calsfoundation@cals.org

Religion

The number of people in Arkansas who believe in and practice a religious faith has always been high, with the greatest percentage identifying themselves as Christian and Protestant. Numerically, the largest denomination in the state is now Baptist, including its Southern, Missionary, Free Will, Primitive, and other branches. Because of privacy issues and the separation of church and state, it is difficult to arrive at exact statistics pertaining to church membership or affiliation. The U.S. government’s Census of Religious Bodies was discontinued in 1936.

Early Religion in Arkansas

Prior to European contact, little is known of Native American—in Arkansas, the Quapaw and Caddo groups—religious traditions. Attempts at reconstructions based on archaeology and later ethnography have been made, but recorded accounts begin with the arrival of Spanish explorers in the sixteenth century.

The first recorded Christian services in what is now Arkansas were conducted in 1541 by Roman Catholic priests with the Hernando de Soto expedition. The site was an Indian village referred to as Casqui near present-day Parkin (Cross County). A tall cross was erected, the stump of which may have been found by modern-day archaeologists, and de Soto and his men knelt before it. The Indian residents of the village were led to do the same, thus satisfying the requirement of Spanish colonial policy that native peoples be brought into the realm of Christendom.

The next European contact occurred when the French Jesuit explorer, Father Jacques Marquette, visited a Quapaw village a few miles above the mouth of the Arkansas River in 1673. Father Zenobe Membre, a Franciscan priest with the René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, party, conducted services near the same place nine years later. A tall column was erected, upon which was painted a cross, the arms of Bourbon France, and the year 1682. A quasi-religious ceremony was held during which Father Membre sang hymns and La Salle claimed sovereignty over the territory for the king of France. The religious aspects of the celebration had no known lasting effect on the Indians.

Arkansas Post was established near the mouth of the Arkansas River by Henri de Tonti in 1686. He promised to build a chapel and maintain a resident priest there, but no priest arrived until many years later. The site of the post was moved at least twice because of flooding, and the French population never grew beyond a few people. An attempt was made to revive the settlement in 1721, but when a Jesuit missionary arrived six years later, he reported that the post had been abandoned.

Throughout the rest of the eighteenth century, French and Spanish missionary priests visited Arkansas occasionally but never stayed long. Father Louis Carette, a Jesuit, arrived at Arkansas Post in 1750 but remained only until 1758. Not until 1796 was the “Parish of Arcanzas” created. Father Pierre Janin, its only priest, built a chapel there dedicated to St. Stephen, but he left after only three years.

The Roman Catholic Church

The next Catholic church in Arkansas was not built until 1834, when St. Mary’s Mission, the oldest Catholic congregation in the state, was established five miles south of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). The first Catholic school in the state was started there four years later by the Sisters of Loretto.

About 700 Catholics lived in Arkansas at the time of statehood. Most were scattered along the Arkansas River Valley from Little Rock (Pulaski County) to Pine Bluff and nearby New Gascony, French Town, and Plum Bayou (all in Jefferson County), Arkansas Post, Fort Smith (Sebastian County), and Napoleon (Desha County). Andrew Byrne, bishop of the newly created Diocese of Little Rock, arrived in Arkansas in 1844. To meet the increasing challenge of Protestants moving into the state, he built the first St. Andrew’s Cathedral, brought in priests, and founded new churches and schools. Byrne’s plans, however, were frustrated by the anti-foreign, anti-Catholic “Know-Nothing” movement of the 1850s. Founded largely in response to the recent influx of German and Irish immigrants to the United States, the Know-Nothings opposed, sometimes violently, the religion of these newcomers (mostly Catholic) and their enjoyment of alcoholic beverages. Political cartoons of beer-swilling Germans and whisky-soaked Irishmen were common in the newspapers of the day. Perhaps as a result of the influence of these depictions, the Catholic church at Helena (Phillips County) was burned in 1854, and by the time of Byrne’s death in 1862, there were only nine priests, a few nuns, and about 1,000 Catholics in the state.

