calsfoundation@cals.org

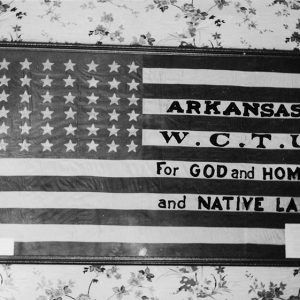

Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU)

aka: Arkansas Woman's Christian Temperance Union

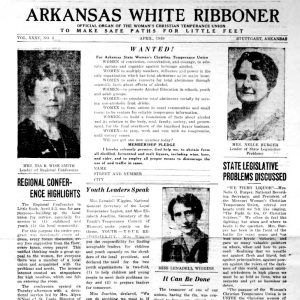

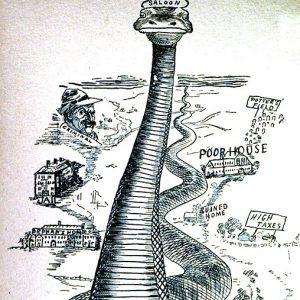

The Arkansas chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was established in 1879 in affiliation with the national WCTU, which originated as a state organization in Ohio in 1873. The Arkansas WCTU advocated for the abstinence of alcohol in Arkansas as well as supporting the state and national movements to prohibit the sale, manufacture, and consumption of alcohol. The organization also provided a political outlet for women in Arkansas through its campaigns, local option petitioning, and its newsletter, the Arkansas White Ribboner, which ran from 1888 to 1984.

In 1876, Lydia Chase, a national union member from Ohio, moved to Arkansas and gave a lecture on temperance to a group of women at a Presbyterian church in Monticello (Drew County). The lecture prompted several women to form the first local chapter there, and the Monticello union was recognized by the national organization in 1878. By 1900, there were eight local chapters. As local unions increased throughout Arkansas, a state chapter in Little Rock (Pulaski County) was established in 1879 to unite them.

The state and local chapters in Arkansas gained political strength through a court decision in Blackwell v. State of Arkansas. The Arkansas Supreme Court ruled that adult women (who did not have the right to vote at this time) could campaign and sign local option petitions to prohibit any sale of spirituous liquor within three miles of public schools, institutions, and churches. The law was amended by the Arkansas General Assembly in compliance with the ruling in 1881. In the same year, state and local chapters succeeded in local option petitions in Columbia, Fulton, Howard, Lonoke, Marion, and Sebastian counties.

In 1891, the Arkansas WCTU challenged the Tennessee Brewery Company over the use of the Little Rock Arsenal grounds. The company wanted to purchase the grounds and build a saloon and small garden. The union’s state committee members responded with a petition drive totaling 925 signatures along with personal letters to the Arkansas General Assembly. The petition proposed the grounds be given to the City of Little Rock for educational and recreational purposes. As the Arkansas General Assembly debated over the arsenal grounds, the Tennessee Brewery Company dropped its proposal. Senator James Jones then submitted a bill to donate the grounds to the City of Little Rock; they would later become MacArthur Park.

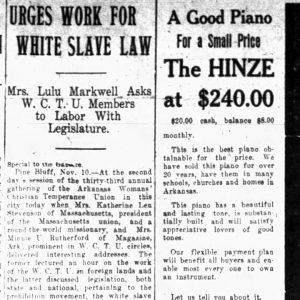

The state chapter attempted to expand its membership in the early 1900s by creating a division dedicated to bringing African-American communities into their activities. However, in 1908, a “dry vote” was held in Pulaski County. When it failed, leaders in the state chapter blamed African-Americans voter for the unsuccessful campaign. This included Arkansas WCTU president Lulu Markwell, who reported that African-American communities were interfering with the rights of white Christians. (Markwell would later leave the union to join the Women of the Ku Klux Klan, which formed in 1923.) In 1916, a motion was made by the state chapter for two African-American women to attend the annual state convention. Although, at its height, the WCTU would have local unions in almost every county, an African-American chapter was never formed, and the organization struggled to gain members from their communities.

Despite their failed efforts, the Arkansas WCTU soon gained the attention of the nationally recognized Carry Nation. Nation began her tour and protests through Arkansas in 1905 and had her first arrest in Hot Springs (Garland County) when she broke into a spa and bar to attack drinking and gambling activities; she was arrested again in Little Rock. Despite her arrests and the fact that she considered Jeff Davis, who served as Arkansas’s governor from 1901 to 1907, to be the worst governor in the United States, Carry Nation settled in Eureka Springs (Carroll County) and stayed in the state until her death in 1911.

The state chapter began working on collaborative efforts with the Arkansas Anti-Saloon League. Working independently, both organizations lobbied support in the passage of the Newberry Act—introduced by House Representative Farrar Newberry—which banned the manufacture and sale of alcohol throughout the entire state. The bill was signed into law by Governor George Hays in February 1915.

Following the Twenty-First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which repealed prohibition throughout the country in 1933, the state and local chapters continued local option petitions, dry-county elections, and state legislation support to prohibit or control the selling of alcohol. During World War II, the state chapter led a campaign of public letters, local and state newspaper articles, and sent a petition of 4,000 names to the U.S. Congress in support of the Sheppard bill. The bill—introduced to the U.S. Congress by Senator Morris Sheppard—prohibited the sale of alcohol to military camps in the United States. This included Camp Pike—later named Camp Joseph T. Robinson—in North Little Rock (Pulaski County). Although the bill did not pass in 1942, the state and local chapters continued their support by sending prohibition literature and films to Camp Pike.

In 1950, the Arkansas WCTU campaigned for Act No. 2. The act, if passed, would have limited the amount of alcohol a store or individual could possess in Arkansas to one quart. The act was petitioned by the Arkansas United Drys, which was a collaboration between the Arkansas WCTU and the Arkansas Temperance League. The petition sparked a counter campaign by O. J. Greene called Arkansas Against Prohibition. The Arkansas Against Prohibition group first berated the Arkansas United Drys for running afoul of Arkansas’s Act 157, which limited any political petition campaign budget to $25,000. The Arkansas United Drys and Arkansas Against Prohibition then took a case up to the Arkansas Supreme Court regarding forged signatures on the petition. Despite these challenges, Act No. 2 reached the public ballot. In total, members of the WCTU provided 30,000 leaflets, held five parades, and gave $1,000 in contributions. Act No. 2, however, did not pass, receiving only about forty-two percent of the vote.

The state and local chapters continued their support on county dry elections for the next few decades. Due to their lack of support and funding, the local and state chapters dissolved by 1985, though the remaining members continued to support the national and global WCTU.

For additional information:

Arkansas Woman’s Christian Temperance Union Records, MSS.97.30. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://arstudies.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/findingaids/id/7376/ (accessed December 17, 2021).

Fondren, Michael. “The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union on Local, State, and Federal Government: An Arkansas Case Study, 1879–1984.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2018.

Johnson, Ben. John Barleycorn Must Die: The War Against Drink in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

———. “‘The Staunchest of the Stout-Hearted Women’: The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the Varieties of Reform in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Autumn 2020): 193–217.

Knoll, Jessie Lowe. A Partial Fruition: A History of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union of Arkansas. Little Rock, AR: Woman’s Christian Temperance Union of Arkansas, Inc., 1951.

Nation, Carry. The Use and Need of the Life of Carry A. Nation. Topeka, KS: F.M. Steves & Sons, 1909.

Woman’s Christian Temperance Union Collection, UALR.MS.0086. Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Wilkerson, Jane Ann. “Little Rock’s Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, 1888 to 1903.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2009.

Michael Fondren

Fayetteville, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.