calsfoundation@cals.org

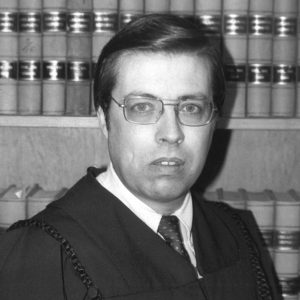

James Robert (Jim) Hannah (1944–2016)

James Robert (Jim) Hannah was a popular jurist who, as chief justice, led the Arkansas Supreme Court through a tumultuous period early in the twenty-first century. Hannah, who was known for his dignity and soft-spoken leadership, spent more than thirty-six years as a trial court judge and Supreme Court justice. When deeply divisive political issues reached the court after his election as chief justice in 2004, however, he could not prevent a fracture among the justices.

Jim Hannah was born on December 26, 1944, at the U.S. Naval Hospital in Long Beach, California, to Frank Alvin Hannah, who was an officer in the U.S. Navy, and Virginia Marie Stine Hannah. His father was stationed in California and Miami, Florida, in the final stages of World War II. After the war, Hannah moved with his parents and his sister to Ozark, Missouri, where his parents were partners in a dry-cleaning business, and later to Harrison (Boone County), where they were partners in a soft-drink bottling company. He was a star basketball and baseball player at both Ozark and Harrison schools and enrolled at Drury College in Springfield, Missouri, on a basketball scholarship. He transferred to the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County), where he received dual degrees in law and accounting in 1968. Hannah was first married to Linda Villines, and they had three children; they later divorced, and he married Pat Johnson, who had two adult children at the time.

He joined a prominent law firm in Searcy (White County), in which one partner was a longtime state senator and another—Mike Beebe—would soon become a state senator and then governor. For the next ten years, he would serve as city attorney for Searcy and six other small towns in the area, as deputy prosecuting attorney for adjoining Woodruff County, and also as a city judge and juvenile judge.

When Dale Bumpers ran for governor in 1970, Hannah was his earliest supporter in the White County area. He became an assistant to Governor Bumpers during legislative sessions and served on the state Board of Pardons and Paroles. They remained lifelong friends.

In 1978, Hannah was elected chancery and probate judge for the Seventeenth Judicial District; he was reelected three times, serving a total of twenty-two years. In 2000, he was elected to be a justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court, and he was elected chief justice in 2004 to succeed Betty Dickey, who had been appointed to complete the term of William H. “Dub” Arnold, who retired in 2003. Over the next ten years, he would gain prestige nationally. He was president of the National Conference of Chief Justices and chairman of the board of directors of the National Center for State Courts.

Around 2000, the court began to field unusually divisive and politically treacherous cases, starting with Lake View School District No. 25 v. Huckabee, which was the culmination of a long legal battle over funding Arkansas public schools. The Lake View case, which originated in 1992 and asserted that the state had not complied with the court’s orders in Jim DuPree v. Alma School District No. 30, had already been before the Supreme Court once and returned for another trial. It arrived before the Supreme Court in 2002, which ruled that the Arkansas General Assembly and the governor had not corrected the shortcomings in school funding and supervision. Two years later, the Supreme Court required another legislative session and still further steps to see that the financial needs of schools were always first in the distribution of state tax funds.

The steps that the court seemed to require, including higher taxes and school consolidation, were unpopular in many quarters, and legislators were resentful. From the conclusion of its work on court-ordered school reforms in 2006 until 2015, the legislature did not raise the salaries of justices, which ordinarily were adjusted every two years like those of other government employees. A constitutional amendment ratified in 2014 handed the duty to fix judicial salaries to an independent commission.

Hannah began making annual State of the Judiciary messages, in which he outlined reforms in court procedures and asserted the importance of the judiciary remaining independent in the face of political and commercial pressure and financing. He streamlined administration of the courts, giving the Arkansas Supreme Court the distinction of being the first in the nation to record all its proceedings electronically—making all its work, including oral arguments, available to the public instantly.

Legislative relations worsened when Hannah’s court twice, in 2009 and 2011, struck down provisions of the state “tort reform” law, Act 649 of 2003, which had limited the extent to which people could collect damages from commercial entities such as manufacturers, retailers, and nursing homes. The act was a major goal of chambers of commerce and industries. The Arkansas Supreme Court said the act trod upon prerogatives of the courts and limited people’s ability to be compensated for harm, which the Arkansas Constitution guaranteed.

