calsfoundation@cals.org

Aviation

Aviation history in Arkansas includes one pioneer inventor, a few attempts at commercial airplane production, a regional commuter airline, a now-national air freight company, and varying degrees of impact on the state’s communities. By the 1970s, aviation had become essential both for business use and for personal travel.

Balloons and Dirigibles

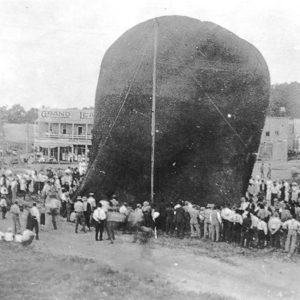

Balloon ascensions became popular throughout the United States in the 1850s, and balloons also figured in the Civil War, though none were deployed in Arkansas. There was an ascension in Yell County in 1879, and in 1902, balloonist Charles Geary came to Baxter County to perform, along with “Professor” Murgle, who demonstrated the parachute.

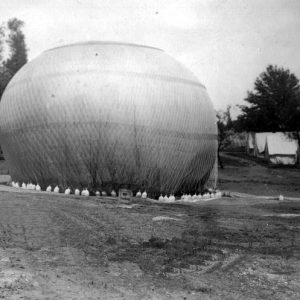

Balloon production was apparently limited to the Hot Springs Airship Company of Joel Troutt Rice and John A. Riggs, formed on February 24, 1908. “Joe” Rice had been working airships for more than ten years and had two flying-machine patents to his name by 1901. His first creation, The Arkansas Traveler, was fifty to seventy-five feet long. The steel carriage supported a motor and propeller. At the first test in Hot Springs (Garland County), the hydrogen-filled dirigible rose about ten feet off the ground before gently settling down. Riggs, the company’s treasurer, convinced Rice to move to New York, where Rice created an improved model, the American Eagle. It, however, never flew, and the legal battle that erupted between Rice and Riggs brought all work to a halt.

Early Airplanes

Heavier-than-air aviation began with Charles McDermott, whose patented inventions included a cotton-picking machine (#152,858) in 1874 and an iron wedge (#159,949) in 1875. However, it was #133,046, issued on November 12, 1872, that led to his fame and his nickname, “Flying Machine Charlie.”

McDermott’s invention was formally styled, “Improvement in Apparatus for Navigating the Air.” His machine consisted of some ten or more flaps. The operator, lying prone in the middle, operated the machine with his feet. McDermott exhibited models in Monticello (Drew County) and Little Rock (Pulaski County) before taking his inventions to the Arkansas exhibit at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876. Whether any of his machines actually flew is uncertain. However, there is a considerable similarity between the Wright brothers’ first machine and that of McDermott, the difference being that the Wrights’ had a gasoline motor.

Arkansas’s first well-documented flight took place in Fort Smith (Sebastian County) on May 21, 1910. James C. “Bud” Mars was the pilot of the Curtiss Bi-Plane that reached an estimated speed of sixty miles per hour. Central Arkansas’s first flight came on April 16, 1911, when pilot Joseph J. Pendergrass flew Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) banker William Henry Langford’s Curtiss biplane at Rob Roy (Jefferson County).

The year 1911 proved to be a bonanza for airplane enthusiasts, with air shows in Little Rock, Hot Springs, and Fort Smith. By that year, airplanes could fly at speeds from fifty to eighty miles an hour and reach altitudes of up to 3,000 feet. The first flight in Fayetteville (Washington County) was organized by Jay Fulbright, a local merchant, and featured Glenn Luther Martin, later the longtime head of Martin Aircraft. The same year saw the first air-mail service, and postcards were printed for the occasion. Fayetteville was also briefly home to Jerome S. Zerbe, who built the “Zerbe Air Sedan.” Featuring a fully enclosed cockpit and an ejector seat, it was tested by Fayetteville’s first test pilot, Tom Flannerty. Unfortunately, the machine would only hop.

