calsfoundation@cals.org

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Arkansas faced a number of opportunities and challenges in the first four decades of the twentieth century. Not only did the state introduce some significant initiatives in response to the multi-faceted reform movement known as progressivism, it also endured race riots, natural disasters, and severe economic problems. Even as it attempted to modernize its road and school systems, expand its manufacturing sector, and deal with increasing urbanization, most Arkansans continued to live in rural areas and remained largely conservative, both in their attitudes toward traditional social relations, particularly with regard to race, and in their religious orthodoxy. The tension between the need to modernize and the provincialism of rural Arkansas persisted throughout the era and inhibited meaningful change. Although the Great Depression and the New Deal undermined the old system by introducing a new player in the field—the federal government—and provided a forum by which certain groups in Arkansas could dare to challenge elites, political power remained with those who traditionally ruled, and even divisions within that group did not work to the advantage of these newly assertive voices. Given the limitations of reform and the challenges of the Great Depression, the state was hardly poised to take advantage of the opportunities of the wartime economy that was on the horizon in 1940.

Progressivism

The seeds of at least some “progressive” reforms were planted in Arkansas during the nineteenth century: prohibition of liquor and women’s suffrage. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) opened a chapter in Arkansas in 1879, and women from all corners of the state began to agitate against “demon rum.” They adopted the strategy of local option, which involved allowing voters in distinct localities to decide on whether the sale of liquor would be permitted. They were joined in 1886 by the Arkansas Prohibition Alliance, an organization that excluded female members and, by 1912, were using another progressive measure, the initiative, in an attempt to achieve their ultimate goal: a statewide ban against the sale of alcohol. Arkansas voters in 1910 had approved a constitutional amendment validating the use of the initiative and referendum. The former provided the electorate with a greater role to play in initiating laws; the latter could reject laws passed by the legislature with which the electorate did not agree. Under the provisions of the initiative, voters in 1912 circulated petitions to place a prohibition measure on a ballot but failed to secure enough votes for passage. Prohibitionists turned their attention to the legislature and successfully pressured it to pass the Newberry Act in 1915, which effectively banned the manufacture and sale of alcohol in the state, followed by the “Bone Dry” law in 1917.

Women had played an important role in the fight for prohibition, but they had been seriously hampered by their inability to vote. In the 1880s and 1890s, some women’s magazines and clubs championed enfranchisement, but other women’s organizations refrained from openly supporting voting rights for women. Women’s book clubs, which began to proliferate in communities throughout the state, typically confined themselves to promoting literacy and libraries, but other women became activists of a sort. The WCTU, for example, was heavily peopled by church women who had first developed a taste for activism through their association with organizations sponsored by their churches. For some women, it was a short step from the fight against demon rum to the struggle for voting rights. The suffrage movement gained an important ally with the election of Governor Charles Brough in 1916. His wife, Anne, was dedicated to the issue and, with her husband, helped convince the Arkansas General Assembly in 1917 to allow women to vote in primary elections. Arkansas subsequently became the second state in the South to ratify the nineteenth amendment in 1920.

Another progressive reform that had roots in the nineteenth century involved the end of the convict leasing system. Arkansas used convict leasing as a revenue-generating measure, but prisoners were often kept in horrible conditions, and Arkansas governors began to agitate for its abolition in the 1880s. By the turn of the century, the situation was approaching a national scandal, and in 1912, Governor George Washington Donaghey, who had been unable to convince the legislature to act, simply furloughed 360 prisoners from prison, thus making it impossible to furnish enough prisoners to honor convict leasing contracts. That effectively ended the system in Arkansas.

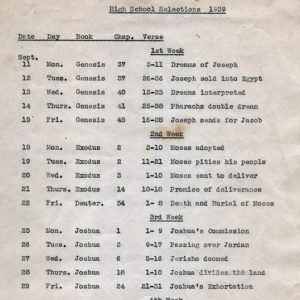

A Crisis in Education

Progressives were concerned about Arkansas’s educational system, but the desire for improvements to education extended beyond the Progressive Era. The under-funded public school system, which itself was only a few decades old, became the preoccupation of those who sought to expand literacy in the state. In 1900, Arkansas schools ranked among the worst in the country in all indices: school attendance, length of school term, per pupil expenditure, ratio of students to teachers, and educational level of teachers. In addition, the total number of school districts in the state far exceeded a level the state could support. In 1900, there were 4,903; by 1920, there were 5,118. Efforts to reform the system began in the early twentieth century and met with some success in the decades that followed: the creation of a new state board of education and a literacy commission, increased support for high school education, enactment of a compulsory attendance law, and the founding of local and county boards of education. Despite these improvements, a federal survey conducted in 1921–1922 concluded that Arkansas’s children received an education that put them at a distinct disadvantage in the modern world.

