calsfoundation@cals.org

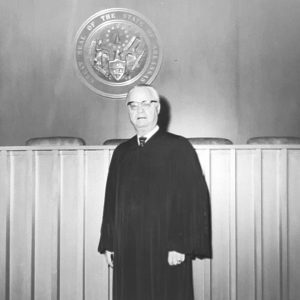

Lyle Brown (1908–1984)

Lyle Brown was a lawyer and historian who capped a career in politics by serving for twenty-one years as a circuit judge and justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court. Brown earned some renown as the only justice on the court at the time to insist on the right of the state’s public schools to teach evolutionary theory. When a legal challenge to the state’s 1928 initiated act that forbade the teaching of evolution reached the Arkansas Supreme Court late in 1966, there was intense pressure for the court to be united in upholding the law, which was widely believed to protect the biblical account of the creation of the universe from perceived scientific attacks. To satisfy two justices who originally dissented, the court agreed not to issue an opinion explaining its stand for the law, but Brown told his colleagues that he would never yield. He wanted to be recorded as dissenting and favoring striking down the law as an impingement upon free speech and the U.S. Constitution’s establishment clause.

Lyle Brown was born on August 10, 1908, in Poplar Bluff, Missouri, the son of Otis Delmar Brown, who was a Union Pacific Railroad worker, and Molly Brown. He won a high school debate contest and then won the regional contest at Southern Methodist University (SMU) in Dallas, Texas. That won him a full scholarship and a stipend to Henderson-Brown College (now Henderson State University), a Methodist college in Arkadelphia (Clark County).

In 1931, he graduated from Henderson Brown, where he was president of the student body, head of the debate team, a cheerleader, and organizer of the college’s first band. He received a master’s degree in history and political science at SMU and eventually completed course work on a doctorate in history at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge; he did not, however, complete his dissertation in time to be awarded the degree. He returned to Henderson Brown as a professor of history and dean of men and also studied law privately, passing the state examination to become a lawyer. He married Glen Vivian Ohls, a Henderson Brown student from the nearby town of Dalark.

Brown launched a political career in 1934 by winning a seat in the Arkansas House of Representatives from Clark County. He served two terms. In 1942, he and his wife moved to Hope (Hempstead County) with their first daughter, and he established a law practice; they had another daughter after the move. He was elected mayor of Hope and to two terms as prosecuting attorney of the Eighth Judicial District. In 1952, he was elected to complete the last two years of the term of a circuit judge who retired. He was reelected three times.

In 1966, he ran for one of four seats on the Arkansas Supreme Court that became vacant that year. When Brown filed for the position, Griffin Smith, a Little Rock (Pulaski County) lawyer who was the son of a former chief justice, withdrew. Brown was the only judge elected without opposition.

On the same day Brown filed, April 1, 1966, a trial in the evolution lawsuit Susan Epperson v. State of Arkansas was held in Pulaski County Chancery Court. The case was widely followed in the expectation that it would be a reprise of the famous “Scopes Monkey Trial” of 1925, in which a Tennessee teacher was found guilty of teaching evolution and violating a state law similar to the one Arkansas adopted in 1928. Judge Murray O. Reed shut off questioning by Attorney General Bruce Bennett and ruled that the law violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which protected citizens from state interference with freedom of speech and thought. A storm of protests followed.

When Brown was sworn in on January 1, 1967, an appeal of the Pulaski County ruling was pending at the Supreme Court. In the court’s private conference, the justices split, with four favoring upholding the law and overturning Judge Reed and three—Justices Brown, George Rose Smith, and J. Fred Jones—favoring invalidating the 1928 law. The controversy over the law was so fierce that the chief justice, Carleton Harris, insisted that the justices be united, and they wrestled with the issue quietly for the next six months. Finally, on the last day of the term, June 5, 1967, the court issued a two-sentence order, unsigned by any justice, saying the 1928 act was a valid exercise of the state’s power and did not abrade the federal or state constitutions. The order merely noted that Justice Brown dissented. A law clerk for Justice Brown later said that the justices had engaged in a furious argument during which Justice Brown tore up his written dissent, flung it across the conference table, and announced that he would be recorded as dissenting even if they held the case for years. Arkansas and Mississippi were the only states remaining at that time with laws barring the discussion of evolution in school classrooms.

Epperson v. Arkansas was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled unanimously in November 1968 that the Arkansas law violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment, which prohibited the state from establishing or recognizing one religion. A subsequent anti-evolution law enacted by the Arkansas General Assembly in 1981 was invalidated by a U.S. district judge in 1982 (McLean v. Arkansas Board of Education), and the decision was not appealed.

Justice Brown also wrote the Supreme Court’s order in another landmark civil-liberties case, Neal v. Still (1970), in which the Supreme Court, by a vote of five to two, struck down a law enacted by the legislature at a special session in 1958 to thwart civil rights activity on school campuses. Joe and Barbara Neal were arrested for distributing antiwar literature and talking to students at Henderson in Arkadelphia and convicted of “causing a disturbance on school property.” Justice Brown wrote: “It is difficult to conceive of language more vague than that which declares one a law violator when he ‘creates’ a disturbance or breach of the peace ‘in any way whatsoever.’ The same is true of language which makes it a misdemeanor to use ‘offensive talk.’ Then we find a prohibition against ‘attempting to intimidate,’ which is about as vague as one can imagine.”

In ill health, Justice Brown retired in 1975 and returned to Hope. He died on May 1, 1984. He is buried in Memory Gardens cemetery in Hope.

For additional information:

“Circuit Judge of Hope Files for High Court; House Race Attracts 4.” Arkansas Gazette, April 1, 1966, p. 1B.

“Judges Party.” New Yorker, August 26, 1967, pp. 20–21.

“Lyle Brown, Former Justice, Dies at Age 75.” Arkansas Gazette, May 2, 1984, p. 9A.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Law

Law World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Lyle Brown

Lyle Brown  Lyle Brown at Desk

Lyle Brown at Desk

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.