Protestant Churches

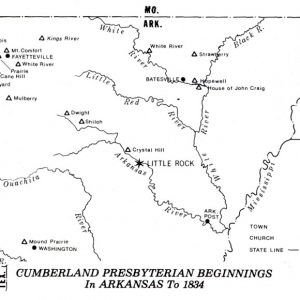

French and Spanish colonial law prohibited Protestant worship in their territories, but after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, American Protestant settlers soon outnumbered Catholics in Arkansas. Most numerous by the 1820s were Methodists and Baptists, with smaller numbers of Cumberland Presbyterians, traditional Presbyterians, a sprinkling of Episcopalians, and some traveling evangelists who did not adhere to any particular denomination. Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, while descending the White River in 1819, observed: “Here [about 19 miles south of ‘the Calico Rock’ in Izard County] some hunters were gathered to hear an itinerant preacher.”

Early Protestants in Arkansas were much affected by the second Great Awakening, which spread across the frontiers of Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee at the turn of the nineteenth century. Emotion, evangelism, and non-denominational worship were expressions of this movement. Before 1850, few congregations of any faith had a church building beyond a simple log or frame structure. Some met in private homes or in brush arbors during pleasant weather. Occasionally two denominations shared a building, alternating Sundays when a preacher was available. If there was not a preacher, Sunday School classes met for Bible study, hymn-singing, and prayer. In most rural communities, the church house was often used as a school house during the week, and sometimes the Masons or another lodge group would have a meeting room upstairs.

Pastoral salaries were low. Methodist preachers in 1833 were paid $34 per year if they were single, double that if they were married. More than twenty years later, an article in The Christian Repository stated that Baptist preachers were averaging less than $200 a year, and some were responsible for three or four churches. Preachers of all denominations farmed, taught school, or owned businesses to make ends meet. They were often paid “in kind” with garden vegetables, eggs, or hand-me-down clothes for their children. Few congregations provided housing for the preacher.

The level of pastoral education, excepting Presbyterians and Episcopalians, was very low in the early years. Most Protestant denominations honored a divine “call” to the ministry that was considered equal to educational training. One reason the Cumberland Presbyterians had separated from the main church body in 1810 was the requirement that preachers be formally educated.

Camp meetings were common in Arkansas during the nineteenth century. Simple brush arbors or open shelters called tabernacles were erected near a spring of good water. People came from miles around, bringing their own food and sleeping in their wagons or on the ground, to hear preaching several times each day and to join in singing favorite hymns. Eventually, some families put up small cabins. Although constructed of wood, these were referred to as “tents.” The social aspect of the camp meeting was as important as the spiritual to early Arkansans. A number of church campgrounds are still operating today, although participants are more likely to stay in recreational vehicles. The oldest is Ebenezer Campground, established by Methodists in Howard County. Meetings have been held there most summers since 1822.

Methodist

The Methodist Episcopal Church in America was completely separated from the Episcopal or Anglican Church following the American Revolution. It enjoyed a well-organized structure, designed by John Wesley himself, which enabled it to grow rapidly after preachers went into new territory. The first Methodist Episcopal preachers were sent officially into what is now northern Arkansas by the Tennessee Conference in 1815. A separate Arkansas Conference was organized in Batesville (Independence County) in 1836, and the ninety-two members reported in 1816 grew to nearly 25,000 by 1861.

The Methodist Protestant Church separated from the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1830, and the Methodist Episcopal Church itself divided over the issue of slavery in 1844. A small number of congregations in Arkansas, located mainly in the north and west, remained loyal to the mother church, the so-called “northern” branch, but the new Methodist Episcopal Church, South, became the largest denomination in the state throughout most of the nineteenth century.

Baptists

Records of early Baptist activity in Arkansas are scanty because there was no centralized structure to gather statistics until after 1848. It is known that missionaries from southern Missouri rode the “destitute regions” of the Missouri Territory in 1817 and organized Salem Church at Fourche-a-Thomas in present-day Randolph County the following year. Other missionaries were active in what is now Washington County and in the southwest along the Arkansas-Louisiana border.

