calsfoundation@cals.org

Photography

Photography reached the Arkansas frontier in 1842, three years after the invention was announced to the world in Paris, France. For the first fifty years or so, photography as a science and an art was in flux; photographic processes changed, photographers moved to and from Arkansas, and many early practitioners remain unknown. Photographs were made on metal, glass, leather, and wood. Eventually, the collodion wet-plate process, in combination with albumen-coated photographic papers, became the process of choice, and photographers began to expand their interest beyond the portrait to other subject matter. Early photographers were versatile and adaptable, and their photographs played a strong role in preserving the cultural and historical heritage of Arkansas.

Photography is defined as the act of arresting an image, usually formed in the camera obscura (from the Latin meaning “darkened chamber,” now simply called a camera), and rendering it permanent through chemical or electronic means. Photography has become an extension of the eye and of the visual world and an invaluable aid to memory. The invention of photography was announced to the public in France on August 19, 1839. The invention was received around the world with unusual enthusiasm.

Photographer C. P. Moore, the first to photograph Native Americans west of the Mississippi River, offered his services in Arkansas in June 1842. Moore, from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, had already visited Van Buren (Crawford County), as well as Fort Gibson and the Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), before establishing himself at the Anthony House, a hotel in the heart of downtown Little Rock (Pulaski County). Before the year was out, he sold his photographic equipment to doctor A. M. Dignowity. Photographers were itinerants and tended to stay in one place no longer than five years. After exhausting their market in one location, they moved on.

Arkansas was a rural frontier state, and photographers often had multiple occupations in order to make a living. They were teachers, shopkeepers, blacksmiths, clockmakers, and jewelers in addition to being photographers. For example, a daguerreotypist from Helena (Phillips County) was a teacher, an imitator of fancy woods and marble, as well as a decorative and plain paperhanger. In addition to making a likeness, this photographer could also decorate houses for wealthy clients.

Early photographers in Arkansas were adaptable; they took “rooms” in populated areas in hotels, stores, banks, and even courthouses. While they generally worked indoors, photographers needed direct sunlight to make their exposures. For this reason, studios were often situated on the second floor of buildings that could be outfitted with a skylight. Normally, three rooms were required: a gallery/waiting/reception room, a camera room, and a processing and finishing room. In addition to stationary locations, studios and living quarters were set up in almost anything that could be moved, such as wagons, river boats, and railway cars.

Even more photographers appeared in the wake of wars, the California gold rush, federal geological surveys, the building of transcontinental railways, and with each new improvement in the photographic process. Thomas W. Bankes of Helena became a photographer and followed General Frederick Steele’s army to Little Rock. He, along with A. J. Millard and R. H. White, was responsible for several early views of the city and of army infrastructure during the Federal occupation from 1863 to 1865.

The first photographic process was called the daguerreotype after its inventor, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, a French painter and inventor of the diorama. The process involved a highly buffed silvered copper sheet sensitized with iodine vapor. After exposure to light, in the camera obscura, the plate was developed in mercury fumes, fixed, and washed. The result was a silvery, mirror-like image protected with a glass cover and placed in a special case made of papier maché, stamped paper, or tooled leather. Plate sizes varied and were described in fractions from one-ninth to double whole plate. The one-quarter plate, 3 ¼ x 4 ¼ inches, was the conventional size. Rarely were any plates larger than the double whole plate 8 ½ x 13 inches or smaller than 1 ¾ x 1 ½ inches.

While daguerreotypists photographed exotic landmarks, great architectural monuments, and even the moon, most photographers gave their attention to making portraits. A popular admonition was “secure the shadow ere the substance fade” (get one’s portrait made now before turning into dust). Previous to photography, painters of miniatures made portraits for keepsakes. It was a tedious and expensive process and sometimes untruthfully flattering. Not so with early photographs; many advertisements claimed that photographs were faithful to nature and therefore were truthful.

The next major photographic process in America involved collodion, a clear viscous material made of gun cotton dissolved in ether and alcohol. It was used as a medium to bind light-sensitive materials to glass. Collodion appeared in three guises: the ambrotype, tintype, and the wet-plate process. When under-exposed, collodion negatives were viewed by reflected light against a dark ground, and the appearance was that of a positive. This observed phenomenon was the basis for the ambrotype and tintype. An ambrotype was made by flowing sensitized collodion over clear or ruby red glass, exposing the plate in the camera, developing the image, and finally by fixing and washing it. The resulting negative was protected by clear glass, backed by black paper or velvet, and stored in a case like the daguerreotype. Plate sizes were similar to daguerreotypes. The image, however, was not considered as fine as a daguerreotype, but it was faster, less expensive to produce and acquire, and therefore popular.

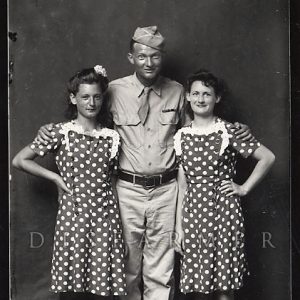

The tintype consisted of sensitized collodion over a japanned black sheet of iron and was uniquely American. While tintypes provided one-of-a-kind portraits, cameras with multiple lenses made several images “at a pop” possible. After processing, the sheet was cut up into single portraits that were presented to customers in paper folders with a cut-out frame. Unlike the daguerreotype and ambrotype, the tintype was rugged; it could be carried about and even mailed. It was very popular during the Civil War. Tintypes fueled the craze for family albums.