World War I pushed aviation forward rapidly. Prior to America’s entry, enterprising young men made their way into English and French units. Arkansan John MacGavock Grider served with the British Eighty-fifth Squadron, dying in action in 1918. His diary, the basis for the book, War Birds, The Diary of an Unknown Aviator, became a bestseller in the 1920s, in part because it embodied elements of the “Lost Generation.”

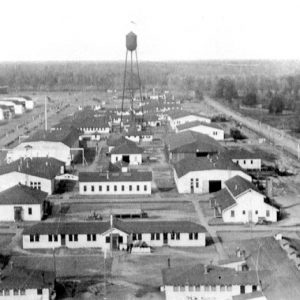

The entry of the United States into the war in 1917 led to creation of Eberts Field at Lonoke (Lonoke County). Would-be pilots trained on the Curtiss JN4, commonly called a “Jenny.” Among the prominent Arkansans who saw service were Field Kindley, who was born near Pea Ridge (Benton County), and Wendell Archibald Robertson, who ranked ninth in “kills” among American fighter pilots. Born in Oklahoma, Robertson grew up in Fort Smith.

The war’s end created a surplus of pilots. Many turned to barnstorming, a sort of miniature air show that often included wing-walking and other stunts. County fairs were good opportunities for flight, and local farmers reveled at the chance to take a ride over their farms and see them from the air. Pilots also turned to crop-dusting, an especially important part of the war against the destructive boll weevil, which involved dropping arsenic from sacks on the cotton fields below. One of these gypsy pilots was Charles Lindbergh, whose first night flight, commemorated by an obelisk at Lake Village (Chicot County), took place over Lake Chicot in April 1923.

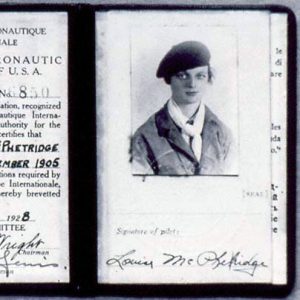

Early aviation offered opportunities for women. In 1912, Katherine Stinson, who was living at the time in Pine Bluff, became the fourth woman in America to get a pilot’s license. Forthwith, she appeared in England and then Japan. In the 1920s, Louise McPhetridge Thaden from Bentonville (Benton County) attained national recognition. Besides winning the Women’s Air Derby in 1929, she and co-pilot Blanche Noyes won the prestigious Bendix Trophy against male competition in 1936, flying from New York to Los Angeles in just under fifteen hours. The first known African American to receive Airman Certification Notification (a pilot’s license) was Pickens W. Black, a Jackson County planter from Blackville. His student pilot certification arrived on January 7, 1932, and his private pilot license on November 30, 1933. His last license was issued in 1958. Black liked to fly low over the cotton fields in the fall and terrify the cotton pickers.

As air traffic grew and commercial uses developed, it became necessary to create formal airfields. Amendment 13 to the Arkansas constitution authorized funding such projects. Little Rock built the first one in 1926 and received national attention when that year’s National Elimination Balloon and Aeroplane Races were held there on April 29–30. Pine Bluff followed, opening Toney Field in 1927. Fort Smith’s Alexander Field opened in 1927. Pilot Floyd H. Muncie, who worked for Ozark Airways and had more than 2,000 hours in the air, offered instruction. In 1928, Arkansas Air Tours began, supported by local enthusiasts who organized flying clubs.

Airmail service came to Little Rock on June 19, 1931, when American Airlines vice president Edward Vernon Rickenbacker took a sack of mail and loaded it on the fourteen-passenger tri-motor airplane. On September 8, 1935, the Arkansas Gazette complained that the two daily deliveries had stopped due to the field being too small. The newspaper hoped that the Works Progress Administration (WPA) might be able to address the problem, which it did by building the terminal.