Silas Toncray, a minister and jeweler, organized a church in Little Rock in 1824 and also helped create the Little Rock Association, the first association of independent Baptist congregations in the state. Baptist work in the Little Rock area, however, was delayed by competition with Restorationist or Campbellite preachers who converted a number of Baptist congregations. First Baptist Church in Little Rock was not firmly established until 1868.

The Arkansas Baptist State Convention was created at Tulip (Dallas County) in 1848. Baptists had also split over the issue of slavery in 1845, and the Arkansas State Convention eventually, in 1861, affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention. Better organization and dedicated missionary work led to an increase in membership in the state from about 375 members in 1850 to more than 11,000 by 1860. Many congregations, however, were not comfortable with the structure and cooperation required by a statewide convention. Most were small, rural, and fiercely independent. Some had combined into regional associations, but these had no official ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

Baptist history in Arkansas after the Civil War was dominated by the struggle between those who wanted to strengthen and consolidate the State Convention and those who condemned such a move. Those who favored consolidation and cooperation were opposed by equally faithful adherents who felt that denominational centralization violated pure Baptist doctrine. They insisted that boards and conventions were not apostolic, and they opposed the employment of paid staff workers.

The Landmark movement first appeared in the 1850s, when conservative Baptists called for stricter adherence to the “landmarks” of the Baptist faith. These included supremacy of the local congregation and tracing Baptist heritage back to apostolic roots. Some congregations left the State Convention in 1902 and organized the General Association of Arkansas Baptists (later the State Association of Arkansas Baptist Churches). In 1924, the Landmarkers withdrew completely from the Convention and formed the American Baptist Association, a voluntary body made up of independent and unaffiliated congregations. Separate statistics were not published until 1921, but during those two decades, the Arkansas Baptist State Convention lost about half of its forty-seven associations and a third of its members.

Adhering to their strong belief in congregational autonomy, Baptist churches became affiliated with the Southern (the most numerous), American, Free Will, General, Missionary, Primitive, and other independent branches of their denomination. Southern Baptists retained a more restrictive convention structure; the others preferred voluntary membership in looser associations. Landmark congregations continued completely independent and do not consider their church a “denomination.”

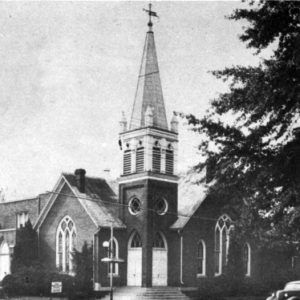

Presbyterians

The third largest Protestant denomination in Arkansas in the early nineteenth century was the Presbyterian Church. A seceding church was founded in 1810 calling itself Cumberland Presbyterian because it was founded in the Cumberland River valley in Tennessee. Some sources claim that John Carnahan, a Cumberland Presbyterian minister, may have preached the first Protestant sermon in what is now Arkansas (circa 1812, at Crystal Hill in Pulaski County). A Cumberland presbytery was established in 1823, and a number of small churches were founded during that decade. Their numbers were small, and they remained largely rural.

The first congregation organized by the parent Presbyterian Church, which tended to be more urban, was First Church, Little Rock, founded by missionary James W. Moore in 1828. The Presbytery of Arkansas was formed in 1835, and the Synod of Arkansas, consisting of three presbyteries, was constituted in 1852. Early clergy included missionaries at Choctaw and Cherokee missions in the state. By 1860, Presbyterians and Cumberland Presbyterians combined numbered about 2,500 members in Arkansas.

Presbyterians also divided over slavery. Mostly northern churches constituted the Presbyterian Church of the United States of America (PCUSA), while churches in the southern states combined to form the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS). The PCUSA considered itself a national church despite the Civil War and continued to maintain churches in Arkansas right up to the ultimate reunion. The breach between the two denominations, north and south, was not healed until 1983, when one united church was created, retaining the name the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. A few congregations refused to participate in the merger and continue in the state today calling themselves the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA).

An attempt was made in 1906 to reunite Presbyterians and Cumberland Presbyterians. Some Cumberland congregations voted for union, while others chose to reorganize and continue as Cumberland Presbyterians.