An intractable problem was devising a strategy that would adequately fund the state’s schools. The revenue generated from property taxes in rural areas was vastly insufficient, and a different tax structure had to be devised, one that shifted the burden away from the rural areas and required citizens in towns and cities to share the burden of educating all the state’s children. The legislature responded to pressure by passing a severance tax with all proceeds accruing to public education, but an income tax, and later a tobacco tax, also earmarked for education, were declared unconstitutional. The legislature subsequently restructured the tobacco tax in a way that passed muster with the Arkansas Supreme Court. In 1929, the legislature enacted the Hall Net Income Tax Law, which established a system of equitable taxation on incomes, a system of taxation that did not place most of the burden on rural Arkansans. Some rural schools were consolidated, a school bus system was inaugurated, and the school term was lengthened. But the Great Depression ended reform, and by the early 1930s, many teachers were accepting worthless county scrip as payment for their services. A new crisis in education faced Junius Marion Futrell, who was elected to governor in 1932.

Futrell, who believed that anything beyond an eighth grade education should be reserved for the privileged few, set about enacting his campaign pledge: retrenchment, and for him, this meant a reduction in state expenditures. He became embroiled in a controversy with the federal government when he used Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) funds to pay teacher salaries. When Harry Hopkins, director of FERA, threatened to cease funding all federal programs in Arkansas, including the farm program of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), something close to the hearts of the politically powerful eastern Arkansas planters, Futrell ultimately called for the repeal of prohibition so liquor sales could be taxed. He also supported the legalization of gambling, which provided for the opening of a dog track in West Memphis (Crittenden County) and a horse-racing track in Hot Springs (Garland County), both of which would be subject to taxation. He later endorsed a tax on retail sales. The school funding problem had been solved, at least for a time.

Transportation

Improved transportation was another effort to modernize the state that nearly collapsed in the face of the Great Depression. The construction of roads had always been the province of local governments, and this had worked reasonably well until the advent of the automobile, which demanded a much more comprehensive system of roads and the construction of roads that would tolerate automobile traffic. The state complicated the situation by passing a law in 1907 that allowed counties to create road improvement districts, sell bonds to pay for the construction of the roads, and then tax the citizens who were to benefit. This seemed like a logical way to proceed, but in fact, it led to the problem of poorly coordinated and unsupervised construction. Acting without supervision or coordination, many counties constructed roads that were inadequate or simply ended at the county line. Still, the state attempted to adapt to the evolving situation, requiring automobile drivers to purchase licenses in 1911 and creating a state highway commission in 1913. The commission, however, had little control over the widely scattered road improvement districts, and the passage of the Alexander Road Improvement law in 1913 further intensified the localized nature of road construction.

Although the state was able to qualify for federal aid to roads in 1917, by 1921, the road system was in such disarray that its ability to qualify for matching funds in a federal roads program was in question. In order to participate in the program, the state needed to abolish the road improvement districts and centralize road construction in the Arkansas Department of Transportation. When the legislature balked, federal funds were withdrawn, and the improvement districts faced bankruptcy. Only then did the legislature pass the Harrelson Road Act in October 1923, giving the highway commission supervisory responsibility. However, the separate road districts continued to exist, and the commission exercised little significant influence. By 1927, the county road districts were either bankrupt or close to it. Governor John E. Martineau secured legislation that allowed the state to assume the debts and responsibilities of the road improvement districts and launched the Martineau Road Plan, an ambitious state highway construction program. His successor in office, Harvey Parnell, secured passage of legislation authorizing $18 million in bonds to continue the expansion of the Martineau Road Plan, and additional legislation permitted the sale of $7.5 million in bonds to finance a highway toll-bridge construction program. However, Parnell’s ambitious plans for expansion of the highway system in Arkansas were largely undermined by the deteriorating economic situation and the drought of 1930–1931.