Another component of Arkansas aviation was the creation in 1925 of the 154th Observation Squadron as part of the Arkansas National Guard. State Auditor John Carroll Cone, a World War I pilot, was a major proponent, and two years later, the squadron performed yeoman service during the Flood of 1927 in locating refugees, reporting levee breaks, and dropping medicines and supplies. They also carried the Batesville (Independence County) mail to Little Rock. Their aerial photographs documented conditions far better than land-based pictures. Afterward, the entire squadron received a peacetime citation from the secretary of war. National Guard pilot George Geyer Adams, who was killed when a propeller assembly exploded, was honored on November 11, 1941, when the Little Rock municipal airport was named Adams Field.

Advances in Aviation

Just as Arkansas briefly boasted of an automobile manufactory, the Climber, so too was the state home to airplane companies. The best known began as the Arkansas Aircraft Company before reorganizing as Command-Aire. Robert B. Snowden headed up the firm, and Little Rocket, its test plane, won the Cirrus International Air Derby in 1930. More than 300 aircraft were sold, but the Depression drove the company out of business. A more obscure aviation business operated out of Williford (Sharp County). Sometime early in the century, Luther Kellett ordered an airplane, assembled it, and took off from a local field. During the late 1920s, he opened a factory about which nothing is known.

Despite the hardships of the Great Depression, aviation in Arkansas continued to advance. The New Deal financed building airports through the Civil Works Program. In order to meet federal requirements, the airport in Jonesboro (Craighead County) was owned by City Water and Light, an improvement district, until 1977. Selling hay off the unused areas more than paid for expenses. Charles M. Taylor, a member of the “Blue Devils” exhibition team from the 154th Squadron, became the airport supervisor for the state of Arkansas in 1933. His work included cataloging all the forty-seven airports then in the state and getting each town to paint its name on rooftops with arrows marking the way to local airfields.

One important pilot of the 1930s was Frank Glasgow Tinker Jr. from DeWitt (Arkansas County). A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy in 1933 who then enlisted in the Army Air Corps, Tinker joined the Spanish Republican air force during Spain’s civil war, shooting down eight enemy planes and authoring a book, Some Still Live (Wings of War).

One other product of the 1930s was the founding of the Central Flying Service in Little Rock in 1939 by Claud Holbert and Ed Garbacz. The incentive for creating this commercial aircraft firm was the pre-war development of the federally funded Civil Pilot Training Program (CPTP) designed to turn civilians into pilots after a nine-week course. Fayetteville in 1936 had approved a $20,000 bond issue to create a city airport; CPTP began there in 1939. The first class of twenty included one woman, Maurice Ash, who became the first female to fly solo over the field. Raymond J. Ellis took over the program in 1940, founding Fayetteville Flying Services.

Pilot training figured prominently during World War II. During the war, seven bases opened: Walnut Ridge Army Flying School in Lawrence County, Grider Field at Pine Bluff, and others at Helena (Phillips County), Camden (Ouachita County), Stuttgart (Arkansas County), Blytheville (Mississippi County), and Newport (Jackson County). A total of 4,641 pilots trained at Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County) alone, and reaction to their extensive drinking habits resulted in Craighead County’s going dry during the war. Arkansas State College (now Arkansas State University) in Jonesboro sported a hangar and provided training to pilots; one graduate was Paul (Pete) Coughlin, who became nationally famous as the “Sergeant York of the Air” after he and his observer captured an estimated 150 prisoners during the Allied landing at Scoletti, Sicily. Fourteen Arkansans became “aces” (pilots with five or more “kills”), the most famous being Pierce McKennon. The Ninety-ninth Fighter Squadron (subsequently part of the Seventy-ninth Fighter Group) was the belated segregated air force established in 1939. Trained at Tuskegee, Alabama, and commonly called the Tuskegee Airmen, this elite group included three Arkansans: Herbert V. A. “Bud” Clark from Pine Bluff, Woodrow W. Crockett from Texarkana (Miller County), and Milton P. Crenchaw from Little Rock.

