calsfoundation@cals.org

Supreme Court of Arkansas

aka: Arkansas Supreme Court

The jurisdiction and power of the Arkansas Supreme Court is controlled by Article VII, Section 4 of the Arkansas constitution as amended in 2000 by Amendment 80. Under this section, the Arkansas Supreme Court generally has only appellate jurisdiction, meaning it typically hears cases that are appealed from trial courts. The Arkansas Supreme Court also has general superintending control over all inferior courts of law and equity.

The Arkansas Supreme Court’s jurisdiction includes all appeals involving the interpretation or construction of the state constitution; criminal appeals in which the death penalty or life imprisonment has been imposed; petitions relating to the actions of state, county, or municipal officials or circuit courts; appeals pertaining to election matters; appeals involving attorney or judicial discipline; second or subsequent appeals; and matters required by law to be heard by the court.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

With the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, Arkansas, as a part of the District of Louisiana, was attached to the territory of Indiana for judicial purposes. Initially, American post commandants—the military officers in charge in locations such as Arkansas Post—continued the colonial practice of military supervision of local legal matters, which had begun during French possession of the area in 1731. In 1804, Indiana territorial governor William Henry Harrison and territorial judges Thomas Terry Davis, John Griffin, and Henry Vandenberg held court in the district capital of St. Louis, Missouri, and enacted laws for the region. The following year, the name of the district was changed to the territory of Louisiana, and President Thomas Jefferson made three judicial appointments to the Superior Court: John B. C. Lucas, Return Jonathan Meigs Jr., and Rufus Easton.

An 1806 act of the territorial legislature created the District of Arkansas. Following the admission of the state of Louisiana to the Union in 1812, Arkansas remained a district of the newly named Missouri Territory, and the Superior Court retained its jurisdiction. On March 2, 1819, President James Monroe approved a congressional act that established a separate territory of Arkansas and, two days later, appointed three judges—Charles Jouett, Robert Letcher, and Andrew Scott—to the Arkansas Superior Court, the immediate predecessor to the Arkansas Supreme Court. (Congress added a fourth position in 1828.) Jouett and Letcher never arrived in Arkansas to exercise their positions. Jouett, according to records from the time, was “driven from the territory by a swarm of mosquitos” while in transit, and Letcher may never have attempted the journey at all. John Thompson, appointed to fill the position vacated by Jouett, turned back en route, reportedly because of rumors of rampant illness in Arkansas. Scott served as sole member of the Superior Court for a year and a half, before Benjamin Johnson and Joseph Seldon finally accepted appointments to join Scott.

The first sessions were held at Arkansas Post (Arkansas County) in November 1819 and January 1820. Scott’s first decision concerned defendant Thomas Dickinson, who was accused of the crime of rape. Finding Dickinson guilty, Scott ordered that the defendant be castrated. The sentence was never completed, though, because territorial governor James Miller pardoned Dickinson. Moving with the territorial capital, the court convened in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in June 1821, reportedly first sitting at a Baptist meeting house. In the summer of 1824, Scott and Seldon fought a duel in which Seldon was killed. Dueling was illegal in Arkansas Territory, but Scott was never prosecuted because the duel was fought in Mississippi, across the river from Helena (Phillips County).

When Arkansas was admitted to the Union in 1836, the territorial Superior Court gave way to a new judicial body. Article VI, Section 1, of the Arkansas constitution of 1836 vested the judicial power of the state “in one Supreme Court, in Circuit Courts, in County Courts and in Justices of the Peace.” Section 2 declared that the Supreme Court would consist of three judges, including a chief justice who would “have appellate jurisdiction only.”

The first three justices of the Arkansas Supreme Court were Chief Justice Daniel Ringo and Associate Justices Townsend Dickinson and Thomas J. Lacy. Herndon Haralson served as the first clerk of the court, while the colorful Albert Pike was the first reporter of decisions. The first written decisions published by the court—the cases of Ezekiel George v. State and Chas. M. Hudspeth v. State—were appeals of indictments for operating houses of gambling.

