calsfoundation@cals.org

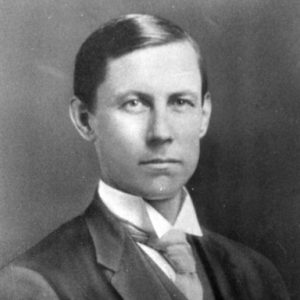

Ulysses Simpson Bratton (1868–1947)

Ulysses S. Bratton was a prominent Arkansas attorney in the first part of the twentieth century. His advocacy on behalf of the state’s African-American population made him enemies in the white community, and in the early 1920s he left Arkansas and resettled in Detroit, Michigan, where he established a successful law practice.

Ulysses Simpson Bratton was born on July 28, 1868, in Leslie (Searcy County) to Benjamin Bratton and Mary Redman Bratton. (He was probably named for General Ulysses S. Grant, as his father served with Union forces in the Third Arkansas Cavalry during the Civil War.) According to Fay Hempstead’s Historical Review of Arkansas, Bratton studied at Searcy County‘s public schools and at the Rally Hill Academy in Boone County. He was admitted to the bar in 1892 and practiced in Marshall (Searcy County). He later continued his study of the law, graduating from what is now the University of Arkansas School of Law in 1897. A member of the law firm of Bratton, Frazier and Bratton, he was admitted to practice in the United States Supreme Court by 1910.

On July 28, 1887, he married Martha T. Bryant. The couple eventually had six children, two of whom died in infancy.

Bratton quickly became involved in the community and the Republican Party. In 1893, he was elected county judge for Searcy County, and then in 1894 and 1896 he was elected to represent Searcy County in the Arkansas General Assembly. In 1897, he was appointed by President William McKinley to the position of assistant United States district attorney at Little Rock (Pulaski County), a job he held until 1907. In this position, he often sued Delta planters for violating federal laws against peonage, or debt slavery. In 1898 and 1899, he was active in the Marshall Mining Company with his father and other men in his family. The company was successful in zinc mining east of Marshall, taking the ore to Rush (Marion County) and Buffalo City (Baxter County).

In 1900, he was the unsuccessful Republican candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives from Arkansas’s Fifth District, and in the early part of the 1900s he was president of the Arkansas State League of Republican Clubs. Bratton was an influential supporter of William Howard Taft in Arkansas in 1908 and was a delegate to the 1908 convention that nominated Taft for president. Taft appointed him postmaster at Little Rock in 1910. The appointment was for a four-year term ending in February 1914, but Bratton, a sometimes controversial figure in the state’s political circles, resigned in late September 1913, tired of assorted political attacks, including charges that he had given preference to African Americans for post office jobs.

Returning to private practice with the firm Bratton, Frazier and Bratton, the man who had once successfully prosecuted white farmers under federal peonage laws became involved with the effort of the state’s African-American sharecroppers to unionize. Bratton had long spoken out against the exploitation of the sharecroppers and felt that unionization would help the situation. In fact, shortly before the Elaine Massacre, he and his son had been hired by the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America to sue landlords for the members’ share of the 1919 cotton crop. Bratton’s son Ocier was meeting with the sharecroppers when the violence broke out, and he was in one of the first groups that local authorities detained and questioned.

In the aftermath of the Elaine Massacre, Bratton played an important role in the effort to achieve justice for those falsely accused of murder. The interview he gave to National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) staffer Walter White helped shape the narrative about the events in Elaine that the NAACP and black newspapers were presenting. Bratton was able to share with White his previous work making it clear that the black sharecroppers were victims of a peonage system. Bratton also was actively involved with the NAACP’s legal effort, and when the case arrived at the U.S. Supreme Court, Bratton split duties with NAACP President Moorfield Storey in arguing the case before the Court.

However, while he could take great pride in the Court’s ruling in Moore v. Dempsey, neither the higher profile he gained from his work on the case nor his continuing support of the black sharecroppers endeared him to the white elite of Arkansas. In fact, he and his family became targets for abuse; they soon relocated to Detroit, as his major remaining client, a labor union, was located there.

Bratton and his family kept a low political profile after the move. After World War II, Bratton and his son Guy were partners in the founding of one of the large Detroit banks, City Bank, which was located in the Penobscot Building. According to one of Bratton’s grandchildren, he also helped build a local school. He continued to practice law, serving as the senior partner in the firm Bratton and Bratton. After a lengthy illness, Bratton died in Detroit on December 11, 1947.

For additional information:

Cortner, Richard. A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.

Johnston, James J. Shootin’s, Obituaries, Politics, Emigratin’, Socializin’, Commercializin’, and the Press: News Items from and about Searcy County, Arkansas, 1866–1901. Fayetteville, AR: Searcy County Publications, 1991.

Pruden, William H., III. “Cracking Open the Door: Moore v. Dempsey and the Fight for Justice.” In The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819–1919, edited by Guy Lancaster. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

“Senate Confirms Bratton.” Arkansas Gazette, February 8, 1910, p. 3.

Stockley, Grif, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919. Rev. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

William H. Pruden III

Ravenscroft School

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Law

Law Politics and Government

Politics and Government Ulysses S. Bratton

Ulysses S. Bratton

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.