calsfoundation@cals.org

Mississippi County

| Region: | Northeast |

| County Seats: | Blytheville, Osceola |

| Established: | November 1, 1833 |

| Parent County: | Crittenden |

| Population: | 40,685 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 902.09 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

1,410 |

2,368 |

3,895 |

3,633 |

7,332 |

11,635 |

16,384 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

30,468 |

47,320 |

69,289 |

80,217 |

82,375 |

70,174 |

62,060 |

59,517 |

57,525 |

51,979 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

46,480 |

40,685 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

23,208 |

57.0% |

| African American |

14,323 |

35.2% |

| American Indian |

99 |

0.2% |

| Asian |

245 |

0.6% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

8 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

1,025 |

2.5% |

| Two or More Races |

1,777 |

4.4% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

1,771 |

4.4% |

| Population Density |

45.1 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$39,962 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$22,750 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

24.3% |

|

Mississippi County, in the northeastern corner of the state, is named for the river that forms its eastern boundary. It is noted for its agricultural production (especially cotton, soybeans, rice, and corn), which has contributed greatly to the economy of the area and the state. Eight steel-related industries have located in the county in recent years, making it the largest steel-producing county in the nation. These and other industries have chosen Mississippi County because of its transportation system that combines river, rail, and interstate highway movement.

Pre-European Exploration

Mississippi County was home to many prehistoric cultures. About 800 known archeological sites exist in the county. Numerous Indian mounds can be seen throughout the county, and many artifacts of the Nodena phase (AD 1400–1650) are on display at the Hampson Archeological Museum State Park in Wilson. The Sherman Mound is one of the best-preserved Central Mississippian sites in the country.

European Exploration and Settlement

Hernando de Soto’s path after he crossed the Mississippi River in 1541 is not precisely known, but it is believed that he visited parts of Mississippi County. It is thought that Father Jacques Marquette visited during his 1673 expedition on the Mississippi River. In 1682, French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, would also have viewed the territory. It was many years before the area began to attract European settlers, as the terrain was primarily swamp land. The land was prone to flooding, and travel was complicated by the many lakes and the heavy growth of mixed hardwood forests. The few settlements adjacent to the rivers, streams, and bayous were peopled by hunters and trappers who traded with the French from Arkansas Post (Arkansas County).

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The population of the county continued to be sparse through the beginning of the 1800s. The advent of the steamboat in the early 1800s led to a slight increase in the white population, as more settlers came in to cut cordwood to supply the steam-driven river traffic. Further population growth was slowed, if not stopped completely, by the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812, which created the “sunk lands” caused by water rushing into the depressions left by the force of the quakes.

The present Mississippi County was created on November 1, 1833, though some border changes occurred later, most notably when Craighead County was created in 1859. By the time of Arkansas statehood in 1836, the county’s population had grown slightly, and more land had been cleared for farming. The Indian population was gradually displaced, moving west toward Big Lake. The western part of the county included the Buffalo Island area and was separated from the eastern part by Big Lake and the Little River. The isolation of this part of the county made it a popular place for outlaws and other unsavory characters to live. These criminals included John Murrell, convicted of slave stealing and suspected of other offenses.

The 1840 census showed 900 whites and 510 slaves for a total of 1,410. Osceola was named the county seat in 1833 and was first incorporated in 1843. Other early settlements and towns were Barfield, Chickasawba (later incorporated into Blytheville), and Elmot (now Luxora). Some local farmers built modest levees to protect their crops, but overflow from the Mississippi and other rivers continued to be a problem. The federal Swamp Land Act of 1850 granted swamp and overflowed land to the state for it to sell. Proceeds from the sales would go to the building of levees and drains. Mississippi County has the largest amount of swamp and overflowed land of any of the other counties included in the surveyor general’s report in 1852.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The 1860 census listed only 3,895 inhabitants in the county, with 1,461 of them being enslaved. By that time, there were several large plantations, mostly in the southern part of the county near the Mississippi River. Prominent were those of the MacGavock, Grider, Driver, and Fletcher families.

As Arkansas seceded from the Union, several companies of soldiers were formed and left the county to serve with the Confederate forces in other areas. There were raids from Union troops in Missouri, and Union troops from Fort Pillow came across the river to Osceola and tore down houses for building supplies. The most notable action was the naval Battle of Fort Pillow on May 10, 1862, in which Confederate River Defense Fleet ships defending Fort Pillow across the river in Tennessee battled Union ships coming up from Memphis. Other military actions in the county included skirmishes at Little River, Pemiscot Bayou, and Osceola, as well as the Big Lake Expedition.

