student of traditional Ozark culture. Randolph used many pseudonyms, writing for money as “Anton S. Booker,” “William Yancey Shackleford,” and “Belden Kittredge,” among others. He wrote as Vance Randolph when writing about Ozark folklore.

His first scholarly efforts were in dialect studies and folk belief. Folk belief provided the material for his first Journal of American Folklore article in 1927, while his dialect studies led to numerous publications in American Speech and Dialect Notes in the 1920s and 1930s. He eventually produced major, book-length works in both fields: Ozark Superstitions (1947), which was first published by Columbia University Press and later reissued as Ozark Magic and Folklore (1964), and Down In the Holler: A Gallery of Ozark Folk Speech (1953) from the University of Oklahoma Press. Before these major works, he wrote The Ozarks (1931) and Ozark Mountain Folks (1932). At the time, they were ignored by most academic reviewers and sometimes resented by Ozarkers themselves for their celebration of “backward” elements in the region’s culture. More recent students have recognized them as pioneering examples of what are now called folklife studies, and in the 1970s, especially, scholars began praising Randolph for his prescience in this and other areas.

Randolph collected folklore steadily throughout the 1930s and 1940s, even as he supported himself with everything from writing articles for sporting magazines to various works for juvenile readers—such as The Camp on Wildcat Creek (1934) and The Camp-Meeting Murders (1936)—and many books on topics ranging from biographies of western gunfighters and outlaws, such as Wild Bill Hickok: King of the Gunfighrters (1943), to botany and entomology, such as Life Among the Ants (1943), for the Little Blue Books series published by Emanuel Haldeman-Julius. Randolph also published an attempt at a serious novel, Hedwig (1935), and a collection of short fiction, From An Ozark Holler (1933).

He began collecting traditional music in the 1920s, when he sought to contact potential singers through a column in the weekly Pineville, Missouri, Democrat, but Ozark Folk Songs, the enormous collection issued by the State Historical Society of Missouri, may be his single most impressive work. It appeared in four volumes between 1946 and 1950. The 1950s also saw the publication of five volumes of Ozark folk tales, beginning with We Always Lie to Strangers (1951), followed by Who Blowed Up the Church House? (1952), The Devil’s Pretty Daughter (1955), The Talking Turtle (1957), and Sticks in the Knapsack (1958).

Randolph’s first wife died in 1937, and the couple had no children. For most of the 1940s and 1950s, he lived in Arkansas, mostly in Eureka Springs (Carroll County) but also in Fayetteville (Washington County). In March 1962, Randolph married Mary Celestia Parler, a folklore researcher and English professor at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville. He later published a collection of Ozark jokes and jests, Hot Springs and Hell (1965), and Ozark Folklore: A Bibliography (1972). Pissing in the Snow (1976), a collection of bawdy folk tales, became far and away his most popular book.

In 1978, Randolph was elected a Fellow of the American Folklore Society. He died on November 1, 1980, in Fayetteville and is buried in the National Cemetery there, as a consequence of a brief military service earlier in his life.

A supplement to his Ozark folklore bibliography, edited by Gordon McCann, appeared posthumously in 1987. Two more volumes of bawdy materials, Roll Me in Your Arms (1992) and Blow the Candle Out (1992), were edited by longtime Randolph admirer Gershon Legman.

For additional information:

Cochran, Robert. Vance Randolph: An Ozark Life. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1985.

Cochran, Robert, and Michael Luster. For Love and For Money: The Writings of Vance Randolph. Batesville: Arkansas College Folklore Archive Publications, 1979.

Husted, Bill. “Author in Nursing Home Still Writes About Ozarks.” Arkansas Democrat, April 4, 1976, pp. 1A, 24A.

Nelson, Sarah Jane. Ballad Hunting with Max Hunter: Stories of an Ozark Folksong Collector. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2023.

Randolph, Vance. Mildred, Quit Hollering and Other Ozark Folktales. With commentary by Curtis Copeland and Augustus Finch. Sikeston, MO: Acclaim Press, 2023.

Robert B.Cochran

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.