calsfoundation@cals.org

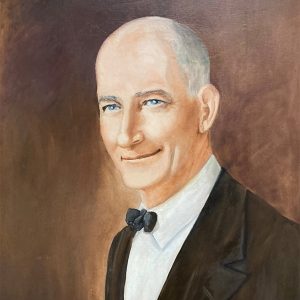

Turner Butler (1869–1938)

Lawyer and jurist Turner Butler was a farmer and schoolteacher before educating himself in law. Butler practiced law for twenty years before being elected a chancery judge. He was a trial judge for fifteen years before he was appointed and then elected to the Arkansas Supreme Court, where he served the last nine years of his life. As a justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1930, he wrote a sublime opinion establishing the precedent that the courts must stand in the way of corporations doing harm to land and streams in the pursuit of private profit or the alleged public good.

Turner Butler was born on July 7, 1869, as Phillip Turner Butler, in the town of Poplar Bluff (Ashley County), which became Parkdale in the 1890s. He dropped the name Phillip and always signed his name Turner Butler. His father, LaVelle Butler, was a Virginian, and his mother, Mary Atkins Butler, was reared in Alabama. They moved to Ashley County before the Civil War, during which LaVelle was a colonel in the Confederate army.

The family moved to Hamburg (Ashley County), where Turner graduated from high school. He taught school, clerked at a country store, and started farming with his childhood and lifetime friend, Percy George. Both men began reading law at Hamburg with M. L. Hawkins, later a circuit and chancery judge, and R. E. Craig. George and Butler got law licenses and formed a partnership at Hamburg.

Butler was elected to the Arkansas House of Representatives from Ashley County in 1894, only months after being admitted to the bar; he served two terms and then was elected to a single term in the Arkansas Senate in 1898.

Butler was elected judge of the Tenth Judicial Circuit in 1914 and was reelected three times. The Supreme Court rarely overturned his decisions. When Justice Carroll D. Wood, who had served continuously since 1893, retired from the Supreme Court in May 1929, Governor Harvey Parnell appointed Judge Butler to finish his term. Butler was elected to a full term on the court in 1932.

Frail, studious, and reclusive, Butler did not marry until he was fifty-five. On June 4, 1925, he married Sallie Chamberlain of Little Rock (Pulaski County). They had no children.

Justice Butler’s most widely cited opinion came in the early environmental case of Meriwether Sand and Gravel v. State, in 1930. The gravel company claimed the right to pollute Bodcaw Creek in the Red River valley of southwestern Arkansas for the larger public good of economic development. Downstream property owners objected. Restraining the company from harvesting gravel from the stream, the company argued, would be a terrible precedent that would discourage economic development across the state.

Butler’s opinion described the effect of the gravel mining in the stream: “The water is no longer limpid and pure, but muddy and turbid, to the extent that fish are unable to live there, and those that reach this stream from below must come to the surface to obtain necessary oxygen, and after a time sink into the water only to die and be cast upon the shore. The pools and lakes in which urchins and grown folks were wont to bathe are now so discolored and befouled by the foreign matter brought from the gravel plant above…that bathing is no longer indulged.”

“Whether the damage to the appellees was great or slight depends largely upon the point of view,” he continued. “In the eyes of those who burrow into the earth for inert and dull ores, whose value lies only in use, it may so appear; but value lies also in something more, and that is valuable, whatever it may be, in proportion as it tends to promote not only a utilitarian purpose, but also contentment and rational pleasure.” He added, “The courts—and it was never intended to be otherwise understood—are not the masons to chisel away vested rights of property of private individuals, however humble and obscure the owner, for the benefit of the public or great corporations.”

The opinion is often cited in environmental litigation as precedent for government action to control land, water, and air pollution.

Justice Butler suffered a liver ailment and died on January 19, 1938, at his home in Little Rock. He was buried at Hamburg. At some later date, his remains were moved to Little Rock’s Roselawn Memorial Park.

His friend Frank Pace of Little Rock, who was later Secretary of the Army under President Harry S. Truman and chief executive of General Dynamics Corporation, penned a tribute to Butler that the Supreme Court published. He said Butler “led a rather lonely life and found the joy of living” in his legal work and in books. “He had a heart that was attuned to the distress of the world,” Pace said. “The Earth’s meek, lowly, and weak were the objects of his solicitude. There was no greed, no avarice, no mania for the accumulation of wealth.” It was reflected, Pace said, in Butler’s court opinions and in all his deliberations on the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Griffin Smith, in a statement the day after Butler’s death, said, “He was interested in the misfortunes of his fellow man, and his solicitude for the so-called underdog was almost proverbial.”

For additional information:

“Justice Turner Butler Passes; Funeral Today.” Arkansas Gazette, January 20, 1938, pp. 1, 6.

Meriwether Sand and Gravel v. State, 181 Ark. 316 (1930).

Pace, Frank. “Celebrating the Life, Character and Public Service of the Late Turner Butler, Associate Justice.” Resolutions and Addresses, Supreme Court of Arkansas, Volume 1938.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Law

Law Politics and Government

Politics and Government Turner Butler

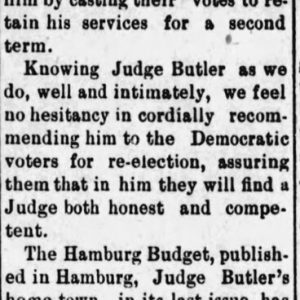

Turner Butler  Turner Butler Candidacy Story

Turner Butler Candidacy Story

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.