calsfoundation@cals.org

Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK)

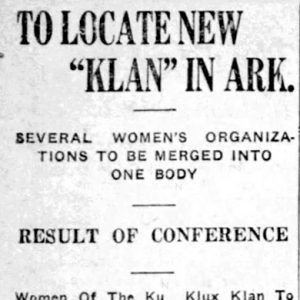

Headquartered in Little Rock (Pulaski County), the national Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK) was formed on June 10, 1923, as a result of the exclusively male Ku Klux Klan’s desire to create a like-minded women’s auxiliary that would bring together the existing informal, pro-Klan women’s groups, including the Grand League of Protestant Women, the White American Protestants (WAP), and the Ladies of the Invisible Empire (LOTIE). However, the group was ultimately short lived, waning in influence with its male counterpart.

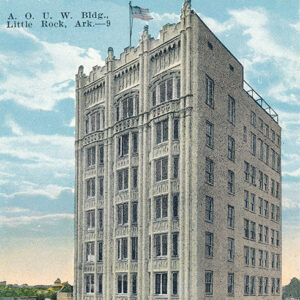

Lulu Markwell, a civically active Little Rock resident and former president of Arkansas’s chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) for twenty years, was the national organization’s first Imperial Commander, establishing its national office in Little Rock’s Ancient Order of United Workmen hall. According to historian Kathleen Blee, by November 1923, the WKKK had chapters in all forty-eight states and boasted a membership of 250,000. After Markwell’s resignation in June 1924, Robbie Gill, the WKKK’s Imperial Kligrapp, or secretary, replaced her as the group’s leader. A year later, Gill married the Arkansas Klan’s Grand Dragon, lawyer James A. Comer, who had been instrumental in convincing the Klan to ratify the WKKK’s charter. Comer continued his involvement with the WKKK, serving as their Imperial Klonsel, or attorney—involvement that soon caused problems for the organization.

From 1923 to 1931, the Little Rock–based national WKKK wrote, published, and disseminated numerous documents in which the Imperial Officers set forth the tenets to which all members were to adhere. To qualify for membership, one had to be a native-born, white, Protestant woman; membership in turn signaled a Klanswoman’s belief in Christianity “as practiced by enlightened Protestant churches,” the separation of church and state, the home as society’s foundation, free public schooling, the “supremacy of the Constitution of the United States,” freedom of speech and worship, impartial justice, no racial mixing, and immigration restriction. The WKKK viewed racial mixing as an offense parallel to treason, stating that “intermingling” was “opposed to the laws of God and man.” Promoting a nativist ideology of “America First,” the WKKK denounced immigrants and Catholics as “un-American,” claiming Protestantism as the birthright of Americans and that the United States was a country founded “not for the refuse population of other lands.” Klanswomen understood themselves as emancipated women whose role as voters—a right obtained only three years prior to the WKKK’s founding—was essential for the protection and purification of the country’s political, social, and moral fabrics.

The WKKK consisted of local chapters, provinces (county units), realms (regional/state units), and the Invisible Empire (national unit), with each group governed by officers exercising various executive, legislative, and judicial powers. Ritualized meetings, initiation ceremonies, and secret funeral services—interspersed with both Christian hymns and patriotic songs—blended the secular and the sacred. While the WKKK’s internal documents reveal a great deal about their tenets and ideology, records concerning the exact nature of Klanswomen’s activities in Arkansas and across the nation are sparse. However, the WKKK did briefly operate Klan Haven Orphanage in Little Rock, to case for the orphaned children of Klansmen and Klanswomen.

It is clear that only two years into its existence, the WKKK began to encounter some difficulties. In August 1925, Alice B. Cloud of Dallas, Texas—who had been Vice Commander at the time of Markwell’s resignation—filed a lawsuit with two other Klanswomen against WKKK head Robbie Gill Comer and her husband, claiming that the Comers had put WKKK funds toward their personal use and that Cloud had been the rightful successor to Markwell’s position. Two more lawsuits followed, and a judge eventually allowed Cloud and her fellow plaintiffs to look at the WKKK’s financial records. Those records revealed the Comers as greatly profiting from sales of WKKK garb and as having “squandered $70,000 of WKKK funds, equipping WKKK headquarters with goldfish, songbirds, police dogs, flowers, and a piano and purchasing for their own use a $5,000 sedan.”

A few weeks later, members of the Little Rock KKK broke away to form a separate organization due to their dislike of Judge Comer’s ineffective leadership; Little Rock’s Klanswomen also broke away from the national WKKK, according to historian Charles Alexander. In general, the WKKK’s membership waned with that of the male Klan; according to historian Kathleen Blee, by 1930, membership had dropped to fewer than 50,000 men and women due to internal problems of competing leadership and financial corruption, as well as the increased visibility of the male Klan’s violence. Publication of the WKKK’s documents appears to have continued into the early 1930s, but the extent to which the organization’s chapters remained active is unknown.

For additional information:

Alexander, Charles C. The Ku Klux Klan in the Southwest. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995.

Barnes, Kenneth C. The Ku Klux Klan in 1920s Arkansas: How Protestant White Nationalism Came to Rule a State. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2021.

Blee, Kathleen. Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

Kerbawy, Kelli R. “Knights in White Satin: Women of the Ku Klux Klan.” MA thesis, Marshall University, 2007.

McGehee, Margaret T. “Beneath the Sheets: An Intellectual History of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK), 1923–31.” MA thesis, University of Mississippi, 2000.

Seaver, Darcy L. “Women in the Hood: Women in 1920s Ku Klux Klan Publications.” MA thesis, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 1992.

Margaret T. McGehee

Emory University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.