Christian, Disciples of Christ, Churches of Christ

What is known as the Restorationist Movement originated in part from camp meetings in Kentucky in the early nineteenth century. Its adherents sought to return Protestant faith and worship to the simplicity of the New Testament. They felt that all the trappings of denominationalism contaminated the purity of the original church established by the apostles. Thomas Campbell, his son Alexander, and Barton Stone were leaders of this movement. Their followers became intermingled by the early 1830s—some calling themselves Christians and some Disciples—but few records survive from their early congregations. Their preachers were already at work in Arkansas by that time. This movement would culminate by the end of the nineteenth century in the formation of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) and the establishment of the independent Churches of Christ. The latter churches do not consider themselves part of a denomination, but they were first identified as autonomous by the Federal Census Bureau in 1906.

Episcopalians

Organized Episcopal Church activity began in Arkansas through the efforts of Missionary Bishop Leonidas Polk (1838–1840). Episcopalians were few in number, and there were no organized parishes until Polk made two missionary journeys around the state during his tenure, establishing Christ Church in Little Rock and St. Paul’s in Fayetteville (Washington County). Slow development continued until 1860, when there were twelve organized parishes and about 400 members, but most of the congregations did not have a church building or a full-time rector. Episcopal churches in the South also split from their national body at the beginning of the Civil War but did not form a separate denomination and quickly reunited when the war ended.

Jews

The first known Jewish settler in Arkansas, Abraham Block, settled in Washington (Hempstead County) in 1823 and established himself as a prosperous businessman. A few more Jews followed in the 1830s and 1840s, some as peddlers traveling out of New Orleans, Louisiana, and Memphis, Tennessee, and some as clerks. Most became successful merchants and cotton brokers in the larger towns. The first congregation was B’nai Israel, organized in Little Rock in 1866. By 1872, this congregation had built a brick temple and elected its first rabbi, Jacob Bloch.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons)

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, founded in 1830 in New York by Joseph Smith, had missionaries in Arkansas as early as 1835, but no congregations were organized that early. In 1875, missionaries baptized nearly ninety people in the Des Arc (Prairie County) area, but that entire congregation moved to Utah two years later. Hostility against Mormons abounded in nineteenth-century Arkansas, and their numbers remained small. This animosity was manifest in the 1857 murder of Parley Pratt, a key figure in the early history of the church, and may have led, in part, to the Mountain Meadows Massacre later that year. A wagon train, made up largely of Arkansans, was traveling across Utah when it was attacked by a party of Mormons and some of their Indian allies.

Native American Missions

Missionary work among Indians in Arkansas began with the early French and Spanish Catholic priests and continued through the 1830s as the Southeastern tribes passed through the state on their way to Indian Territory. Many of them were already Christian and were accompanied by their own native preachers such as the Methodist John Fletcher Boot, a Cherokee, and William Winans Oakchiah, a Choctaw. At least seven of the twenty-seven preachers present at the first Arkansas Methodist Conference session in 1836 were associated with Indian mission work, had Indian wives, or were part Indian themselves.

Dwight Mission, founded by Presbyterian missionaries in 1820 near what is now Russellville (Pope County), was the first and best-known Indian mission school. It was closed in 1829 and reopened later in Oklahoma. Arkansas Methodists operated many mission schools along the western border from 1831 until a separate Indian Mission Conference was organized in 1844.

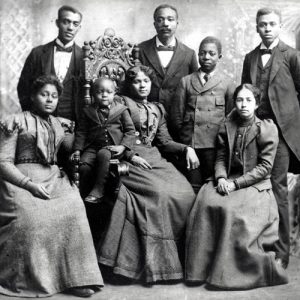

African American Churches

Most Christian denominations in Arkansas had members among the slave population before the Civil War. Slaves often attended church with their white enslavers, although they were usually seated separately, perhaps in a balcony. Sometimes services were held for them on Sunday afternoons or at other times, but usually in the white church and with a white preacher. A young Methodist preacher in Batesville in 1841 recorded his attendance at preaching for slaves at the courthouse there. “I tried to exhort a little,” he wrote, “but they out-hollered me, so I quit.”

