calsfoundation@cals.org

Craighead County

| Region: | Northeast |

| County Seats | Jonesboro, Lake City |

| Established: | February 19, 1859 |

| Parent Counties: | Greene, Mississippi, Poinsett |

| Population: | 111,231 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 707.16 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

3,066 |

4,577 |

7,037 |

12,025 |

19,505 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

27,627 |

37,541 |

44,740 |

47,200 |

50,613 |

47,303 |

52,068 |

63,239 |

68,956 |

82,148 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

96,443 |

111,231 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

80,639 |

72.5% |

| African American |

18,473 |

16.6% |

| American Indian |

356 |

0.3% |

| Asian |

1,692 |

1.5% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

61 |

0.1% |

| Some Other Race |

3,446 |

3.1% |

| Two or More Races |

6,564 |

5.9% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

6,727 |

6.0% |

| Population Density |

157.3 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$47,286 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$26,948 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

16.6% |

|

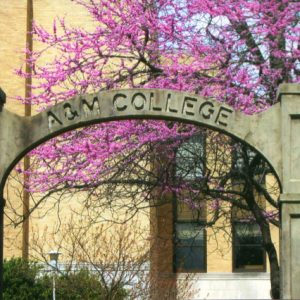

Craighead County is located in northeast Arkansas and was created as Arkansas’s fifty-eighth county in 1859. It is unusual not only in the circumstances of its creation and naming but also in that it has two county seats, Jonesboro and Lake City. The unique formation called Crowley’s Ridge runs through its center. Along with Jonesboro and Lake City, Craighead County also includes the towns of Bay, Black Oak, Bono, Brookland, Caraway, Cash, Claunch, Egypt, and Monette. It is the home of Arkansas State University (ASU), one of the state’s largest universities.

Pre-European Exploration

Of significance for early habitation of Craighead County is Crowley’s Ridge, a crescent-shaped outcropping running roughly from Cape Girardeau, Missouri, to Helena-West Helena (Phillips County). It rises 250–500 feet above the flat alluvial plains around it and is the highest point in northeast Arkansas. The ridge was safe from periodic floods that plagued the surrounding lowlands. Native Americans who inhabited the region lived both on the highlands of the ridge as well as the surrounding lowlands.

European Exploration and Settlement

Beginning in the mid-1500s, European explorers, starting with Hernando de Soto, came to northeastern Arkansas and the high ridge. Journals of the de Soto expedition noted frequent contacts with native peoples. Though they did not establish permanent settlements in the area, European explorers gave the area a few place names. For example, the town of Bay gets its name from French explorers who noted a large low-lying area where water stood most of the year and called it the Big Bay. Shortly before the Louisiana Purchase, some groups of Shawnee, Delaware, and Cherokee moved west of the Mississippi River and through the area.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812 kept many potential settlers away from northeast Arkansas and induced the few Native Americans there to move elsewhere, but about five years later, immigration to the area began increasing due to allayed fears of earthquakes and the attractiveness of the bounties given to veterans of the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. An act of Congress in 1820 continued the land bounty program, and the Bounty Land Act in 1850 allowed for veterans of the Mexican War (1846–1848) to obtain land warrants. Also in 1850, the U.S. Congress granted the state of Arkansas all swamp and overflow lands, many of which were in the region now included in Craighead County. The state recognized the potential value of the rich alluvial soil and immediately started draining the submerged land.

Many early settlers found their land grants under water and continued farther west until they came to the high ground of the ridge. Due to the regular flooding of the surrounding lowlands, the ridge was where most people preferred to live. The first real town in early Craighead County was Greensboro, located about eleven miles northeast of the present Jonesboro. It was settled in 1835 when a settler named Joe Willey cleared a town site and erected the county’s first gristmill.

On February 28, 1838, Governor Elias Nelson Conway approved an act that created Poinsett County in northeastern Arkansas from parts of Greene and St. Francis counties. Much of today’s Craighead County was included in the northern portion of Poinsett County, and its residents had to go a considerable distance to the Poinsett County seat in order to conduct their business. Running for the state legislature, William Jones made a campaign pledge to voters residing in the northern section of Poinsett County to use his influence to create a new county. After being elected, he proposed, in the 1858 legislative session, the creation of a new county in northeast Arkansas, offering to relinquish land in his own district of Poinsett County and suggesting that Greene and Mississippi counties do the same. “Crowley County” was originally proposed as the name of the new county.