In 1842, the Supreme Court acted to support the trustees of the Arkansas Real Estate Bank against efforts by Governor Archibald Yell and others to resolve the financial crisis involving both state banks. When Governor Yell asked the court to reconsider its decision, it refused on the grounds that to reconsider a case at the request of the governor would mean losing its independence as a separate branch of government.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

When Arkansas seceded from the Union in 1861, the composition of the Supreme Court remained unchanged. Chief Justice Elbert H. English (a former reporter of decisions), Associate Justice Hulbert F. Fairchild, and Associate Justice Freeman Compton continued in office. As Union troops moved toward Little Rock in September 1863, the Supreme Court, along with other state governmental entities, relocated to Washington (Hempstead County). The court’s records were transported to the new Confederate state capital in Washington. Fairchild, whose family resided in distant Batesville (Independence County), resigned and was replaced by Albert Pike. After the Civil War ended in 1865, a reconstituted Supreme Court resumed its work in Little Rock.

The Reconstruction constitution of 1868 added two justices, an expansion later negated by the constitution of 1874—with, however, the provision that when the population of the state should “amount to one million, the General Assembly may, if deemed necessary, increase the number of judges of the Supreme Court to five.” At the end of the next decade, the legislature, in Act 19 of 1889, authorized a total of five justices.

In 1873, the Supreme Court refused to order an examination of the 1872 governor’s election, saying it had no jurisdiction over the results of such a race. This refusal to act was one of the factors that led to the Brooks-Baxter War the following year. In 1877, the Supreme Court declared in State of Arkansas v. Little Rock, Mississippi River and Texas Railway Company that that year’s railroad aid bonds were unconstitutional because they were sold before ninety days had passed since the end of the legislative session, a delay required by state law.

Early Twentieth Century through World War II

By 1904, the court had become so backlogged with cases that it was three years behind the docket. The Arkansas State Bar Association gave unofficial support to younger candidates for the court, breaking with the tradition that permitted judges to be reelected to the court without significant opposition. The younger court committed itself to dealing with fifteen cases each week, with three opinions to be written weekly by each judge. Working twelve to fifteen hours a day, the judges had caught up to current cases by the end of 1910. Constitutional sanction of the enlargement of the court came in 1924 with voter approval of Amendment 9, which also allowed for the future legislative creation of two additional judgeships. Act 205 of 1925 further increased the number of justices to seven. No further expansion in the court’s size has occurred since 1925.

Beginning in 1906, with Rice v. Palmer, the Supreme Court became involved in the popular movement to allow laws, including amendments to the state’s constitution, to be shaped by referenda. The court ruled that only three such referenda could be placed on the ballot in any one election; it also ruled that such referenda passed only if they were approved by a majority of voters participating in the election (rather than a majority of voters voting on the referendum). In other words, every voter who took a ballot but did not vote for a referendum was assumed to have voted against it. Among the votes that failed due to this interpretation was the re-creation of the office of lieutenant governor. Although the referendum appeared to have passed by a vote of 46,567 to 45,206, the court’s ruling declared that it had not passed, because only 46,567 of the 145,511 people participating in that election had voted for it. The general principle was overturned in 1925 in Brickhouse v. Hill, a case that the justices disqualified themselves from hearing, leading Governor Thomas Terral to appoint a special court of five judges to hear this one case. The Brickhouse decision was specifically applied to the office of lieutenant governor in 1926 in Combs v. Gray.

The Supreme Court ruled in 1929 that the Democratic Party was a private organization and therefore could make its own rules about who was allowed to be a member of the party. This decision allowed white-only primaries, which continued in Arkansas until the 1940s. In 1935, the Supreme Court upheld the two-percent state sales tax enacted by the legislature to support public schools. The court in 1942 heard a case (Lynch v. Hammock) involving a doctor from Tennessee hired to work at the Rohwer Relocation Center, an internment camp holding Japanese American citizens from the West Coast. The court ruled that the state had no jurisdiction to forbid the doctor from working in Arkansas, even though he was not licensed in Arkansas, on the grounds that he was working on federal property. Camp officials protested the ruling, even though it was in their favor, fearing that the same logic would be used by state agencies to refuse needed services for the camp.

