calsfoundation@cals.org

Mountain Home (Baptist) College

Mountain Home College (MHC)—known also as Mountain Home Baptist College—operated from 1892 to 1933 in Baxter County. Despite a troubled history, the school played an important role in education in the upper White River valley.

As education became more important in the late nineteenth century, Baptists sought to improve not only the educational level of the clergy but also of the laity. In 1889, the White River Baptist Association resolved that since so many public schools were “under the influence of infidel and worldly sentiments,” there should be a Baptist college in their region. The Baptists also noted that the Methodists had established the Yellville Institute in Marion County.

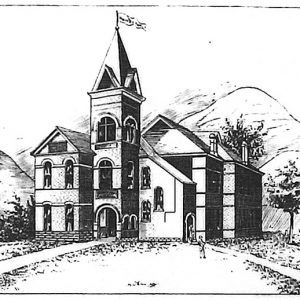

The school was located in Mountain Home (Baxter County), which subscribed $5,000 of the total $9,450 that was needed to start the school. Dr. William Smythe Johnson was the first president when the school opened officially on September 20, 1892. The ten-and-one-half-acre site had a Gothic brick building. Johnson was succeeded by Michael Shelby Kennard, a once prominent editor as well as a noted postwar educator, who headed the school for two years. The first bachelor’s degree was granted to Walter E. McLeod, who became a well-known educator and writer. Subsequent college presidents found that Baptists were far more willing to subscribe than they were actually to pay, so the school’s existence depended on local support.

The college was closed between 1898 and 1899 for lack of money but reopened under the leadership of J. G. Howell. Closed again for lack of money in 1901–1902, it reopened in 1902 as the Mountain Home-Ouachita Academy, with the board of the school having transferred the title to Ouachita Baptist College (now Ouachita Baptist University). It remained the Mountain Home-Ouachita Academy until 1911. Ouachita Baptist College president John W. Conger strongly supported it and sought money from the state convention. The new president, Louis A. Morton, raised $500 in 1903 to reopen the school. A re-acquired stone building that had been lost to debt earlier was turned into the girls’ dormitory. A friend of Governor Jeff Davis, Morton secured military hardware and opened a military department at the college. The school added baseball in 1906 and basketball in 1907, but only half of its 300 students regularly attended classes. Apparently, after Morton left in 1906, college classes ceased. Between 1906 and 1908, a subscription school operated on the site. Between 1908 and 1910, the Mountain Home public school used the buildings. During the 1910–11 school year, a “normal training high school” (a school used to train teachers) used the buildings, and a second normal school operated the next year. During 1912–13, normal school use continued, but some college classes may have been held, although between 1906 and 1916 there was no direct Baptist financial support.

Rebirth came in 1916 when, under the presidency of Henry Frankin Vermillion, some $900 worth of repairs went into the main building, and the twice-lost dormitory was regained. Money came from State and Home Mission Boards of the Southern Baptist Convention. Mission schools were intended to reach students in the remote mountain areas of the South. Southern Baptists established five academies, located at Maynard (Randolph County), Blue Eye (Carroll County), Hagarville (Johnson County), Parthenon (Newton County), Mount Ida (Montgomery County), with Mountain Home College being the flagship institution. During the 1916–17 year, there were six teachers and eighty-four pupils. Vermillion personally absorbed the deficit. The total enrollment the following school year stood at 100. President Hugh Dudley Morton, Vermillion’s successor, promised that “it is our aim to be a good Junior college,” but the youngest students started at the sixth grade.

The school’s best years came in the 1920s as town high schools slowly arose in the region. The college expanded to twenty-seven acres, and enrollment in the 1923–24 school year was 180, thirty-one of whom were ministerial students. Twenty-six counties, six states, and Canada were represented, and there were eleven faculty members. Sports were featured, and the program found a strong supporter in Tom Shiras, editor of the Baxter Bulletin. A campus newspaper, Ozark Echoes, recorded the doings of students, faculty, and alumni. By 1927, there were 265 students and a library of 7,000 volumes. The high school had grade-A status, and the junior college received formal accreditation from the American Association of Junior Colleges. By 1927, the forty acres had twelve buildings.

In 1927, state Baptists consolidated property ownership of the mission schools and the college, which they then mortgaged, using the money mostly to pay the debts of Central College in Conway (Faulkner County). The income promised to MHC from these complex transactions never materialized. Problems were compounded because the large churches for years had not collected money for the school, and half of the convention’s long-promised amounts never reached the school. The Home Mission Board ended its involvement in 1924, giving the Arkansas Baptist State Convention full responsibility for the school. From 1927 to 1929, the board sent only $250 per annum in aid. By 1927, the school’s deficit stood at $24,909.77.

Local leaders raised $4,000 in 1928, permitting the school to continue to the end of the school year, but it closed until the fall of 1930, when L. G. Whitehorn took over with promises of Baptist financial support that failed to materialize. One person familiar with the internal fight held that “a very few in places of power” sabotaged the school. L. B. Traynor then attempted to run it as a work school, but the end came for good in 1933. The college’s books went to the public library; Hugh D. Morton got possession of the administration building, then rented it to the public schools, which used it until 1939. Then it became a dormitory for workers building the Norfork Dam. Condemned in 1945, it was razed in 1964. The girls’ dormitory, the only building still standing, became a funeral parlor.

The school’s nearly perpetual upheavals reflected the difficulty in making higher education profitable or even self-sustaining. The Baptists had created too many schools, and they failed to implement realistic plans to support them. Locally, the lack of continuity and the recurring crises eroded support locally for higher education. When the first opportunity came to get a junior college in the early 1970s, voters rejected the measure.

For additional information:

Blevins, Brooks. “Mountain Mission Schools in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Winter 2011): 398–428.

Messick, Mary Ann. History of Baxter County, 1873–1973. Mountain Home, AR: Mountain Home Chamber of Commerce, 1973.

Morton, Hugh D. A History of the Ozark Division, Mountain Mission Schools of the Home Mission Board, Southern Baptist Convention. Russellville, AR: 1958.

Mountain Home Baptist College Miscellaneous Materials. Microfilm, two rolls. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Wasson, Michele Roussel. “Gem of the Ozarks: A History of Mountain Home College, 1890–1934.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1982.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Mountain Mission Schools

Mountain Mission Schools Mountain Home College

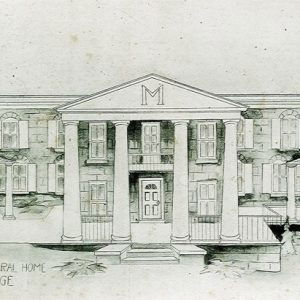

Mountain Home College  Mountain Home College Dorm

Mountain Home College Dorm  Mountain Home Baptist College

Mountain Home Baptist College  Mountain Home Baptist College Girls' Dormitory

Mountain Home Baptist College Girls' Dormitory

My grandfather, Alvie Boyd, tore the old college down. The wood was re-used to build his barn, which still stands on West Road just west of Mountain Home. The lumber has withstood numerous years and has so much history tied to it.