By 1933, the state’s highway debt reached a staggering $146,000,000, and Gov. Marion Futrell devised a strategy for refunding the highway debt. To consolidate all the highway debts into one, he called a special session in 1934 and pushed his Highway Refunding Act through. The highway debt problem had been temporarily solved.

Crisis in Agriculture

Agriculture, which dominated the state’s economy at the beginning of the century and continued to do so throughout the era, was also saved by New Deal programs. Although it was not the sector of the economy that New South advocates of the late nineteenth century championed, it was the one that expanded most dramatically in the twentieth century. In fact, most of the limited expansion in the manufacturing sector came as a result of the processing of agricultural or timber products. From apple orchards in the northwest to the cotton plantations of the Delta, agriculture fed the manufacturing sector. The orchard industry in the state, however, fell victim to a blight in the 1920s, and the cotton economy nearly crumbled under the burden of a precipitous decline in cotton prices following World War I.

As historian Carl Moneyhon suggests, the most significant problem was that too many people were trying to make a living on too few farms. Between 1900 and 1930, the number of farmers in Arkansas increased from 178,694 to 242,334, while the acres in farms actually decreased slightly, from 16,636,719 in 1900 to 16,052,962 in 1930. This statewide total masked a trend occurring in the Delta, where an expansion of the plantation system was transforming the landscape. With the advent of railroads in the late nineteenth century and the emergence of the lumber industry in many previously overlooked Delta counties, the plantation system supplanted forests and swamps. One particularly striking index of the plantation’s arrival was the increase in tenancy. During a period when the number of farmers had increased significantly, the number of farm owners remained almost steady, from 84,138 in 1900 to 85,842 in 1940. The number of share tenants increased in that period from 53,837 to 83,835.

The particularly loathsome systems of tenancy and sharecropping placed an extraordinary burden of debt upon those least able to support it. Although both are forms of tenancy, the common vernacular characterized them as sharecropping or tenancy. In the sharecropping arrangement, a man without implements and mules secured a contract, typically a verbal one, with a land owner. The sharecropper was provided mules, implements, a place to live, and advances from the land owner’s commissary. At the end of the year, the planter paid the sharecropper about one third of the cotton crop in exchange for his labors. Given the high interest rates at the company store, many sharecroppers found themselves owing the planter at the end of the year. The tenant farmer was only marginally better off. He brought more to the bargaining table—mules and implements—but he, too, lived in a house owned by the planter and secured advances from the company store. Although he received half of the cotton crop in exchange for his labor, he often found himself in debt at the end of the year.

Racial Turmoil

The burden of sharecropping and tenancy fell heaviest on the Black population, a population that endured a series of significant setbacks beginning with the passage of disfranchisement and segregation statutes in the 1890s. By the late nineteenth century, disfranchisement had come to be accepted as a political reform. In fact, it served to shore up a faltering Democratic Party lock on the electoral process. The 1880s and 1890s had witnessed an electoral challenge from a third party that seemed likely to unite poor white and Black voters. By the passage of the Election Law of 1891 and a subsequent poll tax, large numbers of illiterate and poor Black (and white) voters were eliminated from the electoral process. The secret ballot required that illiterate voters have election judges, rather than friends, mark their ballots. The poll tax imposed a financial burden upon the poorest segment of the population and, together with the prohibitions affecting illiterates, effectively disfranchised eighteen percent of Black voters and seven percent of white voters. The final instrument of disfranchisement enacted in Arkansas was the White Primary. In 1906, the state Democratic Party, like that in other Southern states, voted to allow only white voters the right to participate in the Democratic primary. One founding member of the Little Rock (Pulaski County) chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Dr. John M. Robinson, was not content to suffer disfranchisement and, in 1928, launched the Arkansas Negro Democratic Organization. He filed suit in Arkansas against the White Primary but was disappointed when the Arkansas Supreme Court upheld the white-only Democratic primary in Robinson v. Holman.

Arkansas’s Black population faced other challenges. As the plantation sector expanded and both Black and white immigrants from other Southern states came to Arkansas to work the land, competition arose between them for plantation jobs. Planters often preferred Black labor because they could legally pay them less and work them harder. Impoverished, segregated (isolated), and disfranchised, they made easy targets. A number of nightriding incidences occurred, with the object being to drive Black farmers from the plantations so that whites could secure their positions. Two cases involving twenty-seven defendants were prosecuted in federal court in 1904, but only in one were convictions secured. The case, Hodges v. U.S., was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and that body, in a landmark decision, ruled that Black Americans had no constitutionally protected right to employment.

