calsfoundation@cals.org

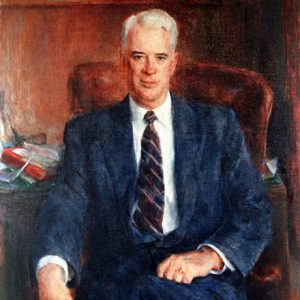

Francis Adams Cherry (1908–1965)

Thirty-fifth Governor (1953–1955)

Francis Adams Cherry was a chancery judge, Arkansas’s thirty-fifth governor, and chairman of the federal Subversive Activities Control Board. Cherry is most remembered for his political ineptness, which resulted in the election of Orval Faubus as governor in 1954.

Francis Cherry was born on September 5, 1908, in Fort Worth, Texas, to Haskille Scott and Clara Belle (Taylor) Cherry. The youngest of five children, he only briefly lived in Fort Worth before his father, a Rock Island Railroad conductor, was transferred. Cherry grew up in El Reno and Enid, Oklahoma, graduating from high school at the latter town. He majored in prelaw at Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Oklahoma State University) from 1926 to 1930. The Great Depression delayed his law school plans. After a series of odd jobs, he settled in 1932 in Fayetteville (Washington County) and entered law school at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville in 1933. There, he met Margaret Frierson, a native of Jonesboro (Craighead County) and the 1933 campus homecoming queen.

Cherry graduated in 1936. His first job out of law school was in the office of Leffel Gentry in Little Rock (Pulaski County). He married Frierson on November 10, 1937, and they then moved to Jonesboro, where he entered private practice with Marcus Feitz. He and his wife had three children. In 1939, Judge Thomas C. Trimble appointed him U.S. Commissioner for the Jonesboro Division of the Eastern District; in 1940, Governor Carl E. Bailey appointed him as a referee to the Workers’ Compensation Commission.

Cherry made his first try for elective office in 1942, when he ran for chancellor and probate judge of the Twelfth Chancery District. His father-in-law, Charles D. Frierson, was the first judge of this circuit. Cherry led in the Democratic primary and defeated incumbent John Frank Gautney in the runoff.

As a judge, Cherry was exempt from military call-up during World War II, but after his attempt to volunteer was thwarted, he applied directly to the Navy and received a commission as a lieutenant, junior grade. He served in the Judge Advocate General’s Corps in Washington DC. After two years, he returned to his judgeship in 1946. In 1948, Cherry was reelected without opposition.

Cherry entered the gubernatorial race in 1952; incumbent Sid McMath was seeking a third term. McMath had offended the state’s powerful utility company, Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L), and it spared no expense to tarnish his record. Cherry stood out because the other candidates were associated with discredited politics. Boyd Tackett, a former congressman whose district had been one of three the state lost following the 1950 census, attacked anyone with a foreign-sounding name; Jack Holt, the former attorney general, had many accumulated liabilities; and Attorney General Ike Murry was considered to be in AP&L’s pocket after his investigations of McMath and his campaign manager, Henry Woods. Cherry distanced himself from them by refusing donations over $500 and asking children to send him nickels and dimes. His was the only new face, and aligning himself with the decade’s anti-Communist fears and the non-partisan popularity of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the 1952 Republican presidential nominee, Cherry capitalized on his name—“Pick a Cherry”—and his apolitical honesty.

Cherry was unknown in the state. Following the advice of a Miami, Florida, advertising agency, Cherry spent his money on radio advertising. The “talk-a-thon” strategy, credited with ensuring Cherry’s win, worked for two reasons: first, most of the state had finally been electrified over the previous years, so almost all homes had radios; and second, television in the state was in its infancy. The strategy required Cherry to talk and answer questions for twenty-four and one half hours straight. His first talk-a-thon was on July 2, 1952; the twenty subsequent events were three hours each. He answered a total of 13,000 questions, the most common one being “Who is your barber?” The questioner could air a smear against another candidate, but Cherry was free to avoid answering. Polls showed the judge moving from last place to second. In the primary, Cherry finished 9,000 votes behind McMath, forcing an August 12 runoff that Cherry won by almost 100,000 votes. He trounced Republican Jefferson W. Speck in the general election.