First Methodist Episcopal Church, South, in Little Rock, however, organized a separate congregation for its slave members in 1854. This group went over to the Methodist Episcopal (northern) Church after the federal occupation of Little Rock, and its preacher, William Wallace Andrews, became one of the first Black Methodist preachers in the state when he was ordained by the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1865. A school Andrews had operated in Wesley Chapel was endorsed by the Freedmen’s Aid Society of that church and later became Philander Smith College.

Black Arkansans, most of whom were Baptist or Methodist, were able to establish their own churches after emancipation. The Methodists had four choices. One was the Methodist Episcopal Church (northern), which was attractive because of its history of opposition to slavery and because its Freedmen’s Aid Society founded a number of schools across the state. Although Black worshipers were welcome as members of this church, they remained in segregated congregations.

The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church was another choice and soon became the largest Black Methodist denomination in Arkansas. The first congregation was Bethel Church in Little Rock, organized about 1863 by Nathan Warren, a successful businessman. There were sixteen congregations in the state by 1868, when the AME Arkansas Conference was established with Bishop James A. Shorter presiding.

The Colored (now Christian) Methodist Episcopal Church (CME), was founded as a segregated conference by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, and became a completely separate denomination in 1870. Lastly, a few congregations of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Zion (AMEZ), were organized in the state after the Civil War.

One of the first Black Baptist churches in Arkansas was organized in Little Rock as a slave congregation in 1845. This church, along with others like it, formed the First Missionary Baptist Association in 1867. By the 1880s, there were nine associations affiliated with the National Baptist Convention, USA, to which most Black Baptist churches in the state still belong. No separate Presbyterian or Episcopal denominations were established, although there were some separate black congregations.

Immigration and Religion

After Reconstruction, German immigrants, attracted by cheap land and jobs with the railroads, expanded the number of Lutherans in Arkansas. There had been only one Lutheran church in the state before the war—Long Prairie, south of Fort Smith, which was established in 1852. In 1868, First Lutheran Churches were founded in Fort Smith and Little Rock.

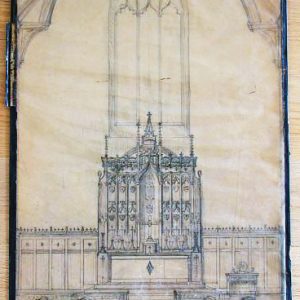

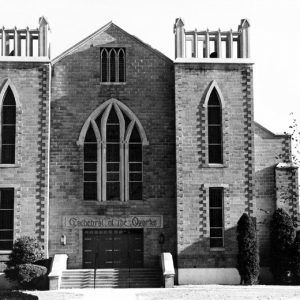

Other Germans were Roman Catholic and contributed to a rejuvenation of Catholicism in the state. This effort was enhanced in 1867 with the arrival of Bishop Edward Fitzgerald. He encouraged Catholic immigration into Arkansas and supervised the construction of a new St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Little Rock, completed in 1881. The bishop invited German-speaking priests and nuns to organize churches and schools, and more than thirty were founded between 1875 and 1899, including St. Scholastica’s Convent and School at Shoal Creek (Logan County) in 1878 and Subiaco Abbey and Academy at Subiaco (Logan County) in 1891.

Other Catholic churches were founded by immigrants—Poles formed the Immaculate Heart of Mary at Marche (Pulaski County) in 1880, and Slovaks formed Saints Cyril and Methodius at Slovak (Prairie County) in 1898. An Italian community settled at Sunnyside, near Lake Village (Chicot County), and formed a Catholic church there in 1895. Three years later, a large portion of the community moved to Tontitown (Washington County), near Fayetteville, where the church they founded, St. Joseph’s, still thrives.