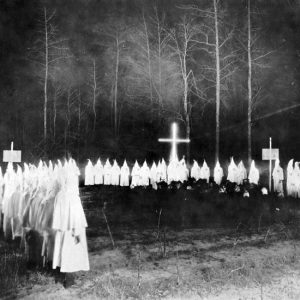

Meanwhile, the lynching of African Americans, which had reached a peak in the 1890s, began to taper off in the early twentieth century, but highly publicized lynchings still occurred—one in 1921 in Mississippi County (Henry Lowery) and one in Little Rock in 1927 (John Carter). The Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which had revived during and immediately after World War I, did not play a major role in either of those lynchings but became a potent force in state politics, particularly in the 1920s. The Klan had broadened its list of targets in this twentieth-century reincarnation, however, and included Jews, Catholics, foreigners, and bootleggers. Only bootleggers were in sufficient supply in Arkansas to attract their attention, so blacks generally became a prime target.

The most notorious case of mob violence against Black citizens was the Elaine Massacre, which occurred in 1919 in Phillips County. Black farmers near Elaine (Phillips County) formed the Progressive Household Union of America that year and hired Ulysses Bratton, a white Little Rock attorney, to file suits against the planters for whom they worked. Believing they were being cheated by the planters, they sought to secure a fair settlement, and Bratton, a former federal prosecutor who had pursued peonage investigations earlier in the century, agreed to represent them. Even as Bratton was investigating their claims and gathering evidence, a shooting occurred outside a church where Black union members were meeting on the night of September 30, 1919, leaving one white man wounded and another dead. The next three days witnessed mass violence against Black men, women, and children, as mobs of whites from surrounding counties and from Mississippi sought to put down what they believed to be a Black rebellion. Gov. Charles Brough arranged for federal troops to intervene, and their first order of business was to disarm everyone, Black and white. Twelve Black men were subsequently condemned to death, largely on the basis of coerced testimony in trials that lasted only minutes. The NAACP launched an investigation and pursued a series of appeals that eventually resulted in their release, with six of them being released following the U.S. Supreme Court case of Moore v. Dempsey. Scipio Jones, a prominent black attorney in Little Rock, played a major role in representing the twelve men, and many other Black Arkansans contributed to the cost of the appeals.

Economic Opportunities and Challenges

Had Arkansas been in a better position when World War I broke out, it might have capitalized on the business of the production of war supplies. The war did result in a boom in prices for agricultural and other commodities already produced in Arkansas: the timber, coal, zinc, and bauxite industries all experienced new levels of production and profits. As historian Carl Moneyhon suggests, moreover, the war further integrated Arkansas into the national culture by bringing out-of-state troops to Camp Pike in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Eberts Field in Lonoke County. More than 71,000 Arkansas soldiers left the state to serve in the war, and many returned to bring a new world of experiences to Arkansas. Meanwhile, those on the home front participated in Red Cross drives and Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) fundraisers and otherwise focused attention on matters far from home. Even notorious repression of dissent against the war became a part of the Arkansas experience when an attempt to arrest draft evaders in Cleburne County led to an armed confrontation in 1918 in what is known as the Cleburne County Draft War. Additionally, the flu epidemic of 1918 killed more than 7,000 Arkansans, several times more than the state lost during World War I.