Reconstruction was tumultuous in the area. There was a Freedmen’s Bureau office in Osceola, but Mississippi County was one of ten Arkansas counties initially placed under martial law due to the activity of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). A regiment of the state militia was sent in to keep order. Neither white nor Black citizens felt secure.

The Black Hawk War in 1872 was a series of confrontations involving the Klan and former slaves. In one fatal confrontation in Osceola, African Americans were attacked by white residents and Klan members. Sheriff J. B. Murray was killed by a white judge, Charles Fitzpatrick, who was an appointee of the governor. The judge was arrested, bound over for the next term of court, and released. He escaped across the river and was not brought to justice. A number of Black residents were killed during these years of disturbance, and many simply left the county.

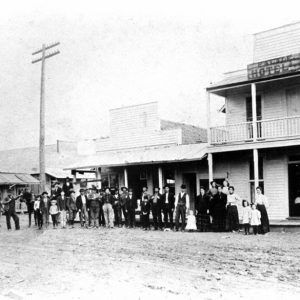

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

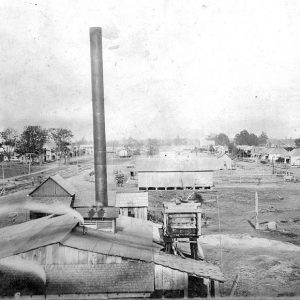

As the state settled down after the war and Reconstruction, the timber and lumber boom began. The virgin forests of Mississippi and other Arkansas counties attracted the attention of Northern companies. One source says that thirty-five sawmills existed in the county in 1902. The larger shipped lumber by river barge to their Northern retail lumber yards. The coming of the railroad in about 1900 accelerated the pace of lumbering. Paralleling the lumber boom was the all-important drainage issue. In 1893, state efforts took the form of establishing drainage districts.

In addition to the already incorporated Osceola, Blytheville was incorporated in 1892; Manila, first settled in 1868, was incorporated in 1901; and Leachville was incorporated in 1916.

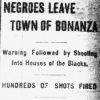

Multiple incidences of racial violence took place in the county in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. John Randolph lost his life in 1875 to a group of white men after allegedly killing and robbing Frank Williams, a white man. Will Caldwell and John Thomas were lynched after allegedly killing a white woman in 1895. Other lynchings took place in 1897, 1899, 1921, and 1926.

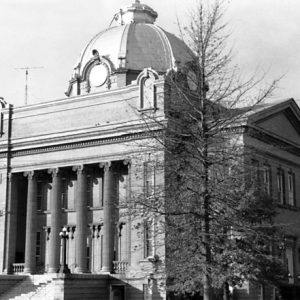

Early Twentieth Century

In 1900, it became apparent that a second county court was needed. In a hotly contested election, Blytheville won out over Manila as the location for a new court, and in 1901, the Chickasawba District was created. By 1902, there was a movement to begin building levees and digging drainage ditches in the county. There was a lot of opposition to drainage plans, but in the end the proponents of drainage prevailed. The push for draining more and more of the land even spelled the end of the short-lived Walker Lake Refuge, which was the state’s first national game preserve; in existence from 1913 to 1926, the refuge was established as a breeding ground for native birds.

The lumber boom continued until the 1920s. The western part of the county became more accessible when the Jonesboro, Lake City and Eastern Railroad Company bridged Big Lake and continued to Blytheville in 1902. One of the first lumbermen was Robert E. Lee Wilson. He purchased a controlling interest in the Jonesboro, Lake City and Eastern Railroad Company. He saw the value of the cleared land and by the time of his death in 1933 had amassed 65,000 acres of farm land.

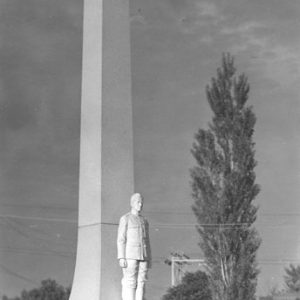

The county provided its share of manpower to the armed forces in World War I, including Manila’s Herman Davis, who is honored by a state park in Manila. Another county hero of World War I was John McGavock Grider of the Sans Souci plantation in the southern part of the county. He is credited with writing, anonymously, War Birds: Diary of an Unknown Aviator.

Agriculture became the economic leader after timber lessened in importance. Much of the cleared land was still very rough, and crops were planted in and around stumps, which made tilling difficult until the stumps were removed. Sharecroppers and tenant farmers shared the human labor. The Depression hit both landlords and tenants hard. One plantation that was purchasing its land from a lumber company paid off its mortgage with bales of cotton. Many others were foreclosed on and lost their land.

However, a boom in duck hunting and fishing occurred in and around Big Lake, which featured many private sporting clubs for “gentlemen hunters.” Railroads advertised package deals. There were also “market” sportsmen who made their living by big volume kills of ducks and fish. The Big Lake National Wildlife Refuge was established by President Woodrow Wilson in 1915. Conflicts over the hunting rights in the area led to the Big Lake Wars as local residents opposed hunting by visitors.