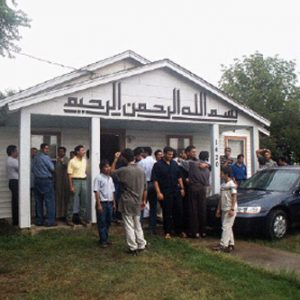

Several cities in Arkansas now have Islamic centers; the mosque in Jonesboro (Craighead County) was first built to serve Arabic students attending Arkansas State University. There are Buddhist temples in Fort Smith and Buddhist societies elsewhere, as well as Hindu associations. The Bahá’í faith is also represented in Arkansas.

Denominational Schools and Services

Nearly all denominations established secondary schools and colleges in Arkansas in the nineteenth century. Cumberland Presbyterians founded Cane Hill College at Cane Hill (Washington County) in 1858. This school closed in 1891 when a new institution, Arkansas Cumberland College, was opened in Clarksville (Johnson County). After being acquired by the Presbyterian Church (PCUSA) in 1920, the name was changed to College of the Ozarks. In 1987, it achieved university status and was renamed University of the Ozarks.

Shortly after the establishment of the state-supported University of Arkansas in 1871, Presbyterians (PCUS) founded Arkansas College at Batesville (1872). Now known as Lyon College and still operated by the Synod of the Sun, it is the oldest independent institution under continuous operation in the state.

Methodists opened a number of colleges in the nineteenth century and operated twenty district high schools throughout the state at various times. Most of these had been replaced by public high schools by the end of the century, and only three colleges survived: Central Collegiate Institute for young men founded at Altus (Franklin County) in 1876, Galloway College at Searcy (White County) in 1889, and the coeducational Arkadelphia Methodist College in Arkadelphia (Clark County) in 1890. All three were eventually merged as Hendrix College in Conway (Faulkner County).

Baptist associations also opened a number of colleges and academies in the 1870s and 1880s. Judson University in Judsonia (White County) was founded by a group of northern Baptists working as missionaries in the South. Shiloh Institute in Springdale (Washington and Benton Counties), Red River Academy in Arkadelphia, and Buckner College in Witcherville (Sebastian County) were other Baptist institutions. The Arkansas Baptist State Convention established Ouachita Baptist College (now Ouachita Baptist University) in Arkadelphia in 1886. Most of the other Baptist schools had closed by that time.

Ouachita Baptist College, unlike most of the other denominational schools, was coeducational from the beginning, although Central College for Women was also established by Baptists in Conway in 1892. Two other Baptist schools, Mountain Home College (Baxter County, 1893–1933) and Jonesboro Baptist College (Craighead County, 1903–1935), closed during the Great Depression. Central Female College was moved to North Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1948 and closed permanently in 1950. The property in Conway and the name Central College were acquired by the Arkansas Missionary Baptist Association in 1952, and the school was reopened as Central Baptist College. In 1941, the Arkansas Baptist State Convention assumed control of Southern Baptist College at Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County), renaming it Williams Baptist College in 1991; in 2018, the name was changed to Williams Baptist University.

Three historically Black denominational colleges still in existence were founded in Little Rock during the nineteenth century. Philander Smith College was opened in 1877 by the Methodist Episcopal Church as Walden Seminary; Arkansas Baptist College was started in 1884 as a seminary for ministerial students; and Shorter College was opened in 1886 as Bethel Institute by the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Shorter moved briefly to Arkadelphia, then to its present site in North Little Rock, where it operates as a two-year institution.

To address community needs, many churches operate soup kitchens, clothes closets, and food banks. The growing population of elderly people with limited incomes has led churches to establish retirement homes. One example is Good Shepherd in Little Rock, operated jointly by the Catholic, Episcopal, and United Methodist churches. Baptists, Catholics, and Methodists operate hospitals and health care agencies in the state, for example Baptist Health and CHI St. Vincent in Little Rock and St. Bernards Medical Center in Jonesboro.

Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century Developments

In 1906, a federal census of religious bodies in the United States revealed a great increase both in church membership and in the number of denominations. In Arkansas, Baptists had overtaken Methodists as the largest denomination in the state. Almost eighty percent of Arkansans were either Baptist or Methodist.