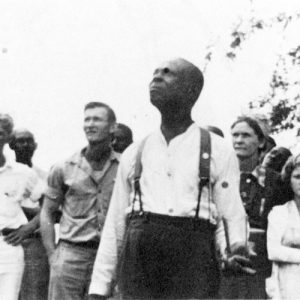

Although the war brought economic opportunity to certain industries in Arkansas, the postwar period brought challenges, both social and economic. Some historians view the Elaine Massacre as one manifestation of postwar readjustment, as labor and race riots escalated across the nation in 1919 and 1920. By 1920, the bottom fell out of the agricultural market, with cotton going from thirty-seven cents to six cents per pound. Although these prices recovered during the 1920s, it was too little, too late for many farmers, and then natural disasters followed in 1927 and again in 1930. The Flood of 1927 inundated 2,024,210 acres in Arkansas along the Mississippi River and its tributaries, and had it not been for a well-organized Red Cross relief effort, many of the state’s citizens would have been left in dire circumstances. Water remained on many thousands of acres well into the summer, preventing crops from being planted. The flood was followed in 1930 with a severe drought that also necessitated Red Cross relief and exposed the poverty of rural Arkansas to the nation. Families were discovered on the verge of starvation, and it became clear that the drought itself was only partially to blame. The endemic poverty of the rural population was merely exacerbated by the drought. Frustration levels were high, and when farmers in England (Lonoke County) in January 1931 demanded Red Cross relief that was not immediately forthcoming, local merchants were prevailed upon to distribute supplies to them.

The Great Depression

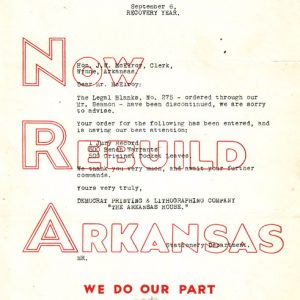

The Great Depression came to Arkansas long before the stock market crash of 1929. Indeed the 1920s had been a nightmare for many of the state’s citizens. By the end of the decade, many taxpayers were unable to pay their school, road, and drainage taxes, and the drought of 1930 merely delivered a final crippling blow. By 1932, the price of cotton had dropped to six cents a pound, far below the cost of production. In fact, no crop paid for itself, and merchants and businessmen who depended upon the health of the agricultural economy—which would have been most of them—were equally hard hit. Banks were closing their doors, leaving depositors stranded and without funds. By the time that Gov. Futrell took office in 1933, nearly forty percent of the state’s labor force was unemployed. Believing that the legislature had been guilty of profligate spending, he proposed two amendments to the state constitution that severely restricted the taxing and spending power of the legislature—and of the state in general—and marked a dramatic departure from the direction that progressive governors had been taking the state in the previous three decades. Futrell, a fiscal conservative who believed fervently that the state should play a very small role in the affairs of its citizens, proposed the Nineteenth Amendment, which limited legislative appropriations to a fixed amount and required a three-fourths vote in each house of the legislature or approval of the voters in a general election before taxes could be increased. The Twentieth Amendment required voter approval before the state could issue new bonds. Voters approved both amendments in a subsequent election.

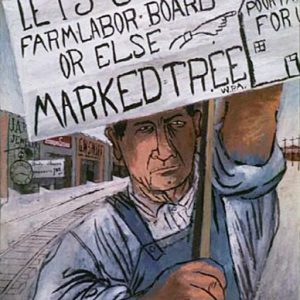

Meanwhile, trouble of another sort was brewing in the Arkansas Delta. In 1934, Black and white tenants and sharecroppers united under the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU) and began to object to the way Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) programs were being implemented. The STFU brought up two major issues. First, they objected to the way that planters were appropriating crop reduction payments—funds they received in return for “renting” acres to the federal government in return for not planting certain crops, such as cotton. Second, because they were no longer growing such labor intensive crops, many planters evicted extraneous tenants. Although he sided with the planters, publicity surrounding violent attacks on union members, as well as the agitation of the union’s leadership in Washington DC, forced Futrell to establish a state commission to study the situation. Although the STFU never achieved its goals, it attracted wide attention to the plight of the state’s rural poor, and one of its founders, H. L. Mitchell, claimed that the integrated union laid the foundation for the civil rights movement that emerged in the 1950s.

By the time Futrell left office in 1937, the state was operating on a cash basis and actually enjoyed a treasury surplus. His retrenchment efforts and the new taxes imposed on liquor and gambling were largely responsible, but many in Arkansas would have suffered had it not been for the massive amount of federal money pouring into the state through the FERA, the AAA, and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The WPA hired tens of thousands of Arkansans in construction projects, including building roads and erecting public buildings. Other WPA employees interviewed former slaves, wrote county histories, and collected questionnaires on churches throughout the state. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), meanwhile, put many young Arkansas men to work in camps in Arkansas, creating a number of state parks.