Wartime service could have political benefits. Nathan Gordon of Morrilton (Conway County), whose plane was named The Arkansas Traveler and sported a Razorback hog on the nose, won the Congressional Medal of Honor for his rescuing of downed crewpersons. In 1947, he was elected lieutenant governor, holding that office for twenty years.

Airports and Industry

The end of the war left some Arkansas communities with extensive airfields. The Walnut Ridge Army Flying School was chosen to serve as a airplane graveyard, and newly finished airplanes were flown in and converted into scrap. A different scenario unfolded at Fayetteville, where the municipal airport, named Drake Field in 1949, predated the war. Raymond J. Ellis’s Central Air Transport in 1946 flew 5,000 baby chickens for John Tyson from Joplin, Missouri, to Springdale (Washington County). Ellis started the state’s first commuter service (to Little Rock) in 1946. South Central Air Transport (SCAT) was but the first of his efforts; Scheduled Skyways, founded in 1953, was the most enduring. In 1954, Central Airlines came to Fayetteville, eventually merging with Frontier Airlines.

Technological developments resulted in bigger airplanes that needed longer runways. This often posed problems for airports without growing space. For instance, Drake Field’s runway was enlarged three times. However, efforts to create a regional field proved to be controversial. A 1965 study for the state urged creating a regional airport, but it took decades to agree on a site. One proposed solution, placing a new airport at Tontitown (Washington County), threatened to wipe out this Italian colony, along with its vineyards. Eventually, a remote site in Benton County became the home of what is now the Northwest Arkansas National Airport, opening on November 1, 1998. It was only the third commercial airport opened in Arkansas in the preceding twenty-five years.

Little Rock also experienced growing pains, in part because the airport site sat atop a major prehistoric village. There was also discontent with the name Adams Field, the use of which declined significantly. The physical limitations were reflected when an Arkansas-created company, Federal Express, founded in 1971, moved to Memphis in 1973 because of its superior airport facilities.

Aviation issues in government were handled by the Arkansas Aeronautical Commission. However, much political feuding surrounded this body until, in 1969, Edward W. “Eddie” Holland, one of Winthrop Rockefeller’s pilots, took over as head. Holland served until 1985 and, in the early years, was able to get increased state and federal aid for airport construction, with ten new airports being added, giving Arkansas a total of eighty-six by 1983. Approximately 100 existed in 2007.

With the start of the Cold War, Arkansas became home to two air force bases. Eaker Air Force Base was located outside of Blytheville in northeastern Arkansas; it closed in 1992. Little Rock Air Force Base (LFAFB) opened in 1955 and served as home to the Strategic Air Command. It has survived base closings, and the 188th Fighter Wing of the Air National Guard at Fort Smith successfully appealed its shutdown.

Missiles, too, were present in Arkansas in various forms. William L. Ripley, a North Little Rock (Pulaski County) science teacher, organized the Arkansas Amateur Rocket Society in the fall of 1957. On a much larger scale, in the 1960s, silos for Titan II missiles—intercontinental ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads—were established in Arkansas; the state became the site of the most publicized disaster in the history of the program when a Titan II missile exploded in its launch duct in 1980, killing one man and destroying the complex. Missiles were also manufactured in Arkansas at Lockheed Martin’s Camden plant. In 2006, Industryweek included the plant as one of the ten best in the United States.

Following the deregulation of passenger air service in the 1970s, the nation’s major carriers concentrated on their core markets (called hubs). Cutthroat competition ended the lives of virtually every American carrier company in less than twenty years. For would-be Arkansas travelers, an extended automobile trip to Memphis, Dallas, Tulsa, or Little Rock became necessary to secure a flight that often entailed many changes of planes in order to reach the desired destination. Things have not much improved in the twenty-first century.