The proposal called for the new county to incorporate land from the area represented by Jones’s fellow state senator, Thomas Craighead, who strongly opposed the idea. At a time when Craighead was allegedly absent from the Senate chamber (though some historians dispute this based on legislative records), the vote was taken, and the bill to create the new county was passed. The victorious Jones proposed that the county be named for Craighead—some say as a joke, others say as a gesture of goodwill. Craighead in turn proposed that the new county seat would be named for Jones, though some sources say it was named for Jones by its grateful citizens. Local farmer Fergus Snoddy donated fifteen acres of his land on the widest stretch of Crowley’s Ridge for a town site in the area that is now downtown Jonesboro.

Around the time of its formation, Craighead County included the communities of Big Creek, Broadway, Grinder, Buck Snort Hill, Martin’s Spring, Greensboro, Maumelle, Oldtown, and Lester Landing.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Following Arkansas’s secession from the Union in May 1861, several Confederate infantry companies were organized in Craighead County, though its population consisted mainly of small farmers and businessmen, not slaveholders on large plantations. The entire population of the county was just over 3,000 in 1860, with only eighty-seven enslaved people counted in that total.

The only reported military action fought in Craighead County was the August 3, 1862, Skirmish at Jonesboro in which several Union soldiers were killed, with an unreported number of Confederates dead. Bands of bushwhackers also roamed through the county.

The postwar Reconstruction was as harsh in Craighead County as it was in most other places throughout the defeated South. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) organized in the county with the ostensible goal of protecting property rights. Governor Powell Clayton placed Craighead County and several other Arkansas counties under martial law. In November 1868, he sent the state militia to Craighead County to clean out its Klan activity, much of which was centered around Greensboro. A confrontation took place between the Klan and militia at what was called Buck Snort Hill on the Greensboro Road. After some bloodshed and several arrests, the county sheriff offered immunity to any Klansmen who surrendered their guns. Many did, and the militia was withdrawn.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

A high incidence of courthouse fires in Jonesboro destroyed many of the county’s early documents. The original Craighead County Courthouse was a two-story frame building which was claimed by fire on February 14, 1869. A building just west of Court Square was used to conduct Craighead County’s business until 1876, when the county moved its records to a new wood-frame courthouse. Two years later, another fire destroyed that courthouse and its records, along with eight other businesses in Jonesboro. Yet another wooden courthouse burned on November 29, 1885, along with other downtown buildings around the square.

Since 1886, records have been kept in a vault, and no records have been lost since March 28, 1878. In 1886, a new courthouse was completed, this time made of brick and standing two stories tall. This building stood until 1934, when it was torn down to make room for the present main portion of the courthouse, which was dedicated on April 3, 1935. In 1883, a second Craighead County seat was established in Lake City, across the St. Francis River in the Buffalo Island area due to the long distances and difficult transportation involved in traveling between Jonesboro and the eastern part of the county.

Huge forests were located in Craighead County, with a variety of trees including oak, poplar, gum, pine, hickory, ash, and maple. On the lowlands, oak trees, cottonwood, cypress, hickory, and tupelo were abundant. The richness and variety of trees to be found in the county gave rise to a thriving lumber and woodworking industry in the late 1800s. The logs were for the most part hauled from the rural areas of the county to Jonesboro, where the lumber was processed and sent to market. One of the most significant events in the county’s history occurred in 1882 when the Cotton Belt railroad came through Jonesboro, bringing in people, goods, and building supplies and carrying lumber from the county’s timber industry to the rest of the nation.

The St. Francis Levee District was created on March 21, 1893. Prior to this time, the flood-prone Mississippi and St. Francis rivers often backed up to within sight of the town of Nettleton, just east of Jonesboro, with almost a solid sheet of water from there to the Mississippi. After land was drained east and west of Crowley’s Ridge, corn, cotton, potatoes, hay, and grains were grown.

The first of two known incidences of racial violence leading to lynchings took place in the county in 1881 when a white woman was killed during an apparent robbery of her home. Four African American men were arrested for the crime and reportedly confessed to two magistrates who ordered them held to be transported to jail in Jonesboro and to appear before a grand jury. On the night of March 12, a group of several hundred men took the four prisoners from the church where they were being held and hanged them. The second took place in 1920 when Wade Thomas was hanged from a telephone pole for the alleged killing of a Jonesboro police officer.