Newer denominations in the state with enough members to be recognized separately in the 1906 census were the Seventh-Day Adventists (Arkansas-Louisiana Conference organized in 1888); Church of Christ, Scientist; Church of the Brethren; Amish; Salvation Army; and Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints; and three predominantly Black denominations with Arkansas roots that had grown out of the Holiness movement of the late nineteenth century: the Church of the Living God, founded at Wrightsville (Pulaski County) in 1889; the Church of God in Christ, founded by former Baptists in 1897; and the Free Christian Zion Church of Christ, founded in Redemption (Perry County) in 1905.

Other new denominations had developed out of the Holiness movement. Seeking what Methodist pioneer John Wesley called “entire sanctification” or “the second blessing,” some conservative or traditionalist Protestants wanted a more intensely emotional personal faith. They were not comfortable with the growing formality of worship in larger sanctuaries or with the impersonal nature of larger congregations. The Church of the Nazarene was developed, largely by former Methodists, as a separate denomination in the first decade of the twentieth century, retaining much Methodist doctrine and polity.

The Assemblies of God were organized similarly in 1914. Each congregation is independent but is allied with the assembly in the same way a Baptist congregation affiliates with an association.

The Depression of the 1930s brought about the demise of a number of small churches and denominational colleges in the state. Another development was the near-bankruptcy of the Baptist State Convention in 1936. During the expansive 1920s, many of its churches had over-extended themselves in building programs. A debt settlement was negotiated in 1938, but the Convention completely paid off the loans by 1952.

One success of the 1930s was the reunification of the Methodist Protestant, Methodist Episcopal, and Methodist Episcopal, South, churches in 1939. Black members of the Methodist Episcopal Church, however, remained segregated in a separate jurisdiction and separate conferences. In 1968, the Methodist Church merged with the Evangelical United Brethren, forming the United Methodist Church. Complete racial integration of the United Methodist Church in Arkansas came about officially in 1972. The three Black Methodist denominations (AME, AMEZ, and CME) have remained separate and distinct.

The “Historical Records Survey of Churches and Religious Organizations,” a Works Progress Administration (WPA) project completed in 1942, added information about other denominations that arrived in Arkansas in the twentieth century—the Christadelphian Society, Churches of God, and Jehovah’s Witnesses, for example. The number of Jewish congregations had increased to eleven, and there were both Greek and Russian Orthodox churches in the state. Many independent churches were enumerated in this survey, but Baptists and Methodists were still the largest denominations.

The second half of the twentieth century brought more changes to religion in Arkansas. Contributions increased, reflecting the relative prosperity of the time, and increased building and improvements raised the value of many church properties.

Following the gradual change from a rural to an urban population, hundreds of small country churches closed. Some continue with part-time preachers or lay speakers, and others are maintained to be used occasionally for funerals or “homecomings.” As cities grew, it became common for the large downtown churches to move to the suburbs, where they built larger sanctuaries with separate educational buildings, family life centers, gymnasiums, and arts and crafts and theater facilities. The extra space at these so-called “mega-churches” is often made available to the public for Boy or Girl Scouts, Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, blood donation drives, health clinics, and other community activities.

Church programs have expanded far beyond Sunday services and Wednesday night prayer meetings. Modern-day churches have baseball teams, daycare centers, orchestras, drama organizations, and special activities for youth and senior citizens. Many churches include modern music in their services, and some have casual or “blue jeans” services at a different time from the regular worship hour.

Along with expanded facilities and programs, most larger churches have increased their paid staff to one or more associate pastors and youth ministers, as well as paid organists, pianists, and choir directors. They also employ secretaries, bookkeepers, receptionists, and custodians.

The second half of the twentieth century also brought the rapid growth of independent, non-denominational congregations with names such as Agape Church, Believers’ Outreach, and Bible Fellowship. Sometimes developed through the ministry and evangelism of one charismatic preacher, these congregations have grown in numbers through word-of-mouth testimony and in wealth through tithing. Some began by holding services in vacant houses or stores and now have large sanctuaries. Their ministry appeals to people who seek something different from the traditional worship offered by mainline denominations. Some evangelical congregations that appeared in growing suburban areas in the 1980s adopted the strategy of choosing generic names for their new churches. A number of Baptist churches particularly have changed their traditional names in order to obscure their denominational roots.