Little Rock became home to Dassault-Falcon Jet Corporation, a major producer of business airplanes. The first factory opened in 1975 and, by 2007, employed more than 1,500 workers. The actual airplanes are made in France and then flown to Little Rock where, in the completion phase, the interiors are installed.

Historical Sites

Arkansas is home to many historic aviation-related sites. Still in existence is the first hangar for Adams Field. Built by Transcontinental Air at Waynoka, Oklahoma, in 1929, the hangar was purchased, dismantled, and then reconstructed at Adams Field in 1937. Other old hangars are at Drake Field in Fayetteville. Drake is also home to the Arkansas Air Museum and the Ozark Military Museum, and Eureka Springs has the Aviation Cadet Museum at Silver Wings Field. The Southwestern Proving Ground outside Hope (Hempstead County) was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999. Built prior to World War II, it was the third-longest runway in the United States when built. Other museums include the Fort Smith Air Museum and the Walnut Ridge Army Flying School Museum.

For additional information:

Arkansas Aviation Historical Society Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Aviation in Stone County.” Heritage of Stone 42.2 (2018): 1–59.

Boles, Keith J. “Jonesboro City Water and Light and the Jonesboro Airport.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 26 (Winter 1987–88): 9–18.

Diffee, Robert A. “Arkansas’s Early Aviation Heritage.” Pulaski County Historical Review 43 (Fall 1995): 50–64.

Eckels, Mike. FYV, The Story of Aviation in Fayetteville, Arkansas. N.p.: 2000.

Garner, Glenda. “Yesterday’s Williford.” Sharp County Journal 4 (April 1988): 4–55.

Hoyt, Robert D., Alphonse M. Hiegel, Stuart T. Hoyt, and Harrell E. Clendenin. A History of Aviation in Conway, Arkansas, 1917–2010: A Compilation of Events and Memories. Bowling Green, KY: Pip Printing, 2010.

Hudson, James J. In Clouds of Glory: American Airmen Who Flew with the British During the Great War. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Jordan, T. E. “Washington County’s First Flight.” Flashback 42 (August 1992): 1–5.

Kesterman, K. “I Remember: Early Days of Arkansas Flying.” Jefferson County Historical Quarterly 11.3 (1983): 20–23.

Mosenthin, H. Glenn. “’All Aboard’: Trans-Texas Airways Service at Stuttgart.” Grand Prairie Historical Bulletin 62 (April 2019): 32–39.

Rhodes, Larry D. “Arkansas Traveler: The Untold Story of the Hot Springs Airship.” The Record 41 (2000): 1–7.

Roesler, Alan L. “Flying under the Bridges in Little Rock: The Victory Loan Flying Circus, April 13, 1919.” Pulaski County Historical Review 63 (Spring 2015): 2–9.

Smith, William M., Jr. “The Right Plane at the Wrong Time: A Brief History of the Command-Aire Aircraft Company.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 51 (Autumn 1992): 224–246.

Thaden, Louise. High, Wide and Frightened. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2004.

Turner, Mary Nell. “Southwestern Proving Ground, 1941–1945.” Journal of the Hempstead County Historical Society (Spring 1986): 3–41.

Wallis, Dave. Eight Nine Romeo Poppa: The Story of Aviation in Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas Aviation Historical Society, 2000.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Arkansas Division of Aeronautics (ADA)

Arkansas Division of Aeronautics (ADA) Arkansas Wing, Civil Air Patrol

Arkansas Wing, Civil Air Patrol Boone County Regional Airport

Boone County Regional Airport Coffey, Cornelius Robinson

Coffey, Cornelius Robinson Dexter B. Florence Memorial Field

Dexter B. Florence Memorial Field Fort Smith Regional Airport

Fort Smith Regional Airport Green, Marlon DeWitt

Green, Marlon DeWitt Little Rock Aviation Supply Depot

Little Rock Aviation Supply Depot Lyle, Lewis Elton (Lew)