Early Twentieth Century

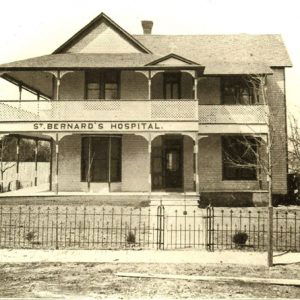

In 1900, a group of sisters from the Olivetan Benedictine order established a six-room hospital in Jonesboro called St. Bernard’s in honor of St. Bernard Tolomei, founder of the Olivetan Benedictines. In 1901, it expanded to accommodate its ever-increasing number of patients. Expansion of the hospital and associated health-related services has been almost continuous ever since, establishing Jonesboro and Craighead County as a regional medical hub.

In 1906, Jonesboro’s growth was enhanced with the creation of City Water & Light (CWL) as a municipal utility. CWL continues to serve the town and is often cited as a major factor in Jonesboro’s growth, attracting business and industry to the area due to its extremely reasonable utility rates.

Jonesboro also became the site of higher education institutions in Craighead County. In 1904, Woodland College was founded in Jonesboro, though it was forced to close in a few years for financial reasons, as did Jonesboro Baptist College, which was established in 1924. In 1909, the Arkansas legislature passed a law providing for state public schools of agriculture in each of the state’s four districts. Jonesboro was selected for one in great part because of its being a transportation center at that time, with sixteen passenger trains coming through Jonesboro daily. The school that was built eventually became Arkansas State College and is now Arkansas State University, a member of the Arkansas State University System headquartered in Little Rock (Pulaski County).

In 1910, a group of area farmers decided to try growing rice on the prairie lands in the western district of the county. Their success led to the creation in 1930 of what was at the time the largest rice mill in the world; it would become the second-largest with the completion of a larger mill in Stuttgart (Arkansas County), also operated by Riceland Foods, Inc.

Craighead County sent men to World War I soon after war was declared in 1917. Jonesboro’s “Company G” attracted men from around the county, while others volunteered for the navy. The first casualty from Craighead County was George W. Pickett of Jonesboro, where the American Legion post was named for him.

As early as 1920, while the rest of the country enjoyed postwar prosperity, Craighead County saw cotton prices rise and then slip from thirty-five cents to six cents. When prices rose, many Craighead County farmers bought more land on which to plant, often mortgaging their existing farms. The foreclosures of the Great Depression came early to Craighead County. With alternating drought, then flood, then drought again through the 1920s and 1930s, the heavily agricultural Craighead County struggled. Those who held on to their farms found no market for their crops, given the little money in the hands of consumers. County farm women, especially in the eastern district, often tried selling eggs in towns such as Monette but came back home at the end of the day after selling none. In the early 1930s, the Red Cross estimated that much of the county suffered from hunger. The Salvation Army agreed to care for the needy in Jonesboro, and the Red Cross cared for those in the rest of the county. After the Bank of Jonesboro was forced to close in 1931, the Bank of Nettleton and the Bank of Bono were the only ones operating in Craighead County until investors from St. Louis, Missouri, opened Mercantile Bank in Jonesboro in 1932.

The county became the site of fighting among various Baptist factions during the Jonesboro Church Wars in the early 1930s. The violence, which drew troops to the streets to try to keep the peace, led to at least one death and several injuries.

World War II through the Faubus Era

While county men and women again served their country in World War II, a new development occurred when U.S. Senator Hattie Caraway, a county resident, persuaded the Department of War to establish a College Training Detachment for the U.S. Army at Arkansas State College, bringing military men from all over the nation to Craighead County.

As the city of Jonesboro grew, it encompassed many former independent townships in the county. In 1958, Nettleton residents voted in favor of a proposed annexation to join the city of Jonesboro in order to receive city services such as police, fire protection, and city mail delivery, in addition to lower electric rates. The communities of Valley View and Westside were later also absorbed by Jonesboro.

Throughout the history of Craighead County, there was a sizable African–American community generally centered in Jonesboro, with enclaves engaged in agriculture throughout the surrounding county. “Uncle” Henry Allen, a former slave who came to the county at age thirteen, was a valuable historical resource for the black community in Craighead County until his death in 1940.