In his inaugural address, Cherry spoke in glittering generalities about efficiency and economy. Rhetoric about his “Build Arkansas” program reflected nothing new over previous gubernatorial addresses. He opposed “taking money out of the states through taxes, taking it to Washington, then turning around and giving it back to the states.”

His most substantive proposal was the creation of a finance and administration department with broad fiscal powers. Adoption of the plan was assured when Cherry agreed to permit a legislative post-audit division. A second issue concerned highway commission reform. The Mack-Blackwell Amendment removed the commission from gubernatorial control, but local issues remained unsettled. Legislators wanted a special session largely to regain some control over the commission, but Cherry did not oblige.

From the start, it was apparent that Cherry and his chief of staff, Leffel Gentry, were not adept at politics. First, he made two appointments from out of state; probably nothing offended legislators more than hiring “foreigners.” Second, in the early 1950s, as agricultural machines replaced people in the Delta, the population flight of the previous decade continued, and a severe drought hit row-crop and cattle farmers hard. Cherry vetoed a sales tax exemption for feed, seed, and fertilizer. Third, AP&L raised rates. The sentiment was that this corporate decision would not have been made if Cherry had strongly opposed it.

Orval Faubus denied Cherry the incumbent’s customary second term. Faubus, a little-known highway commissioner with strong ties to the GI movement and McMath, had become owner of the Madison County Record. Faubus’s presence was important enough to be noted by the press when he attended Cherry’s inaugural address.

Faubus wanted to oppose Cherry in 1954, but kingmaker Witt Stephens, whose off-Wall Street brokerage firm had virtually monopolized marketing Arkansas bond issues, told Faubus that if he ran, his friend Congressman James W. Trimble would find himself in trouble. In a famous comment during a visit to Little Rock, Faubus told the press he would not announce his candidacy “at this time.” But announce he did, just before the deadline and too late for Stephens to field a candidate against Trimble.

The race was simultaneous with McMath’s attempt to defeat Senator John McClellan. On the gubernatorial side, Boyce Drummond said, few races “generated such a high degree of voter interest or fell victim to such low standards of ethics.” Issues included Cherry’s punitive attitude toward welfare recipients; 2,300 “deadheads,” as the governor called them, were dropped from the rolls before the election. A photo opportunity was handed Faubus when the state sold the Confederate home for the bauxite that lay underneath it and moved the residents—all females—to Camp Joseph T. Robinson, where blame for the subsequent high death rate landed on Cherry. Faubus and three other candidates, including the always-controversial state senator from Conway (Faulkner County), Guy “Mutt” Jones, denied Cherry a majority in the primary.

In the runoff that followed, Faubus took note of the newly announced U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954) by saying any sudden integration would disturb the state’s allegedly harmonious race relations. Cherry had been silent on this subject. Several journalists, most from out of state, had raised this issue but received non-committal responses from his office.

The dominant issue in the runoff was Cherry’s unearthing the charge that Faubus had attended Commonwealth College near Mena (Polk County), a labor school with communist leanings. While the allegation was true, in the context of the political witch-hunt being run by Republican Senator Joe McCarthy, Cherry’s raising the issue amounted to a “red herring.” Faubus at first tried to deny the charge but, in a carefully orchestrated television appearance, admitted attending, although he denied he had stayed at the school once he understood what it stood for. He then played on his rural roots and his desire—at any cost—for an education.

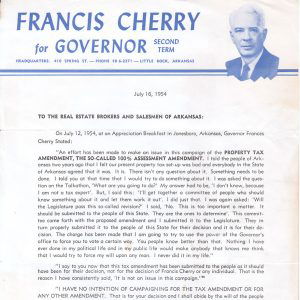

Cherry himself administered the coup de grace. He threw all his support behind a constitutional amendment to equalize property tax assessments. “I would rather see this tax provision go through than be governor of Arkansas,” he said. Opponents said uniform reassessment was a plot to raise taxes, and Cherry, who had started out so confidently in the fight, then abruptly turned his back on the issue, saying it remained “up to the people now.” Cherry had little support in the legislature. Unwilling to play its games, he even instructed agency heads to avoid politics. Faubus almost doubled his totals in the runoff.