Lyle, Lewis Elton (Lew) Mena Intermountain Municipal Airport

Mena Intermountain Municipal Airport North Little Rock Municipal Airport

North Little Rock Municipal Airport Schilberg, Richard

Schilberg, Richard Silitch, Mary Frances

Silitch, Mary Frances Texarkana Regional Airport

Texarkana Regional Airport Transportation

Transportation Arkansas Aerospace Education Center

Arkansas Aerospace Education Center  Arkansas Air Museum

Arkansas Air Museum  Arkansas Air Museum

Arkansas Air Museum  Aviation Cadet Museum

Aviation Cadet Museum  B-58

B-58  Balloon Ascension

Balloon Ascension  Benton Airplane

Benton Airplane  Biplane Over Leslie

Biplane Over Leslie  Central Flying Service Hangar

Central Flying Service Hangar  Fred Darragh

Fred Darragh  Paul Douglas

Paul Douglas  Paul Douglas's WWII Plane

Paul Douglas's WWII Plane  Drake Field

Drake Field  Drake Field

Drake Field  Early Aviation

Early Aviation  Eberts Field Airplane

Eberts Field Airplane  Eberts Training Field Gunnery Plane

Eberts Training Field Gunnery Plane  Eberts Training Field

Eberts Training Field  Eberts Training Field

Eberts Training Field  Flippin Airport

Flippin Airport  KC-135 City of Little Rock

KC-135 City of Little Rock  Field Kindley

Field Kindley  Charles Lindbergh

Charles Lindbergh  Charles McDermott

Charles McDermott  James McDonnell

James McDonnell  Pierce McKennon

Pierce McKennon  Original Tuskegee Airmen

Original Tuskegee Airmen  Ozark Regional Airport

Ozark Regional Airport  RB-47 Razorback

RB-47 Razorback  Rice Seed Loading

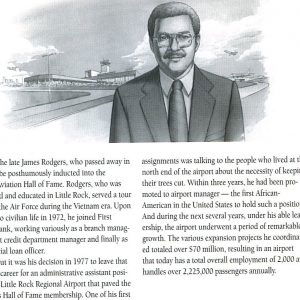

Rice Seed Loading  James Rodgers

James Rodgers  James Rodgers Induction

James Rodgers Induction  Richard Schilberg

Richard Schilberg  Mary Frances Silitch

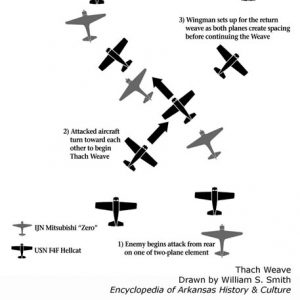

Mary Frances Silitch  Thach Weave

Thach Weave  Jimmie Thach

Jimmie Thach  Louise Thaden's Pilot License

Louise Thaden's Pilot License  Louise Thaden

Louise Thaden  UCV Reunion Balloon

UCV Reunion Balloon  Walnut Ridge Army Flying School

Walnut Ridge Army Flying School  Walnut Ridge Army Flying School B-32s

Walnut Ridge Army Flying School B-32s  Walnut Ridge Army Flying School BT-13

Walnut Ridge Army Flying School BT-13  Kenneth Wilson

Kenneth Wilson  Zerbe Air Sedan

Zerbe Air Sedan

J. D. “Johnny” Howe flew the first passenger flight for Delta Air Service, Inc. (Delta Air Lines) on June 17, 1929, from Dallas, TX, to Jackson, MS, with stops in Shreveport and Monroe, LA, along the way.

This quote is from the website of the Delta Heritage Museum in Atlanta, GA:

“J. D. ‘Johnny’ Howe, a tall, lanky Arkansas airman with six years flying experience. He previously worked as an agent for the Travel Air Company. Considered an excellent stunt flier, Howe had been one of the first pilots in the nation to receive a commercial pilot’s license.”