But the most divisive issue of the early twenty-first century was homosexuality. In 2002, in the case of Larry Jegley v. Elena Picado, et al., the Supreme Court voted 5–2, with Hannah in the majority, to strike down the state’s sodomy statute, which made it a crime to engage in homosexual acts. The case would be cited many times, in Arkansas and elsewhere, for the premise that homosexual relationships could not be criminalized. The Arkansas court said the sodomy statute violated the Arkansas Constitution’s implied right to individual privacy. A year later, the U.S. Supreme Court cited the Arkansas decision when it reversed (Lawrence v. Texas) its own precedent from 1986 and invalidated state laws criminalizing homosexual relationships. Subsequently, in 2011, the state Supreme Court struck down an initiated act, approved overwhelmingly by the voters in 2008, that barred homosexual couples from adopting children or serving as foster parents.

Also controversial was the case of the West Memphis Three, which Hannah’s court reopened in 2010. The court ordered the trial court to examine DNA evidence that seemed likely to vindicate the men—who came to be known as the West Memphis Three—who had been convicted sixteen years earlier as teenagers for the murder of three boys at West Memphis (Crittenden County). The state negotiated a settlement with the three men that allowed them to go free; the murders are still unsolved.

Despite the controversial and often unpopular rulings, Hannah was reelected in 2012 without opposition, but the elections of 2010 and 2012 also brought three new justices to the court, and they—together with a justice serving a temporary appointment by Governor Beebe—formed a phalanx against Hannah and the other two veteran justices, sometimes overruling the chief justice’s administrative acts.

The internal discord surfaced publicly in 2014 on the issue of same-sex marriage. Arkansas had adopted, also overwhelmingly, a constitutional amendment in 2004 that prohibited marriages and civil unions of same-sex couples or recognition of unions that occurred in other states. In anticipation of an almost certain ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court that such marriages could not be prohibited, suits were filed in Arkansas and many other states to strike down state laws barring them. A federal district judge and a state judge in Pulaski County ruled in 2014 that the Arkansas law violated the U.S. Constitution. The state judge ruled that it also violated basic rights provided by the Arkansas Constitution. Arkansas legislators threatened to impeach the state judge.

After the case was argued before the state Supreme Court, the justices voted in conference, a secret proceeding, to invalidate the 2004 law, but the decision was never released. It became evident that most of the justices wanted to avoid handing down any decision. Hannah and two other justices, however, insisted that the court make its ruling, no matter the political consequences. The decision was stalled until one of the three, Justice Donald L. Corbin, left the bench on January 1, 2015, because of mandatory retirement. Then the controlling quorum of justices ordered the deliberations to begin anew with a new justice. Justice Hannah, however, believed it was the court’s solemn obligation to render a decision one way or the other.

The court fell silent on the case until the U.S. Supreme Court, on June 26, 2015, in Obergefell v. Hodges, ruled that marriage was a right that states could not deny to same-sex couples. The Arkansas court then issued a per-curiam order saying the Arkansas case was moot.

Suffering from cancer, Hannah retired at the beginning of the court’s fall term in September 2015. He died on January 14, 2016. Later that day, another member of the court revealed that a majority of the court had steadfastly refused to adopt a per-curiam order recognizing Hannah’s service on the court, a recognition it had routinely given to every justice, appointed or elected, who left the court. Protests followed from a former attorney general and others. The next day, the court hastily issued a per-curiam order, and the three justices who had been his chief antagonists issued short personal statements recognizing Hannah’s service.

He is buried in Velvet Ridge Cemetery in Velvet Ridge (White County).

For additional information:

Brummett, John. “More Court Pettiness.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 17, 2016, p. 5H.

Obituary of James Robert Hannah. Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 17, 2016, p. 5B.

Willems, Spencer. “Hannah, for Decade Chief Justice, Dies.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 15, 2016, pp. 1B, 6B.

———. “Justices’ Decree Honors Hannah.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 16, 2016, pp. 1B, 7B.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Law

Law Wright v. Arkansas

Wright v. Arkansas James R. Hannah

James R. Hannah

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.