The wet-plate process consisted of flowing iodized collodion over glass, sensitizing it with silver nitrate and (while still wet, before it lost sensitivity to light) exposing it in the camera, then developing, fixing, and washing it. The glass negative and paper positive approach enabled multiple copies of an image to be made inexpensively and easily. The wet-plate process enabled millions of portraits to be made on paper. The most common form was the carte de visite (a French term for a calling card). Prints from glass negatives were cut up and mounted on cards measuring 4 x 2 ½ inches. The cards were usually imprinted on the back with the photographer’s name and studio address. The wet-plate process enabled professional photographers to move out of their studios even though it was a difficult process to manage in the field.

Early advertisements indicate that many processes were offered concurrently; photographers were versatile and could guarantee photographs in the “latest approved style with complete satisfaction.” By the late nineteenth century, with the introduction of the box camera and gelatin-silver roll film, photography became ever more accessible. Professional photographers distinguished themselves from the rising class of amateurs by continuing to master large, factory-prepared dry plate negatives on glass for contact printing and easy retouching capabilities.

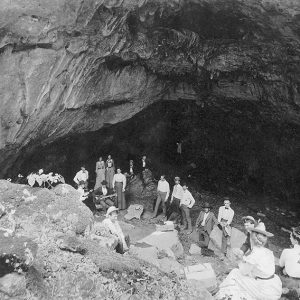

By the end of the nineteenth century, images of many prominent landmarks, monuments, and organizations appear, such as courthouses, churches, gravesites and memorials, congregations, and fraternal and political organizations. With tourism and the expansion of railroads in the state, photographs of spas appeared as well. A number of photographers in Hot Springs (Garland County) photographed the bathhouses and family gatherings at Happy Hollow amusement park.

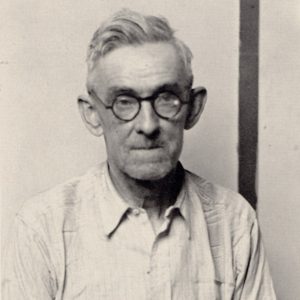

A period of particular interest occurred during the Great Depression. In the mid-1930s, the federal government endeavored to record the appalling rural conditions caused by economic upheaval as a tool for convincing the public of the need for government programs. Many other nationally known photographers—including Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Jack Delano, Andreas Feininger, Russell Lee, and Carl Mydams—traveled through Arkansas documenting rural conditions and the projects of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. One Arkansas photographer who made his mark during the Great Depression and World War II was Mike Meyer, known more popularly by the name of Mike Disfarmer.

In 1957, Arkansas native Will Counts was among many photojournalists covering the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock. The Arkansas Democrat nominated his work for the Pulitzer Prize, though he lost out to other competitors. Counts went on to have a distinguished career in photojournalism. Many of his Central High School photographs are in the collection of the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts.

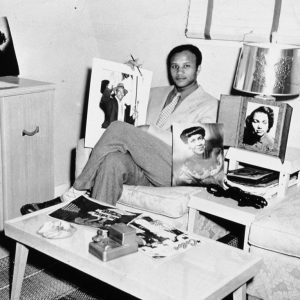

The second half of the twentieth century produced a number of notable Arkansas photographers, including Tom Harding III (1911–2002), Greer Lyle (1925–), and William E. Davis (1918–). All three were successful commercial photographers whose careers began after World War II. Harding was a portrait photographer who mastered the pinhole camera and the art of making platinum prints. Lyle, a portrait photographer, was an avid photo historian and an inspiring leader of the Arkansas Professional Photographers Association, which was founded in 1941 and remains active today. Davis was a commercial photographer with major advertising accounts before retiring and coming under the influence of West Coast photographers.

Among the Arkansas photographers of note whose work continues in the twenty-first century are Tim Ernst (1955–), Tim Hursley (1955–), and Michael Schultz (1952–). Ernst is a wilderness photographer who has produced numerous books on Arkansas hiking trails, flora, and fauna. Hursley, who lives in Little Rock, specializes in architectural photography. Schultz is an independent photographer whose specialty is digitally photographing large industrial complexes and foundries. He was a recipient of a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship and an Arkansas Arts Council Artist Fellowship Award in 2010.

Over the course of photography’s history, most photographers brought their skills with them. They learned from other photographers, and occasionally they apprenticed under an experienced photographer. In addition the photographic supply, companies like Kodak kept men available in the field; they were a great help to the professional photographer. Professional schools of photography were located out of state as well. Davis received his professional training in Texas. Harding is self-taught, having learned much while in the U.S. Army and apprenticing in New York. Today, it is possible to study photography at several state universities and colleges, in either fine arts or journalism departments.

For additional information:

Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, Little Rock, Arkansas. https://www.arkmfa.org/ (accessed February 7, 2022).

Bennett, Swannee, and William B. Worthen. Made in Arkansas, Vol. 2: Photography and Art. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991

“Early Photography in Northwest Arkansas.” Springdale, AR: Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, n.d.

Hunter, Marjorie Jo. “Hope and Despair: The Farm Security Administration Photographs in Eastern Arkansas during the Great Depression.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2012.

Lyle, Greer. Have I Ever Told You. Little Rock: 1994.

Taft, Robert. Photography and the American Scene. New York: Dover Publications, 1938.

Alan Du Bois

Benton, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.