calsfoundation@cals.org

Lulu Alice Boyers Markwell (1865–1941)

Lulu Markwell was the first Imperial Commander for the national Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK) organization and president of the Arkansas chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).

Lulu Alice Boyers was born in Corydon, Indiana, on October 1, 1865. She was the only daughter of Benjamin Boyers, who was a carpenter, and his wife, Phoebe Mathes Boyers, who was a housekeeper.

Boyers attended Corydon public schools before enrolling in Bryant & Stratton Business College in Louisville, Kentucky (now Sullivan University). The nationwide chain of colleges was prominent during the era, with alumni such as Henry Ford and John D. Rockefeller. After she graduated, Boyers’s professional career began in Little Rock (Pulaski County), including four years in teaching and one year in courtroom stenography.

On June 15, 1893, she married John W. Markwell, a dentist, in Little Rock. The two had grown up near one another in Harrison County, Indiana. In the years following their wedding, Boyers’s mother died, and her widowed father moved into the couple’s home. They also had two African-American domestic servants, according to the 1920 federal census. The couple had no known surviving children.

Markwell was civically active in a variety of organizations and causes, including women’s suffrage, the Presbyterian Church, fraternal societies, and the state Democratic Party. In May 1912, Governor George Washington Donaghey appointed her as a delegate to the Southern Sociological Congress in Nashville, Tennessee. The object of the committee was to bring together Southerners interested in social welfare and the improvement of economic conditions in the South. Markwell later served as president of the Little Rock Board of Censors, a municipal body designed to protect public morality in the city. The board was later reconstituted at the urging of the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA), which had grown concerned with the risqué content of the film industry. Markwell’s leadership, from 1921 to 1926, coincided with growth in the board’s activity prior to the tenure of her successor, Little Rock mayor Charles E. Moyer.

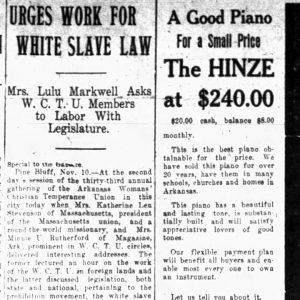

Markwell’s concern for civic morality led to her twenty-year involvement with the Arkansas Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. She served as state president during the 1910s and was a lecturer for the organization. She had previously presided over the Little Rock chapter, which bore her name. In the WCTU, Markwell worked to build a diverse coalition in support of statewide prohibition of alcohol. This service overlapped with membership in numerous women’s patriotic societies and Protestant organizations.

At the age of fifty-eight, Markwell was named the first Imperial Commander for the newly created Women of the Ku Klux Klan. The national organization formed on June 10, 1923, in Little Rock’s Ancient Order of United Workmen Hall as a women’s counterpart to the men-only Ku Klux Klan (KKK). The Klan hoped the women’s auxiliary could rally pro-Klan, nativist, and/or patriotic women’s groups around its cause. As the organization’s first leader, Markwell was influential in expanding membership and outreach. She believed that the WKKK had the potential to further the interests of women and advocate for social reform. She embarked on recruiting trips throughout the United States, particularly in the Northwest and West. To increase the organizational visibility among women, she also created female field positions and hired female kleagles (or KKK recruiting officers). Under Markwell’s leadership, the WKKK established chapters in forty-eight states, and by 1924, was establishing fifty new locals per week. Markwell resigned in June 1924, giving no public explanation for her abrupt resignation. Robbie Gill Comer, the WKKK’s Imperial Kligrapp (or secretary), succeeded Markwell as leader.

Markwell died on August 5, 1941. She is buried in Oakland-Fraternal Cemetery in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Alexander, Charles C. The Ku Klux Klan in the Southwest. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995.

Berlet, Chip, and Matthew Lyons. Right-Wing Populism in America: Too Close for Comfort. New York: The Guilford Press, 2000.

Blee, Kathleen. Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

Kerbawy, Kelli R. “Knights in White Satin: Women of the Ku Klux Klan.” MA thesis, Marshall University, 2007.

McGehee, Margaret T. “Beneath the Sheets: An Intellectual History of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK), 1923–31.” MA thesis, University of Mississippi, 2000.

Seaver, Darcy L. “Women in the Hood: Women in 1920s Ku Klux Klan Publications.” MA thesis, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 1992.

Ryan Driskell Tate

St. Paul, Minnesota

Lulu Markwell

Lulu Markwell  Lulu Markwell Article

Lulu Markwell Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.