Cherry’s defeat was followed by the failure of the property tax amendment in the general election. Since the adoption of the 1874 constitution, only Tom Terral (1925–1927) had been denied a second two-year term. And like Terral, Cherry had blundered on the side of honesty. Interestingly for the future of the state Republican Party, many disaffected Cherry supporters cast votes in November for Pratt C. Remmel, the Republican nominee, whose total vote tripled that of Speck two years before.

Cherry moved to Washington DC in 1955. “I would do it exactly the same,” he told a reporter in a 1964 visit. His botched exposure of Faubus may have led to a federal job—as a member of the Subversive Activities Control Board, the federal body charged by Congress with running down communists. McClellan probably orchestrated the appointment with Eisenhower, but Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson renewed it; Kennedy named Cherry board chairman.

Cherry developed heart trouble, undergoing surgery in 1963; he died two years later on July 15, 1965. His body lay in state in the rotunda of the Arkansas State Capitol before a service in Jonesboro and interment in Oaklawn Cemetery in Jonesboro. He was survived by his wife and three children: Haskille Scott III, Charlotte, and Francis Jr.

For additional information:

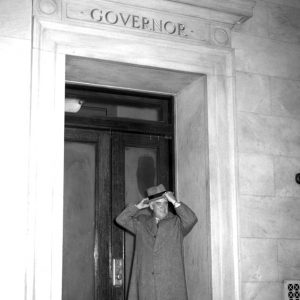

“Cherry Takes Over as Governor.” Arkansas Gazette. January 14, 1953, p. 1A.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Drummond, Boyce. “Arkansas, 1940–1954.” In Historical Report of the Secretary of State (Arkansas), 1978. Little Rock: Secretary of State, 1978.

“Francis A. Cherry, Governor in ’53–55, Dies at Washington.” Arkansas Gazette. July 16, 1965, p. 1A.

Francis Cherry Papers. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Francis Cherry Papers. Dean B. Ellis Library Archives and Special Collections. Arkansas State University, Jonesboro, Arkansas.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Francis Cherry

Francis Cherry  Francis Cherry and family

Francis Cherry and family  Francis Cherry

Francis Cherry  Francis Cherry

Francis Cherry  Cherry Ribbon

Cherry Ribbon  Cherry at Capitol

Cherry at Capitol  Cherry Campaign Letter

Cherry Campaign Letter  Francis and Margaret Cherry

Francis and Margaret Cherry  Francis Cherry House

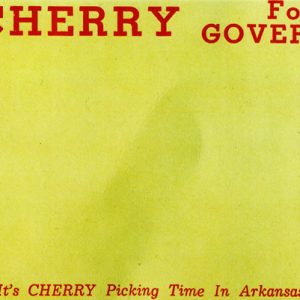

Francis Cherry House  Cherry Campaign Flyer

Cherry Campaign Flyer  Francis Cherry Campaign Postcard

Francis Cherry Campaign Postcard

I have no idea why, but I dreamed of Governor “One Way Cherry” last night. Having grown up in Blytheville and Paragould, I heard that Governor Cherry got that nickname as a result of the highway construction budget being insufficient to pave the highways that were planned, so Governor Cherry was responsible for the decision to pave half the highway. According to my elder(s) telling the story, people would drive on the paved half of the highway no matter which way they were going until there was traffic in both directions. Then, the person who was supposed to be on the unpaved side had to move back over and stay there until it was safe to get back on the paved side once again. When I got up this morning, I did an Internet search, which is how I came up with your website. I’m just curious as to the accuracy of the story I was told. [Editor’s note: We don’t know if it is accurate either, but it is a great story!]