In spite of the earlier drainage initiatives, the county was not spared in the 1927 or 1937 floods. Many in the western parts of the county were evacuated in 1927. In 1937, the Red Cross sent many refugees to Tennessee for the duration of the emergency. The Depression led to many changes in the agricultural economy. The federal Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 mandated the plowing up of cotton acreage to decrease the surplus that was driving the price of cotton to record lows. In 1934, Arkansas’s Federal Emergency Relief Agency (FERA) head, William R. Dyess, acquired 17,500 acres of land in the county and founded what was eventually called the Dyess Colony. A new town was built; families were moved in from other areas and settled on farms of twenty to forty acres. However, this experiment in a cooperative community gradually faded during the World War II years.

World War II through the Faubus Era

Blytheville was home to an Army Air Corps advanced flying school training base during World War II. It was deactivated in 1945 and, in 1955, became the nucleus of Eaker Air Force Base, a part of the Air Force Tactical Air Command. There were German prisoner-of-war camps in the county during World War II. Installations at Bassett, Blytheville, Luxora, and Osceola housed Afrika Corps POWs. The prisoners worked primarily in the cotton fields, chopping, picking, and pulling “baumwolle” (tree wool). County resident Edgar Harold Lloyd of Yarbro received a Medal of Honor posthumously for his bravery against the Germans in France.

The increased mechanization of farm processes led to an increase in migration out of the county during and after World War II. Statistics show that, between 1950 and 1960, the county lost 10,833 white residents and 1,386 Black residents. Many left by way of the Greyhound Bus Lines. One of the few remaining Greyhound bus stations of this era is in Blytheville, a property on the National Register of Historic Places has been restored to its original condition.

Modern Era

Racial unrest in Blytheville led to boycotts and violence in 1970 and 1971. The efforts of the boycott and other actions eventually led to the complete desegregation of the public schools in the town.

Once the world’s largest producer of rain-grown cotton, Mississippi County is still known for its agricultural production. Cotton, soybeans, rice, and corn are the major crops. However, manufacturing is also a presence. American Greetings in Osceola was one of the early manufacturers. Nucor-Yamato and Nucor-Hickman steel companies east of Blytheville, Cyro and Denso in Osceola, and other plants have employed significant numbers of county residents.

Mississippi County Community College (MCCC) in Blytheville opened in 1974 and was the home of a solar power experiment. Now Arkansas Northeastern College (ANC), it is a two-year institution that has incorporated what was the Cotton Bowl Technical Institute in Burdette. ANC has satellite locations in four other cities.

Eaker Air Force Base closed in 1992. Its closure was a major blow to the economy and population of the area. The former base is owned by the City of Blytheville began housing the Arkansas Aeroplex (a complex of private businesses), Westminster Village retirement community, and a sports complex that includes baseball and softball fields and Thunder Bayou Golf Links. It is also home to the Blytheville Station of the Arkansas Archeological Survey.

Among the incorporated communities in the early twenty-first century are Etowah, Joiner, Keiser, Gosnell, Birdsong, Marie, Victoria, and Dell. Unincorporated communities include Tomato and Milligan Ridge.

Famous residents of the county include Charles Kemmons Wilson, founder of Holiday Inn; actress Dale Evans; and actor George Hamilton.

In October 2022, Entergy announced plans to build Arkansas’s largest solar facility, covering 2,100 acres south of Osceola. The facility will provide energy for U.S. Steel operations in the county.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Northeast Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Company, 1889.

Mississippi County, Arkansas: Through the Years. Osceola, AR: Osceola–South Mississippi County Arkansas Historical Heritage Documentation Committee, 1986.

Moreau, Andrew. “Entergy Solar Project Will Be State’s Largest.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 5, 2022, 1D, 4D. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/oct/05/entergy-solar-project-will-be-states-largest/ (accessed October 5, 2022).

Snowden, Deanna, ed. Mississippi County, Arkansas: Appreciating the Past; Anticipating the Future. Little Rock: August House, 1986.

Stern, Scott W. There Is a Deep Brooding in Arkansas: The Rape Trials That Sustained Jim Crow, and the People Who Fought It, from Thurgood Marshall to Maya Angelou. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2025.

Strange, Lonnie R. “The Civil War and Reconstruction in Mississippi County: The Story of Sans Souci Plantation.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2016. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1694/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

———. “The Civil War and Reconstruction in Mississippi County, Arkansas: The Story of Sans Souci Plantation.” Delta Historical Review (2011): 5–76.

Ruth C. Hale

Burdette, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.