The proliferation of mega-churches, associated with the declining importance of denominational ties, is one of the major trends of present-day religion in Arkansas. Tied to this characteristic is the continuing decline in membership and attendance at the mainline Protestant churches. Another trend has been growth in the number of private church-related elementary and secondary schools in the state. The twenty-first century has witnessed a steady growth in the influence of conservative Christians, typically affiliated with the Republican Party, in state government. In 2014, Republicans won all the state constitutional offices, as well as a majority in both houses of the Arkansas General Assembly. Bills passed during the 2015 legislative session included the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, a bill requiring the placement of a Ten Commandments monument on the Arkansas State Capitol grounds, and several bills restricting abortion rights in the state. Some form of religion may be a constant in the lives of most Arkansans, but the reorganization and reshaping of Arkansans’ religious faith and institutions continues.

The 2020 U.S. Religion Census found that Southern Baptists remained the largest religious group in Arkansas, followed by independent or non-denominational churches, Roman Catholics, United Methodists, and Missionary Baptists. Significant growth could be seem in the number of adherents of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, while mainline Protestants continued to decline in number. Evangelical denominations also declined in absolute numbers while maintaining their standing per capita; the number of Southern Baptists in Arkansas had declined by roughly eight percent compared to 2010. The same census reported that Arkansas had a larger number of houses of worship per 100,000 people than any other state in the union, although the state was ranked sixth in terms of worship attendance.

For additional information:

Arnold, Morris S. Unequal Laws Unto a Savage Race: European Legal Traditions in Arkansas, 1686–1836. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1985.

Barnes, Kenneth C. The Ku Klux Klan in 1920s Arkansas: How Protestant White Nationalism Came to Rule a State. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2021.

Britton, Nancy. Two Centuries of Methodism in Arkansas, 1800–2000. Little Rock: August House Publishers, 2000.

Bureau of the Census, Religious Bodies, 1906. Department of Commerce and Labor, Bureau of the Census. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1910.

Campbell, Thomas H., et al. Arkansas Cumberland Presbyterians 1812–1984: A People of Faith. Memphis: Frontier Press, 1985.

Giggie, John M. After Redemption: Jim Crow and The Transformation of African American Religion in the Delta, 1875–1915. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Glazier, Rebecca A. Faith and Community: How Engagement Strengthens Members, Places of Worship, and Society. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2024.

Harvey, Paul. Southern Religion in the World: Three Stories. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2019.

LeMaster, Carolyn Gray. A Corner of the Tapestry: A History of the Jewish Experience in Arkansas, 1820s–1990s. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Lockwood, Frank E. “Adding It All Up.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, November 19, 2022, pp. 4B, 5B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/nov/19/adding-it-all-up/ (accessed July 7, 2023).

McDonald, Margaret Simms. White Already to Harvest: The Episcopal Church in Arkansas 1838–1971. Sewanee, TN: University Press of Sewanee, 1975.

Mead, Frank S. Handbook of Denominations in the United States. Revised by Samuel S. Hill. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1985.

Payne, Wardell J., ed. Directory of African American Religious Bodies. Washington DC: Howard University Press, 1995.

Taylor, Orville W. “Arkansas.” In Encyclopedia of Religion in the South, edited by Samuel S. Hill. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1984.

Williams, C. Fred. A System and a Plan: Arkansas Baptist State Convention, 1848–1998. Franklin, TN: Providence House Publishers, 1998.

Williams, Johnny E. African American Religion and the Civil Rights Movement in Arkansas. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003.

Woods, James M. Mission and Memory: A History of the Catholic Church in Arkansas. Little Rock: August House Publishers, 1993.

Wright, R. R., Jr., comp. The Encyclopedia of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Philadelphia: Book Concern of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, 1947.

Nancy Britton

Batesville, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.