Faubus Era through the Modern Era

The court became involved with the desegregation crisis in Little Rock when it heard Garrett v. Faubus in 1959. By a narrow vote, the court upheld Act 4, which had given the governor authority to close schools when he felt that they were threatened by violence. In 1967, in State v. Epperson, an appeal to Epperson v. McDonald (1966), the court heard challenges to Act 1 of 1928, which forbade the teaching of the theory of evolution in state schools. The court upheld the act, but the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the decision the next year, criticizing the Arkansas Supreme Court for its reluctance to challenge public opinion and for not handling the case in a thorough and complete manner.

By the 1970s, the Arkansas Supreme Court’s caseload had become so burdensome that a second appellate court was deemed necessary. Amendment 58, approved by voters in 1978, empowered the General Assembly to establish a court of appeals “subject to the general superintending control of the Supreme Court.” Act 208 of 1979 created the appellate court and provided for six judges to be elected from districts across the state. In Act 1085 of 1993, the legislature provided for the doubling of the number of appellate court judges to twelve.

The Arkansas Supreme Court in 1983 heard the case Dupree v. Alma School District No. 30 and determined that the state’s method of funding public education was unconstitutional. Rejecting local control as an excuse for disparities in funding and in educational opportunities in the state’s school systems, the court demanded that Arkansas revise its funding statutes. The issue was visited again in 2002 in Lake View School Dist. No. 25 v. Huckabee. The court again ruled the state’s school funding system unconstitutional, giving a deadline of January 1, 2004, to fix the problem. The state missed the deadline; after further court measures set a new deadline of December 2006, the legislature met in special session and found ways to increase funding of public schools and to consolidate school districts in order to meet the court-demanded requirements.

Meanwhile, in 1993, the court heard a suit against Walmart Inc. claiming that its pricing practices were unfair to smaller pharmacies. The court ruled in favor of Walmart Inc. In Jegley v. Picado, heard in 2002, the court declared Arkansas’s sodomy statute unconstitutional, thus removing the last laws that identified homosexual behavior as criminal.

The first woman to serve as an Arkansas Supreme Court justice was Elsijane Trimble Roy, who was appointed in 1975. George Howard Jr. became the first African-American justice in 1977. Both Roy and Howard were later appointed to the federal bench, and both died in 2007. The court had a female majority for the first time after new justice Rhonda Wood was sworn in on January 6, 2015.

The longest-serving justice was George Rose Smith, who served from 1949 to 1987. When Smith first joined the court in 1949, he joined Chief Justice Griffin Smith and Associate Justice Frank G. Smith in an unprecedented trio of judges on the same state Supreme Court bearing the same last name. Justice George Rose Smith was a man of many diverse talents who created crossword puzzles for the New York Times and was proficient in woodworking and in bricklaying. He was celebrated for his incisive style and his mischievous wit. Smith once offered $100 to anyone who could find a grammatical error in any of his written opinions, an award he never had to pay. For two years, he wrote and published, as April Fools’ pranks, cases and opinions that were entirely invented. One of these imaginary cases, Catt v. State (1985), involved brothers, Kilkenny Catt and Gallico Catt, who received inconsistent jury verdicts for identical acts of fraud and cocaine possession. Not only were these articles taken seriously by other Arkansas law scholars, but the Catt case was even quoted in a decision by a court in Delaware before the joke was exposed.

For additional information:

Arkansas Judiciary. https://www.arcourts.gov/ (accessed August 23, 2022).

Dumas, Ernest. “The Last Word in Justice.” Arkansas Times, December 23, 1994, pp. 14–16.

Kincaid, Sydney. “Amendment 80 and the Effects on Arkansas Supreme Court Elections.” BA honors thesis, University of Arkansas, 2024. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/plscuht/33/ (accessed September 6, 2024).

Ledbetter, Calvin Reville, Jr. “The Arkansas Supreme Court: 1958–1959.” PhD diss., Northwestern University, 1961.

Looney, J. W. Distinguishing the Righteous from the Roguish: The Arkansas Supreme Court, 1836–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2016.

Looney, Jerry Wayne. “‘A Stronghold of Southern Legal Puritanism’: The Arkansas Supreme Court and the Development of Criminal Law and Procedure, 1836–1874.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2010.

Sharum, Jerald A. “Arkansas’s Tradition of Popular Constitutional Activism and the Ascendancy of the Arkansas Supreme Court.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review 32 (Fall 2009): 33–105.

