calsfoundation@cals.org

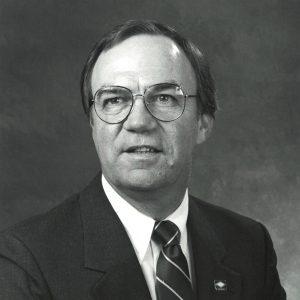

Clifton Howard (Cliff) Hoofman

Clifton Howard (Cliff) Hoofman, who was reared by grandparents on tenant farms in White County, became a lawyer and politician and held constitutional offices in all three branches of state government. He served in the Arkansas House of Representatives for eight years, the Arkansas Senate for twenty years, four years as a state highway commissioner, and two years on the Arkansas Supreme Court; he also had two separate sojourns of two years each on the Arkansas Court of Appeals. As a close friend and ally of two governors, Bill Clinton and Mike Beebe, Hoofman was instrumental in passing much of the major legislation enacted during their combined twenty years in the governor’s office.

Cliff Hoofman was born on June 23, 1943, at the home of his parents in the Plainview (White County) community north of Searcy (White County) and Judsonia (White County). His parents, Joseph Eli Hoofman, who was a shoe cobbler, and Agnes West Hoofman, had four sons, two older than Cliff. One suffered from nephritis and died as a youth.

The family moved to California when Hoofman was an infant. His parents separated when he was two, and his mother returned to White County with Hoofman and his brothers. Subsequently, she married Wesley Lewis and moved to Judsonia. His eldest brother, J. W. (Joseph William), went to live with their maternal grandparents, J. W. and Clara West, who were tenant farmers in the nearby community of Honey Hill. When his brother went to California and enlisted in the U.S. Army, Cliff, then about nine, took his place at the farm to help the feeble couple. He quickly picked up farm chores and hunted squirrels, rabbits, and opossums for the table. They moved from one vacant house to another in the community. The houses had no electricity, gas, or running water, and he and his grandfather hitched rides into Searcy. His grandmother kept the family’s holdings in a cloth bag pinned inside her blouse. He rode a bus to school in town. Hoofman believed that his grandfather had been a somewhat successful farmer at one time but never recovered after losing everything in the Great Depression.

Throughout high school, Hoofman worked at many jobs to support himself and assist his family and to pay for college. He dropped out of school in the eleventh grade and went to work at a gas station, but two school officials persuaded him to return to school for half days under the diversified education program and work afternoons as a clerk at a dry-goods store. He worked as a salesman at clothing stores in Searcy, delivered freight for the Missouri Pacific railroad, and worked summers for a pipeline construction company or a pea-canning company in eastern states.

Hoofman credited the two educators who talked him into returning to high school with all his success. He took an interest in learning for the first time, and it impelled him to go to college. He married Carole Merritt of North Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1965, and she taught school in her hometown while he finished college.

He graduated from what is now the University of Central Arkansas in Conway (Faulkner County) in 1968 and then went to law school at the Little Rock Law School at night. He graduated from the University of Arkansas School of Law in Fayetteville (Washington County) in 1972 after taking a summer course there in order to have enough credits to graduate and take the state bar exam in late summer.

At the bar exam, he met Mike Beebe of Newport (Jackson County), and their careers began to intertwine. Beebe joined the leading law firm in Searcy and Hoofman a struggling firm in Little Rock. They soon faced each other in court, Hoofman representing “a poor old couple” and Beebe the insurance company. Circuit Judge Elmo Taylor, famous for favoring hometown lawyers, awarded the verdict to Beebe, an early lesson in Arkansas jurisprudence for Hoofman. But the two became friends and discussed their cases almost weekly by telephone.

Hoofman was appointed assistant city attorney of North Little Rock, a part-time job, within a few months of getting his law license, and soon the mayor appointed him city attorney. He became legislative chairman for the United Transportation Union in Arkansas.

In 1974, nearly two years out of law school, he ran for a seat in the House of Representatives from North Little Rock and defeated two-term state representative Bob Traylor. He won all his races handily after that, three for the House and five for the Senate. He would later say of his twenty-eight years in the legislature that his rosy illusions about legislating as a civic exercise for the common good were destroyed very early in his career. Passing laws was a daily exercise in navigating the competing influences of special corporate interests. Among his achievements, besides school and highway legislation, was a constitutional amendment ending ad-valorem taxation of household furnishings and passage of a $20 million state appropriation to help build an entertainment arena (now Simmons Bank Arena) in his North Little Rock district.

