calsfoundation@cals.org

Frank Moore (1888–1932)

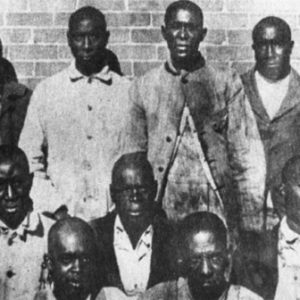

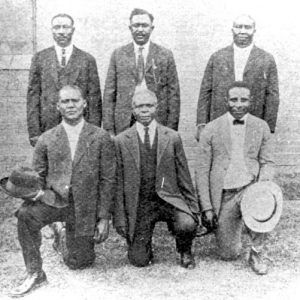

Frank Moore was one of twelve African-American men accused of murder and sentenced to death following the Elaine Massacre of 1919; his name was attached to the U.S. Supreme Court case of Moore v. Dempsey. After brief trials, the so-called Elaine Twelve—six who became known as the Moore defendants and six who became known as the Ware defendants—were found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. Ultimately, the Ware defendants were freed by the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1923; after numerous legal efforts, the Moore defendants were released in 1925.

Born in Gold Dust, Louisiana, in Avoyelles Parish, on May 1, 1888, Frank Moore was the son of sharecroppers James Moore and Mary Philips Moore. In 1917, Moore reported on his World War I draft registration form that he was working as a farmer in Tillar (Drew County). Moore was married by the time he registered for the draft, but the name of his spouse is unknown. Drafted later that year, he served as a private in the 162nd Depot Brigade before being honorably discharged on December 22, 1918.

After his discharge, Moore moved to Phillips County, where he sharecropped on the farm of Billy Archdale. Archdale started the planting season with thirteen black families sharecropping his land, but as the crop got closer to harvest, the planter drove all but four sharecropping families off the land by exaggerating their debts at his plantation store and cutting off their borrowing privileges, effectively starving the families. With no other recourse available to them, the families abandoned their shacks and crops, forfeiting their share of the profits to the planter. Not satisfied with merely stealing their share of the crop, Archdale confiscated any property of value the families had before driving them off his land. In May 1919, Moore became ill and attempted to borrow $10 from Archdale to go to the hospital, but the planter refused, forcing Moore to go to a friend for assistance. While Moore was in the hospital, Moore’s wife laid their rows of cotton and tended their crop.

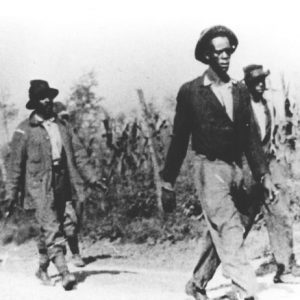

When Moore returned from the hospital, he was among the first of the sharecroppers in the area to join the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA). Taking a leadership role, he recruited farmers from neighboring farms as members of the union and helped to organize its meetings. Moore was present a union meeting at the Hoop Spur church outside of Elaine (Phillips County) when shooting broke out on September 30, 1919. After the violence erupted, he refused his wife’s urgings to desert their plot and abandon their claim to the cotton. Moore replied that he had “done nothing to leave for; that if he ran they would say that he was guilty of something, he wasn’t going to leave his crops.” Hiding his mother, wife, and younger siblings in the swamp, he returned to Elaine, where he was arrested along with his father and other union members.

After Moore’s arrest, Moore’s wife returned to Archdale’s farm in hopes of collecting the family’s possessions and the proceeds from the sale of the cotton they had harvested prior to the massacre. Anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells noted that Moore and his wife had harvested fifteen bales of cotton from the fourteen acres they had sharecropped on the farm and estimated that the value of their cotton was $3,150, half of which should have been paid to Moore. Upon returning to the farm, Moore’s wife discovered that their home had been looted and that all their possessions had been stolen. When she went to Archdale’s home to inquire about the proceeds from the sale of their cotton, she noticed that some of her clothes and furniture were inside and was told that her husband had been arrested and would be executed. When she asked about the monies owed to her husband for his share of the cotton, she was told by the planter that she could be killed and her body burned and buried where no one could find her if she did not leave his property. She left with only the clothes on her back.

On October 31, a total of 122 black men were indicted by the Phillips County Grand Jury for their part in the riots. Judge J. M. Jackson began the trials on November 3. On this day, the six Moore defendants—Moore, Frank and Ed Hicks, Joe Knox, Paul Hall, and Ed Coleman—were all tried for the murder of Clinton Lee. Frank Hicks was tried first, as he had been accused of shooting Lee, although one white witness, Tom Faulkner, could not identify Hicks as the shooter. According to newspaper reports, the jury took just eight minutes to deliberate over Hicks’s trial before finding him guilty of murder. The remaining five men, including Moore, were tried together as accessories to murder and found guilty. All six were sentenced to death, as were the six defendants in the separate Ware case.

The cases drew the attention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which galvanized support for the defendants and raised money for their legal counsel. It was in the defense of the Elaine Twelve that African-American attorney Scipio Jones rose to national acclaim. After a series of legal maneuvers and appeals, on February 19, 1923, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its 6–2 decision in favor of the Moore defendants. The justices held that, considering the original trials had been mob dominated, the “corrective process afforded to the petitioners…does not seem sufficient,” and in such circumstances, federal judges had jurisdiction to overturn state criminal verdicts to rectify judicial failures of the state and to ensure that the defendants were granted due process.

Despite a favorable ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court, the case was not over; indeed, the Court had called for a re-hearing in the district court. The Moore defendants were still in jail and could have faced a re-trial. However, Jones moved to evade any more trials and have the men released from jail. On November 3, 1923, Arkansas governor Thomas McRae, following a petition in Phillips County, announced that he had commuted the death sentences to twelve years in prison, making the men eligible for parole, as they had served a third of that time. It was not until January 14, 1925, however, that the six Moore defendants were finally freed from jail, having been granted indefinite furloughs from McRae the day before. The Ware defendants had been released in 1923.

After his release from jail, Moore moved to Chicago, Illinois. Working as a security guard for a real estate company and residing at 517 37th Street, Moore took in boarders to help pay his $30 per month rent. On April 15, 1932, Moore died, just shy of his forty-fourth birthday. His body was sent to Little Rock (Pulaski County), where he was buried in Little Rock National Cemetery on April 19, 1932. On March 6, 2020, a marker was dedicated in his honor at the cemetery.

For additional information:

Cortner, Richard C. A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.

Pruden, William H., III. “Cracking Open the Door: Moore v. Dempsey and the Fight for Justice.” In The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819–1919, edited by Guy Lancaster. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Stockley, Grif, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919. Rev. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Wells, Ida B. “The Arkansas Race Riot.” https://archive.org/details/TheArkansasRaceRiot/page/n1 (accessed June 19, 2019).

Whayne, Jeannie M. “Low Villains and Wickedness in High Places: Race and Class in the Elaine Riots.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Autumn 1999): 285–313.

Whitaker, Robert. On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice that Remade a Nation. New York: Crown, 2008.

Brian K. Mitchell, Kathryn M. Bryles, Andrew A. McClain, Jessica Parker

University of Arkansas Little Rock

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Elaine Massacre Defendants

Elaine Massacre Defendants  Elaine Massacre Defendants

Elaine Massacre Defendants  Elaine Massacre Prisoners

Elaine Massacre Prisoners  Frank Moore Memorial

Frank Moore Memorial  Frank Moore Tombstone

Frank Moore Tombstone

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.