calsfoundation@cals.org

Moore v. Dempsey

The 1923 U.S. Supreme Court decision Moore v. Dempsey changed the nature of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The ruling allowed for federal courts to hear and examine evidence in state criminal cases to ensure that defendants had received due process.

The case that resulted in this decision was one of two lawsuits pursued by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the aftermath of the 1919 Elaine Massacre. After short trials, dominated by citizen mobs, twelve African Americans—six who became known as the Moore defendants and six who became known as the Ware defendants—were found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. Ultimately, the six Ware defendants were freed by the Arkansas Supreme Court; it took almost five and a half years and numerous legal efforts to have the six Moore defendants released from prison.

The Elaine Massacre was a riot that began on September 30, 1919, after shots were fired between white men and Black men outside of a Progressive Farmers and Household Union meeting in Hoop Spur, three miles north of Elaine. It is not clear exactly what happened at Hoop Spur, but it resulted in white mobs entering Elaine to put down a supposed Black insurrection. By the time order was restored on October 4, countless African Americans (100–200, according to historian Grif Stockley) and five white men had been killed; in addition, 285 African Americans were arrested during the riots.

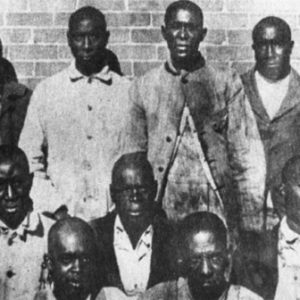

On October 31, 122 Black men were indicted by the Phillips County Grand Jury for their part in the riots. Judge J. M. Jackson began the trials on November 3. On this day, the six Moore defendants—Frank Moore, Frank and Ed Hicks, Joe Knox, Paul Hall, and Ed Coleman—were all tried for the murder of Clinton Lee. Frank Hicks was tried first, as he had been accused of shooting Lee, although one white witness, Tom Faulkner, could not identify Hicks as the shooter. According to newspaper reports, the jury took just eight minutes to deliberate over Hicks’s trial before finding him guilty of murder. Following Hicks’s trial, the remaining five men were tried together as accessories to murder and found guilty. All six were sentenced to death.

The NAACP, following a visit to Elaine by its secretary, Walter White, hired attorneys George C. Murphy and Scipio Africanus Jones to appeal the verdicts of the Moore defendants. Judge Jackson had appointed counsel to represent the indicted men, who were not given the chance to meet with their counsel; neither did their counsel allow them to take the stand in their own defense. The location of the trials, the length of time between the trials, and the speed of the trials were also cited as violating the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which grants everyone the right to a fair trial. However, the Arkansas Supreme Court, on March 29, 1920, upheld the original verdict and denied that there had been any wrongdoing. Murphy and Jones proceeded to appeal the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, which denied a hearing on October 11, 1920 (the same day that Murphy died of a heart attack), and Arkansas governor Thomas McRae set the date of execution for the Moore defendants as June 10, 1921.

Jones, alongside Murphy’s junior partner Edgar McHaney, had one last option, which they pursued two days before the date of execution. On June 8, 1921, they filed petitions for writs of habeas corpus in the Pulaski County Chancery Court, a court that did not have the jurisdiction to issue such writs. It had been their only option, however, because U.S. federal district judge Jacob Trieber was not available. Chancellor John E. Martineau issued an injunction against the defendants’ executions until a hearing could be held. Attorney General J. S. Utley immediately filed a petition for a writ of prohibition to dismiss the injunction by Martineau, citing that Martineau did not have jurisdiction in the matter. Despite Martineau’s clear lack of jurisdiction, Jones successfully persuaded the Arkansas Supreme Court to hold a hearing regarding the writ of prohibition before issuing a judgment. On June 20, the writ of prohibition was upheld by the Arkansas Supreme Court, and an appeal to the U.S Supreme Court was denied on August 4, 1921.

Having acquired new evidence during the summer of 1921—two affidavits from white witnesses present during the riots, which claimed that African Americans incarcerated after the riots had been subject to torture in order to testify against other African Americans—Jones once again filed writs of habeas corpus, this time in federal court. The hearing was held before District Judge J. H. Cotteral on September 26, and the attorney general simply responded to the hearing with a demurrer, which stated that even if the facts alleged by the NAACP were true, the appeals process had been completed by the state and it could not now be taken up in the federal courts. This was a stroke of luck for the NAACP because it meant that Judge Cotteral had to treat the alleged facts as true. Although Cotteral followed precedent and denied the writs of habeas corpus and sustained the demurrer, citing that the Arkansas Supreme Court had upheld the original trials as law-abiding and fair, he did allow the NAACP to appeal once again to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The NAACP now had a solid base from which to argue the case before the U.S. Supreme Court. By upholding the demurrer, Cotteral allowed the NAACP to present the case before the highest court without having to prove that the Moore defendants’ allegations were true. Instead, they had to present the case so as to demonstrate that the trial had denied the plaintiffs due process and that the appeals process afforded by the state had not corrected the failures of the initial trial.

Moorfield Storey, president of the NAACP, presented the oral arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court on January 9, 1923. Alongside the arguments raised by Murphy and Jones in previous appeals, Storey also emphasized that the Phillips County trials had been dominated by a citizen mob, something Murphy and Jones had not specifically argued before. On February 19, 1923, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its 6–2 decision in favor of the Moore defendants. The justices held that, considering the original trials had been mob dominated, the “corrective process afforded to the petitioners…does not seem sufficient,” and in such circumstances, federal judges had jurisdiction to overturn state criminal verdicts to rectify judicial failures of the state and to ensure that the defendants were granted due process.

Despite a favorable ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court, the case was not over; indeed, the court had called for a re-hearing in the district court. The Moore defendants were still in jail and could have faced a re-trial. However, Jones moved to evade any more trials and have the men released from jail. On November 3, 1923, Governor McRae, following a petition in Phillips County, announced that he had commuted the death sentences to twelve years in prison, making the men eligible for parole, as they had served a third of that time. It was not until January 13, 1925, that the six Moore defendants were finally freed from jail, having been granted indefinite furloughs from McRae.

Moore v. Dempsey was the first in a string of Supreme Court rulings that expanded the meaning of the due process clause over the twentieth century. Whereas the only means of appeal had once been in state courts, Moore v. Dempsey declared that state rulings could be challenged in federal court to examine cases to see if defendants had been denied their federal constitutional rights. It was a landmark ruling that sought to ensure that constitutional rights were protected.

For additional information:

Bailey, Kent Lee. “Prelude to Civil Rights: Moore v. Dempsey and the Aftermath of the 1919 Elaine, Arkansas Race Riot.” MA thesis, University of New Orleans, 1996.

Cortner, Richard C. A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.

Freedman, Eric M. Habeas Corpus: Rethinking the Great Writ of Liberty. New York: New York University Press, 2003.

Pruden, William H. III. “Cracking Open the Door: Moore v. Dempsey and the Fight for Justice.” In The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819–1919, edited by Guy Lancaster. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Stockley, Grif, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919. Rev. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Waterman, J. S., and E. E. Overton. “The Aftermath of Moore v. Dempsey.” St. Louis Law Review 18.2 (1932–1933): 117–126. Online at https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4642&context=law_lawreview (accessed June 27, 2025).

Whayne, Jeannie M. “Low Villains and Wickedness in High Places: Race and Class in the Elaine Riots.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Autumn 1999): 285–313.

Whitaker, Robert. On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice that Remade a Nation. New York: Crown, 2008.

Sarah Riva

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.