Stafford, L. Scott. “The Arkansas Supreme Court and the Aftermath of the Civil War.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review 23, no. 2 (2001): 355–407. Online at https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview/vol23/iss2/2 (accessed August 23, 2022).

———. “Slavery and the Arkansas Supreme Court.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review 19 (Spring 1997): 424–439.

Stafford, Logan Scott. “The Arkansas Supreme Court and the Civil War.” Journal of Southern Legal History 37 (1999): 37–114. Online at https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/faculty_scholarship/215/ (accessed October 17, 2022).

———. “Judicial Coup D’état: Mandamus, Quo Warranto and the Original Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of Arkansas” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review 20, no. 4 (1998): 891–984. Online at https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview/vol20/iss4/3/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

Stevenson, C. R. Arkansas Territory—State and its Highest Courts. Little Rock: Clerk of the Supreme Court, 1946.

Wood, Rhonda, Jessica Finan Patterson, and Brian W. Johnson. “What It Takes: A Statistical Analysis of Arkansas Supreme Court’s Petition for Review Process.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review 44 (Spring 2022): 491–530. Online at https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview/vol44/iss4/2/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

Wright, Robert R. Old Seeds in the New Land: History and Reminiscences of the Bar of Arkansas. Fayetteville, AR: M. & M. Press, 2001.

William B. Jones Jr.

Bottle Imp Archives, Little Rock

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Adkisson, Richard B.

Adkisson, Richard B. Alderson, Edwin Boyd Jr.

Alderson, Edwin Boyd Jr. Arkansas Court of Appeals

Arkansas Court of Appeals Arnold, William Howard "Dub"

Arnold, William Howard "Dub" Baker, Basil

Baker, Basil Battle, Burrill Bunn

Battle, Burrill Bunn Bowen, Thomas Meade

Bowen, Thomas Meade Brill, Howard Walter

Brill, Howard Walter Brown, Lyle

Brown, Lyle Brown, Robert Laidlaw (Bob)

Brown, Robert Laidlaw (Bob) Bunn, Henry Gaston

Bunn, Henry Gaston Butler, Turner

Butler, Turner Byrd, Conley F

Byrd, Conley F City of Hot Springs v. Creviston

City of Hot Springs v. Creviston Clendenin, John J.

Clendenin, John J. Cockrill, Sterling Robertson

Cockrill, Sterling Robertson Corbin, Donald Louis

Corbin, Donald Louis Dickey, Betty

Dickey, Betty Dudley, Robert Hamilton (Bob)

Dudley, Robert Hamilton (Bob) Glaze, Thomas Arthur (Tom)

Glaze, Thomas Arthur (Tom) Gunter, James Houston (Jim), Jr.

Gunter, James Houston (Jim), Jr. Hannah, James Robert (Jim)

Hannah, James Robert (Jim) Hart, Jesse Cleveland

Hart, Jesse Cleveland Hemingway, Wilson Edwin

Hemingway, Wilson Edwin Hickman, Darrell David

Hickman, Darrell David Holt, Jack Wilson, Jr.

Holt, Jack Wilson, Jr. Holt, Joseph Frank

Holt, Joseph Frank Hoofman, Clifton Howard (Cliff)

Hoofman, Clifton Howard (Cliff) Jesson, Bradley Dean

Jesson, Bradley Dean Law

Law Mansfield, William Walker

Mansfield, William Walker Mays, Richard Leon

Mays, Richard Leon McHaney, Edgar Lafayette

McHaney, Edgar Lafayette Newbern, William David

Newbern, William David Politics and Government

Politics and Government Purtle, John Ingram

Purtle, John Ingram Scott, Christopher Columbus

Scott, Christopher Columbus Selden, Joseph

Selden, Joseph Sheffield, Ronald Lee

Sheffield, Ronald Lee Smith, Lavenski Roy

Smith, Lavenski Roy State v. Buzzard

State v. Buzzard Thornton, Raymond Hoyt (Ray), Jr.

Thornton, Raymond Hoyt (Ray), Jr. Tuck, Annabelle Davis Clinton Imber

Tuck, Annabelle Davis Clinton Imber Ward, John Paul

Ward, John Paul Watkins, George Claibourne

Watkins, George Claibourne Wood, Carroll D.

