calsfoundation@cals.org

GI Revolt

The political reform movement known as the GI Revolt emerged during the county political campaigns of 1946. Typically associated with World War II veterans eager to bring change to their hometowns and the state of Arkansas, the movement actually was broader than just military service veterans and had a limited statewide impact.

The term “GI” was shorthand for “Government Improvement” (a play on the term GI—General Issue, i.e., enlisted men—because many involved in the movement were returning GIs and officers), which had an identifiable organization in six counties: Cleveland, Crittenden, Garland, Montgomery, Pope, and Yell, as well as the city of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). While government improvement citizen groups had organized before and continue to appear until the present, the revolt in question was a product of the campaigns of 1946 and the immediate follow-up to those.

Most attention on the GI Revolt has focused on Hot Springs (Garland County) and Garland County. There, hometown war hero Sidney Sanders (Sid) McMath organized fellow World War II veterans to challenge the political leadership of Mayor Leo P. McLaughlin and key city and county elected officials. McMath graduated from high school in Hot Springs where he had observed firsthand how the McLaughlin organization controlled almost every aspect of the city and county. After World War II, he took up a pledge he had made to himself as a teenager—to challenge the political leadership of the spa city. In 1946, McMath filed in the Democratic Party primary for prosecuting attorney of the Eighteenth Judicial District, which included Garland and Montgomery counties, and recruited fellow veteran Clyde Brown to file for district judge with jurisdiction over the same two counties. Before the filing period closed, the two GIs had succeeded in recruiting candidates for each of the elected offices. However, while the “reformers” shared a common interest in defeating the entrenched incumbents, they were not ideologically united. Some wanted to abolish gambling, while others did not. Most were war veterans, but some were not. And some had been interested in seeking public office long before the GI Revolt was organized and used the new anti-establishment group as a means to advance their ambitions.

The call for reform in Hot Springs was based in part on two official reports. The first came from a 1942 federal grand jury report that found that Garland County election officials had ignored and/or violated most of the state’s election laws in the elections of that year. Another grand jury report released while the 1946 primary campaign was in progress noted that graft and corruption had permeated the public school system, as well as the business, religious, and social activities in the city. Citing these abuses as evidence of a clear need for reform, the GIs used their military training to organize every voting precinct in Garland and Montgomery counties, working in pairs to reduce possible harassment from the opposition.

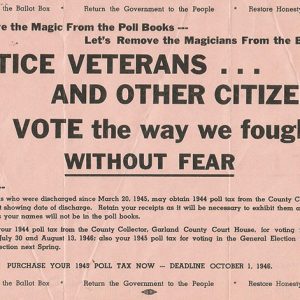

A number of other counties had earned a reputation as “machine counties,” which meant the political offices were controlled by selected individuals who used a variety of tactics to gain and maintain office. Key among the “control” devices was the poll tax receipt. The Election Law of 1891 required that, to be eligible to vote in a party primary, one must show evidence of having paid a poll tax. For the general election in November, voters could pay their poll tax up to twenty days before the election. Maintaining records for two different years presented an opportunity for graft. Savvy politicians had learned to monitor the tax records and pay the poll tax for those citizens who failed to meet the deadline. Unless challenged, any individual could vote simply by showing the poll tax receipt and signing the election register. It was not uncommon in many counties for a single individual to cast multiple votes as proxies using poll tax receipts. To challenge a vote’s legitimacy, the challenger was required to file a petition and present evidence of fraud with a state court—or federal court if the dispute involved a candidate for federal office.

In Garland County, McLaughlin and his allies used the poll tax as a way to defeat everyone on the GI ticket except McMath in the Democratic primary. Believing that their defeat had been engineered by fraudulent use of poll tax receipts, the GIs filed as independent candidates to run in the November general election. Included on the ticket was Pat Mullis—not a veteran but a friend and law school classmate of McMath—who filed for the Fourth Congressional District position. Mullis then filed a lawsuit in Arkansas Western District Court on behalf of his fellow “independents,” claiming poll tax receipts had been illegally issued and used.

While collecting evidence for the trial, GI supporters found that in every city ward, poll tax receipts had been issued in alphabetical order, six, twelve, or eighteen names to a block. Moreover, the signatures for each block of names appeared to be in the handwriting of a single individual. Judge John Miller heard the case without a jury and ruled in favor of the GIs. He noted in part that individuals organizing in alphabetical order and presenting themselves to the County Clerk to pay their poll tax was a statistical improbability. Also, the testimony of an expert witness from the Kansas Bureau of Investigation saying that the signatures were in the same handwriting was sufficient proof to allow Judge Miller to issue an order setting aside almost twenty-four percent of the poll tax receipts issued for the primary election.

Motivated by their court victory, the GI independents mounted an aggressive campaign for the general election. Organizing a new “poll tax drive,” they encouraged citizens to pay their own poll tax and be prepared to vote in November. Their efforts were rewarded in spectacular fashion. When the final results were tabulated, the GI ticket had won every seat in Garland County.

Results from the GI tickets in the other five counties were not so clearly delineated. While a number of war veterans campaigning as reform candidates did get elected to public office in 1946, there was no definable pattern to their success, and as was the tradition in Arkansas politics, the personality of the candidate and local circumstances typically determined election outcomes. Moreover, in Garland County in particular, almost half of the candidates elected on the GI ticket in 1946 were themselves criticized for using public office for personal gain within a decade after their initial election. McMath tried, with some success, to extend his good government influence beyond Hot Springs by inviting fellow GIs to join the Young Democrats organization. He also used the publicity he gained from challenging the McLaughlin organization to launch a successful campaign for governor in 1948. As the state’s chief executive, McMath moved away from local government improvement issues and focused more on matters of statewide interest.

By 1950, the GI Revolt was in disarray. Organized initially to work for “honest government,” the leadership failed to develop a broad-based agenda and was unable to negate the corruptive practices of the poll tax. Arkansas’s more than 200,000 World War II veterans were never able to become a cohesive unit. While most had either witnessed first hand, or at least been informed of, the totalitarian practices of Germany, Italy, and Japan, few related those practices to their own counties and hometowns. Moreover, during the 1950s and 1960s, new “McLaughlin-like” organizations sprang up in various parts of the state. It was not until the Twenty-fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolished the poll tax in federal elections that a measure of political reform was restored in the state. The GI Revolt lacked sufficient clarity on what constituted good government and was too localized to be considered a real revolt.

For additional information:

Abbott, Shirley. The Bookmaker’s Daughter: A Memory Unbound. New York: Ticknor and Fields, 1991.

Blair, Diane D., and Jay Barth. Arkansas Politics and Government: Do the People Rule? 2nd ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Johnson, Ben F. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Lester, James. A Man for Arkansas: Sid McMath and the Southern Reform Tradition. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1976.

McMath, Sidney S. Promises Kept: A Memoir. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Ramsey, Patsy Hawthorn. “A Place at the Table: Hot Springs and the GI Revolt.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Winter 2000): 407–428.

C. Fred Williams

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.