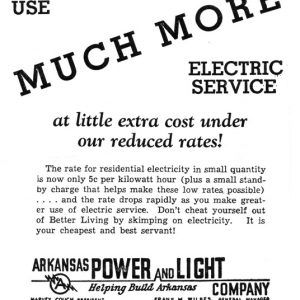

Not all New Deal programs were as successful. The Rural Electrification Administration (REA) ran into stiff opposition from Harvey Couch’s Arkansas Power & Light Company (AP&L), which wanted to preserve the rural electric market for itself. Although electrical service expanded in Arkansas between 1900 and 1940, exposing tens of thousands of the state’s people to modern conveniences, electricity reached many rural areas only after World War II.

Image and Reality

Arkansas’s economic woes, together with its treacherous racial history, contributed to an ongoing problem with its image. The famous pundit H. L. Mencken referred to Arkansas as the “Sahara of the Bozart,” referring not merely to its racial legacy but to the struggle against the teaching of evolution in the state. As religious fundamentalism, which emerged in the late nineteenth century, gained strength in the 1920s, anti-evolution became one of its most important causes. In 1924, the Arkansas Baptist State Convention rejected the theory of evolution and began pressing the legislature to enact an anti-evolution law. Unable to secure passage of the Rotenberry Bill in 1926, the supporters of the measure secured enough votes to put an anti-evolution bill on the ballot in 1928, and it swept to victory.

Many Arkansans were uncomfortable with the image fashioned by Mencken, just as they became resentful of certain 1930s radio personalities who played on the hillbilly characterization of the Arkansas Ozarks. Lum and Abner (Chester Lauck and Norris Goff) and comedian Bob Burns both turned successful radio programs into movie careers and took their characterizations to a national audience. As historian Ben Johnson and journalist and historian Bob Lancaster suggest, Burns’s form of humor was particularly galling to many Arkansans because he made the Arkansas hillbilly the butt of his jokes, while Lum and Abner merely used “the rusticity of the characters” as flavoring. Regardless, much of America took from both shows a distorted image of Arkansas, which they came to see as a state peopled with ignorant mountain folk. There was much more to the state, to be sure, and even as these radio programs were misinforming the nation, poet John Gould Fletcher, who was one of the lost generation of writers who endured a self-imposed exile in Paris in the 1920s, was gaining acclaim. He composed a lengthy ode to celebrate the state’s centennial in 1936 and went on to win the Pulitzer Prize in poetry in 1939.

At the same time, Fletcher also contributed to the emergence of a new appreciation of Arkansas’s folk culture. In 1935, he visited Emma Dusenbury near Mena (Polk County), who sung a number of forgotten songs. His account of his visit with her inspired others to record them and place the recordings in the Library of Congress. One of those who visited her was folklorist Vance Randolph, who interviewed mountain folk in the Ozarks and recorded much of their music. Musicologist John Lomax, meanwhile, visited Arkansas prisons and recorded “Rock Island Line,” which was later made famous by Leadbelly, thereby exposing the rich blues music of the state. Some communities eventually realized the commercial value of celebrating their folk culture and began to capitalize on it by sponsoring festivals that featured folk art and music. The King Biscuit Blues Hour, broadcast from Helena (Phillips County), exemplified this and, as well, the arrival of radio entertainment in Arkansas. From Helena in the Delta to Mountain View (Stone County) in the Ozarks, communities began to use the rustic image rather than run from it. Others of a more typically scholarly frame of mind began to lay the foundation for preserving and promoting the state’s history. The Arkansas Historical Association (AHA) published a few volumes on Arkansas history in the first decade of the twentieth century, but that organization was then eclipsed by the Arkansas History Commission (now called the Arkansas State Archives), created in 1905. Although the AHC was under-funded and little appreciated, it struggled to create an archive to preserve documentary evidence that later historians would find useful. In 1930, two history professors (David Y. Thomas and J. H. Atkinson) began to agitate for the re-creation of the AHA, hoping to promote, once again, the publication of scholarship on the state’s history. It was 1941 before they were successful, but the state has not been without its historical scholars since that time.

Conclusion

Between 1900 and 1940, the state went through a series of changes and grappled with the challenges confronting it. Some progressive reforms, such as Prohibition, fell away as economic demands took precedence. Others, such as women’s suffrage and the ending of convict leasing, endured. By the end of the period, the state had turned away from activist state government and embraced federal programs that oriented it ever more toward dependence upon the national treasury, a trend that continued in the decades that followed. As World War II loomed, however, the state was ill prepared, just as it had been in 1917, to make the most of the opportunities presented by the need to increase industrial production for the war effort. Its manufacturing sector remained a far distant second to the agricultural economy.