Hoofman developed a close friendship with Henry C. Gray, the longtime head of the Arkansas Department of Transportation, and he became a lifetime champion of highways. He led all the battles to raise taxes for highways and, notably, to place a heavier burden on the transportation industry to pay for road and bridge maintenance. In 1981, he blocked legislation sought by the trucking industry and major shippers such as Tyson Foods and Riceland Foods to raise the weight limit on Arkansas highways from 73,280 pounds to 80,000 pounds, but they eventually prevailed. But he succeeded in passing a “weight-distance” or “ton-mile” tax on heavy truckloads, assessing them a tax based on the weight of the load and the miles traveled across Arkansas. Hoofman maintained that shippers and big trucks accounted for three-fourths of the cost of maintaining highways and bridges but paid for less than a fourth of it, leaving the burden to motorists through gasoline taxes and vehicle licenses. He was dismayed in 1991 when his friend Bill Clinton, who planned to run for president in 1992 and needed to placate the national trucking industry, had the truck-weight tax repealed and substituted an increase in fuel taxes that landed on motorists. Hoofman had been Clinton’s floor leader in the Senate for most of the 1980s, including legislative sessions in 1983 and 1985 that produced the education and economic-development initiatives that made him a national figure.

Hoofman and Mike Beebe were elected to the Senate the same year, 1982, and became allies; they both retired from the Senate in 2002, as term limits law barred them from running again. Beebe was elected attorney general that year. While Hoofman was the attorney general’s liaison with the legislature, he helped Beebe guide the legislature through controversial education reforms, including higher taxes, school consolidation, and state funding of school capital improvements. Beebe addressed both houses of the legislature, most of them former colleagues of Hoofman and the attorney general, about the requirements of the constitution and the need to satisfy the orders of the state Supreme Court. As governor in 2007, and with Hoofman as his chief legislative liaison, Beebe signed legislation mandating that the public schools always be fully funded before any other functions of government.

The governor appointed Hoofman to a ten-year term on the Arkansas Highway Commission, a constitutional office, in 2007. He served four years until Beebe appointed him to a vacancy on the Arkansas Court of Appeals. In 2013, Beebe named Hoofman to a seat on the Arkansas Supreme Court when Justice Robert L. Brown retired, and in December 2014, before leaving office, the governor appointed him again to fill a two-year vacancy on the Court of Appeals. That term ended December 31, 2016.

As a Supreme Court justice, Hoofman recused himself from participating in the court’s most contentious case, which judged the validity of a constitutional amendment enacted in 2004 that forbade the marriage of people of the same sex and the state from recognizing such marriages that were performed in other states. The state senator representing Hoofman’s district in Faulkner County had telephoned him and told him of his support for the marriage prohibition. Hoofman told the senator he could not talk to him about it, but when others approached him and said they knew that he and the senator had discussed the case, he decided he was bound to recuse himself to avoid the appearance of any extrajudicial influence. The court then became embroiled in an internal dispute and never decided the appeal. The U.S. Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals formally invalidated the Arkansas law in 2015 by upholding a decision by an Arkansas federal judge, after the U.S. Supreme Court said such state laws violated the equal-protection and commerce clauses of the U.S. Constitution. Hoofman later said that if he had not been recused, he was sure the Arkansas Supreme Court would have ruled on the case before his term ended.

Hoofman and his wife, who had a daughter, divorced in 1993. He bought a small farm near Searcy in 1995 and raised cows there. In 2000, he married Debbie Birch of North Little Rock. He then bought a larger farm near Enola (Faulkner County), built a house there, and began raising mules along with his cows.

For additional information:

Dumas, Ernie. Interview with Cliff Hoofman, January 10, 2017. Arkansas Supreme Court Project. Arkansas Supreme Court Historical Society. https://courts.arkansas.gov/sites/default/files/Cliff%20Hoofman%20Transcript.pdf (accessed September 8, 2017).

Lancaster, Bill. Inside the Arkansas Legislature. Little Rock: Xlibris Corporation, 2015.

Sharkey, Fredricka. “UCA’s Impact Spurs Judge’s Lifetime Support.” UCA Alumni News, Fall 2015.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Law

Law Politics and Government

Politics and Government Cliff Hoofman

Cliff Hoofman

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.