Wood, Carroll D. Wright v. Arkansas

Wright v. Arkansas Arkansas Supreme Court

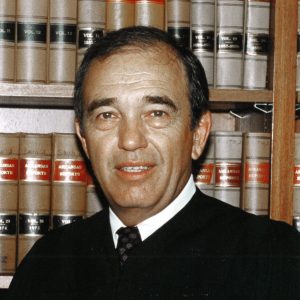

Arkansas Supreme Court  W. H. "Dub" Arnold

W. H. "Dub" Arnold  Howard W. Brill

Howard W. Brill  Turner Butler

Turner Butler  Donald L. Corbin

Donald L. Corbin  Edward Cross

Edward Cross  Robert H. Dudley

Robert H. Dudley  Elbert English

Elbert English  Susan Epperson

Susan Epperson  Gay and Lesbian Movement Press Conference

Gay and Lesbian Movement Press Conference  James H. Gunter

James H. Gunter  James R. Hannah

James R. Hannah  Jo Hart

Jo Hart  Darrell D. Hickman

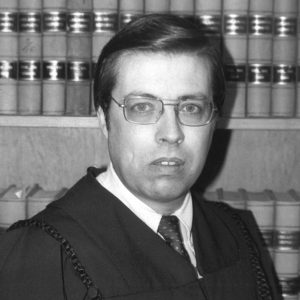

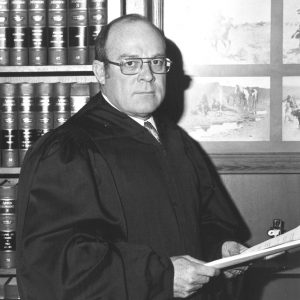

Darrell D. Hickman  Jack W. Holt

Jack W. Holt  Jack Wilson Holt Jr.

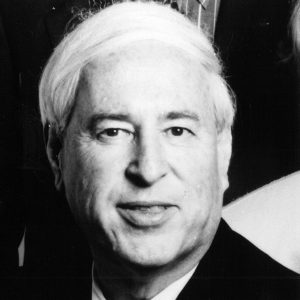

Jack Wilson Holt Jr.  Brad Jesson

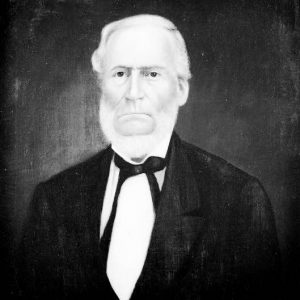

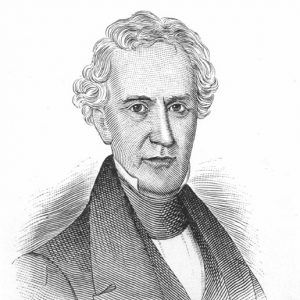

Brad Jesson  Benjamin Johnson

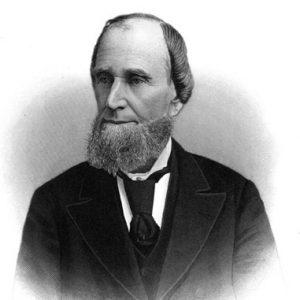

Benjamin Johnson  William Kirby

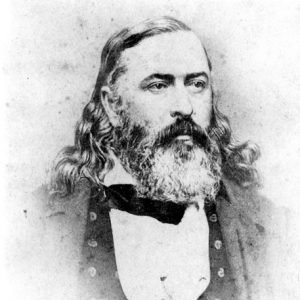

William Kirby  Albert Pike

Albert Pike  John I. Purtle

John I. Purtle  John I. Purtle

John I. Purtle  Andree Roaf

Andree Roaf  Andrew Scott

Andrew Scott  Supreme Court Building

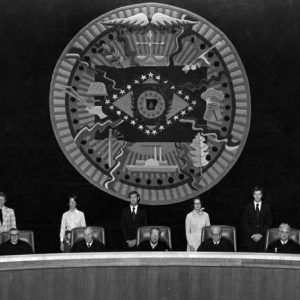

Supreme Court Building  Supreme Court Members

Supreme Court Members  Supreme Court of Arkansas, 1942

Supreme Court of Arkansas, 1942  Supreme Court of Arkansas, 1950

Supreme Court of Arkansas, 1950  Joyce Warren at Supreme Court

Joyce Warren at Supreme Court

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.