For additional information:

Arsenault, Raymond. Wild Ass of the Ozarks: Jeff Davis and the Social Bases of Southern Politics. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1984.

Barnes, Kenneth C. The Ku Klux Klan in 1920s Arkansas: How Protestant White Nationalism Came to Rule a State. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2021.

Blair, Diane D., and Jay Barth. Arkansas Politics and Government: Do the People Rule? 2d. ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Blevins, Brooks. Hill Folks: A History of Ozarkers & Their Image. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Bolsterli, Margaret Jones. Born in the Delta: Reflections on the Making of a Southern White Sensibility. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1991.

Dougan, Michael. Arkansas Odyssey: The Saga of Arkansas from Prehistoric Times to Present. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1994.

Foster, Buckley T. So Great Was the Slaughter: Market Hunters, Sportsmen, and Wildlife Conservation in Arkansas. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2025.

Gordon, Fon Louise. Caste and Class: The Black Experience in Arkansas, 1880–1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995.

Graves, John William. Town and Country: Race Relations in an Urban-Rural Context, Arkansas, 1865–1905. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Grubbs, Donald H. Cry from the Cotton: The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and the New Deal. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Holley, Donald. The Second Great Emancipation: The Mechanical Cotton Picker, Black Migration, and How They Shaped the Modern South. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Johnson, Ben. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

———. Fierce Solitude: The Life of John Gould Fletcher. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994

Ledbetter, Calvin R., Jr. Carpenter from Conway: George Washington Donaghey as Governor of Arkansas, 1909–1913. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Lisenby, Foy. Charles Hillman Brough: A Biography. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

McNeilly, Donald P. The Old South Frontier: Cotton Plantations and the Formation of Arkansas Society, 1819–1861. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Moneyhon, Carl. Arkansas and the New South, 1874–1929. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Mitchell, H. L. Mean Things Happening in This Land: The Life and Times of H. L. Mitchell, Cofounder of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union. Montclair, NJ: Allanheld, Osmun, 1979.

Niswonger, Richard L. Arkansas Democratic Politics, 1896–1920. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Polston, Michael D., and Guy Lancaster, eds. To Can the Kaiser: Arkansas and the Great War. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2015.

Smith, Kenneth L. Sawmill: The Story of Cutting the Last Great Virgin Forest East of the Rockies. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

Stuck, Dorothy, and Nan Snow. Roberta: A Most Remarkable Fulbright. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Watkins, Patsy G. It’s All Done Gone: Arkansas Photographs from the Farm Security Administration Collection, 1935–1943. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018.

Whayne, Jeannie, Thomas DeBlack, George Sabo, and Morris S. Arnold. Arkansas: A Narrative History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Whayne, Jeannie, and Willard B. Gatewood, eds. Arkansas Delta: Land of Paradox. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Whayne, Jeannie M. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor, and Federal Favor in Twentieth-Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996.

Willis, James F. “Antitrust in Arkansas Politics during the Progressive Era.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Winter 2021): 436–467.

Jeannie Whayne

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Broncho Billy Anderson

Broncho Billy Anderson  Arkansas Children's Hospital Physical Therapy Equipment

Arkansas Children's Hospital Physical Therapy Equipment  Arkansas City Cotton Picker

Arkansas City Cotton Picker  Arkansas National Guard

Arkansas National Guard  Arkansas Power & Light (AP&L) Ad

Arkansas Power & Light (AP&L) Ad  "Big Bill Blues," Performed by "Big Bill" Broonzy