The most significant development for the black community was the belief in education by black parents, evidenced by the emergence of educational institutions such as a rickety structure for black elementary students on Jonesboro’s Cherry Street. Under the leadership of the black community, the Cherry Street School made way in the early 1900s for the segregated Craighead County–Jonesboro Training School, and in 1924 for Industrial High School (IHS), called Booker T. Washington High School (BTW) starting in 1935. It was the first high school for black students in northeast Arkansas and housed grades one through twelve. IHS/BTW attracted black students from all around the county. Students from outside Jonesboro either lived with relatives or boarded with the school’s principal, D. W. Hughes. By 1967, the integration of the county and Jonesboro public schools led to the demolition of Booker T. Washington High School. Pride in the institution still thrived, and even today, regular BTW reunions take place.

Jonesboro resident Francis Cherry became governor of Arkansas in 1953. After his single gubernatorial term in Little Rock, he worked for the U.S. Congress’s Subversive Activities Control Board before dying in 1965. Cherry is buried in Jonesboro.

Modern Era

Though Jonesboro remains the county’s center of business, industry, education, retail, and healthcare, Craighead County as a whole also produces bricks, chemicals, clothing, shoes, concrete, dairy products, feed, fertilizer, electric motors, furniture, and wood products, in addition to being active in agriculture and food processing. The county is home to recreational centers such as Craighead Forest and the Forrest L. Wood Crowley’s Ridge Nature Center. In the southeastern section of the county, the St. Francis Floodway offers opportunities for fishermen and duck hunters. Craighead County continues to be a growing and vibrant area of northeast Arkansas.

Craighead County is a dry county, meaning that alcoholic beverages cannot legally be sold. Bars flourished in Jonesboro through the World War II era. In 1944, however, while many local men were away in the service, a county-wide election voted Craighead County dry, outlawing the sale of alcoholic beverages within its borders. The county remains officially dry, though a number of establishments with “private club” privileges have been approved by the state.

In recent years, the combined employment needs of Jonesboro’s industries, St. Bernards Medical Center, and Arkansas State University have given rise to a number of “bedroom communities” with people commuting to Jonesboro from Bay, Bono, Brookland, and Lake City in Craighead County as well as Paragould (Greene County), Trumann (Poinsett County), and Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County). Outside of Jonesboro, the outlying towns in Craighead County remain largely agricultural.

The March on Religious Freedom took place in Jonesboro on August 1, 1993. Organized by members of the Wiccan/Pagan faiths, the march ended at the Craighead County Courthouse, Western District, where counter protestors engaged the marchers.

The county was the site of the Westside School Shooting in 1998, one of two ambush-style school shootings to take place in Arkansas that academic year.

Numerous athletes, authors, musicians, and artists are associated with the county. Olympic pole vaulter Earl Bell, Paralympic champion Grover Evans, and longtime coach and athletic director James Albert “Ike” Tomlinson all at one time resided in Craighead County. Playwright David Auburn, yodeler Carolina Cotton, author and photographer Norman Lavers, and artists Les Christensen and John Salvest all have ties to the county.

For additional information:

Craighead County, Arkansas. http://www.craigheadcounty.org/ (accessed August 11, 2023.)

Craighead County Historical Quarterly. Jonesboro: Craighead County Historical Society (1962–).

Education in Craighead County from 1900–1967: A Way Out for African-Americans. Video. Jonesboro: Rights in Education for Students and Parents, 2003.

McNamee, Heather. “Of Incendiary Origin: Interracial, Interclass, and Intraclass Intimidation and Violence in Craighead County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 81 (Autumn 2022): 282–292.

Morris, Jodi. “On High Ground: A Natural History of Crowley’s Ridge.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 44 (October 2006): 26–28.

———. “On High Ground: A Natural History of Crowley’s Ridge.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 45 (January 2007): 20–22.

Morrison, Edgar. “Big Bay.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 45 (January 2007): 23–27.

Stuck, Charles A. The Story of Craighead County: A Narrative of People and Events in Northeast Arkansas. Jonesboro, AR: 1960.

Veterans of Craighead County, Arkansas. Sikeston, MO: Acclaim Press, 2011.

Williams, Harry Lee. History of Craighead County, Arkansas. Little Rock: Parke-Harper Co., 1930.

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Henderson State University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.