"Big Bill Blues," Performed by "Big Bill" Broonzy  Biplane Over Leslie

Biplane Over Leslie  Bonnie and Clyde

Bonnie and Clyde  Bootlegged Liquor

Bootlegged Liquor  Charles Brough at Elaine

Charles Brough at Elaine  Bob Burns with Bazooka

Bob Burns with Bazooka  Camp Pike Dance

Camp Pike Dance  Hattie and Thaddeus Caraway

Hattie and Thaddeus Caraway  William Carr

William Carr  John Carter Lynching

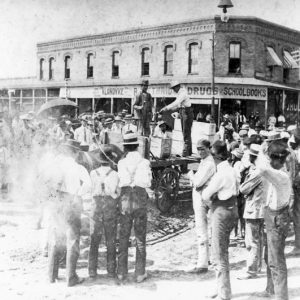

John Carter Lynching  Centennial Celebration

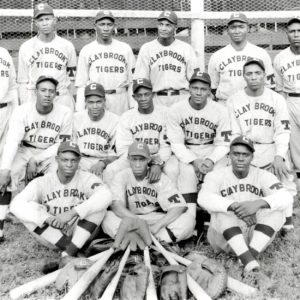

Centennial Celebration  Claybrook Tigers

Claybrook Tigers  Climber Automobile

Climber Automobile  Concatenated Order of Hoo-Hoo

Concatenated Order of Hoo-Hoo  Consolidated White River Academy Girls Basketball Team

Consolidated White River Academy Girls Basketball Team  "Dizzy" Dean

"Dizzy" Dean  Drainage Survey Crew

Drainage Survey Crew  Eberts Training Field Gunnery Plane

Eberts Training Field Gunnery Plane  Fargo Agricultural School

Fargo Agricultural School  Granata Winery

Granata Winery  Hope Watermelon Festival

Hope Watermelon Festival  Hotze and Fletcher

Hotze and Fletcher  Harry Hronas

Harry Hronas  Judsonia Hat Shop

Judsonia Hat Shop  King Crowley

King Crowley  Ku Klux Klan Rally

Ku Klux Klan Rally  Lake Village Flood

Lake Village Flood  Lest We Forget by Ben Shahn

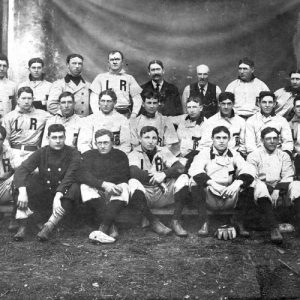

Lest We Forget by Ben Shahn  Little Rock Travelers

Little Rock Travelers  Now Rebuild Arkansas

Now Rebuild Arkansas  Oil Field Workers

Oil Field Workers  B. S. Petefish

B. S. Petefish  Public School Bible Verses List

Public School Bible Verses List  Rice Harvesting

Rice Harvesting  Babe Ruth at Oaklawn Park

Babe Ruth at Oaklawn Park  Sisters' School

Sisters' School  Southern Tenant Farmers' Union

Southern Tenant Farmers' Union  Star City Baptism

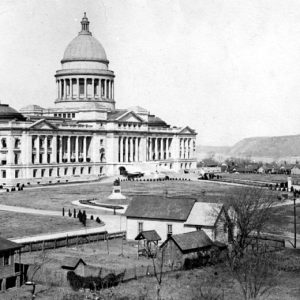

Star City Baptism  State Capitol Building

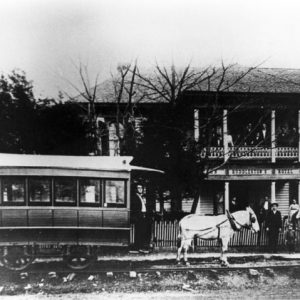

State Capitol Building  Sulphur Rock Street Car

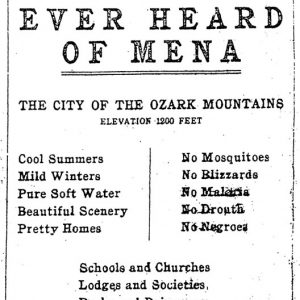

Sulphur Rock Street Car  Sundown Town Flyer

Sundown Town Flyer  Louise Thaden

Louise Thaden  UCV Reunion Parade

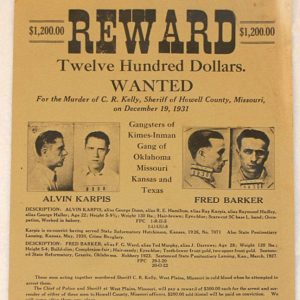

UCV Reunion Parade  Wanted Poster

Wanted Poster  WCTU Parade

WCTU Parade  Woodruff School

Woodruff School  World War I Soldiers

World War I Soldiers  Zinc General Store

Zinc General Store

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.