calsfoundation@cals.org

Race Riots

A race riot is any prolonged form of mob-related civil disorder in which race plays a key role. The term is most often associated with mob violence by or against a minority group. The motivations for such violence can vary significantly, and once properly defined, the difference between collective violence and riot is somewhat arbitrary. For instance, many lynchings targeting African Americans are considered race riots, as they involved large numbers of whites and were the fatal culmination of existing racial tensions. The 1927 lynching of John Carter in Little Rock (Pulaski County), with the slaying of a white girl as a catalyst, involved a prolonged assault against the city’s black community and is often considered a riot. However, other lynchings and episodes of local racial violence have involved smaller numbers of people, been more low key, or had a shorter duration, and thus failed to meet common understandings of what defines a riot.

Types of Race Riots

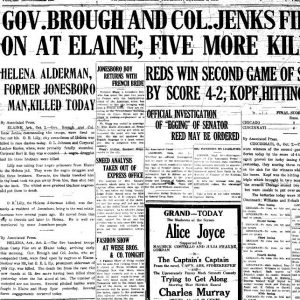

Race riots in Arkansas usually coincided with a handful of regional and national factors: economic difficulty, political participation and strife, and/or increased local racial tensions. For example, Arkansas’s most infamous race riot, the Elaine Massacre (1919), has been explained as part of the first Red Scare, a result of economic difficulties for black sharecroppers, and a culmination of deep-rooted white supremacy amongst the region’s whites flaring violently in response to the rising economic and social expectations of African Americans generated during World War I. Often, racially motivated violence served as a cause for riot. The Argenta Race Riot in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) was ignited when racial animosities flared after the slaying of two black men in September 1906. A wave of race riots occurred in the state in the aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968. With such a wide variety of motives varying over time and place, it is difficult to generalize about race riots, and some events dubbed “riots,” such as the Brushy Island Riots of the late 1910s, exhibit characteristics more common to feuds.

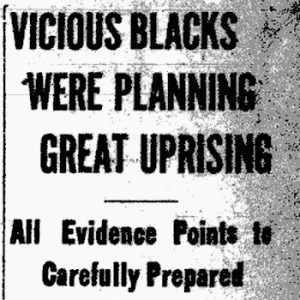

Nevertheless, three patterns of race riots emerged in Arkansas. In areas with large concentrations of African Americans, race riots were extremely violent, disciplinary affairs by which whites sought to preserve the traditional social order. Such was the case in Pulaski County, where African Americans made up more than thirty percent of the population, during the John Carter lynching. During the St. Charles Lynching of 1904, white mobs assaulted the majority black population, which they believed was planning organized racial violence. These types of riots remained a fixture of Arkansas race rioting well into the twentieth century, when whites rioted outside of Central High School in Little Rock in 1957 to protest the school’s forced desegregation.

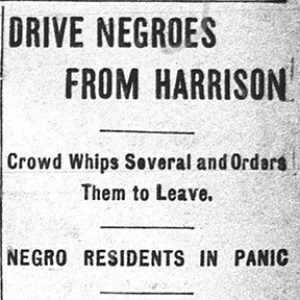

In whiter counties, such as those in northern and western Arkansas, African Americans were not as integral to local economies and were prone to being forcefully expelled by white mobs and white supremacist organizations. This was most famously the case in Harrison (Boone County)—where the non-white population rarely exceeded one percent—in 1905 and again in 1909, when white mobs forcefully exiled nearly every non-white person in the county. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a wave of racial expulsions swept across northern and western Arkansas, creating what are known as “sundown towns.” Incidents of racial expulsions in Arkansas have been recorded from Reconstruction until the mid-twentieth century.

In the twentieth century, when black Arkansans began organizing against white violence, a new type of race riot emerged: the black riot. Marked by a backlash against white racism or acts of violence, these types of riots tended to occur in areas with sizable, organized black communities, such as Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). Many of these riots originated as protests during the civil rights movement—as was the case in Little Rock in 1968. As African Americans began to form an increasingly powerful solidarity in support of desegregation and their own civil rights, this form of riot became more common. However, as the fervor of the civil rights movement died down, all forms of rioting came to an end in Arkansas.

History of Race Riots

Since there were no slave rebellions in Arkansas, and military massacres are usually analyzed separately from race riots, the first incidents of racially charged mob violence in the state occurred shortly after emancipation. As the society in which they were born lay in shambles, white Arkansans resisted change viciously. Throughout Arkansas’s Reconstruction period, lynch mobs, white supremacist organizations, and white riots were relatively common. Freedmen’s Bureau agents often reported incidents of African Americans and white Republicans being mistreated by gangs of whites such as the Cullen Baker gang, which terrorized and murdered dozens of African Americans across Arkansas and Texas in the late 1860s. Black political participation was met with fierce opposition by white mobs and the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). The situation grew so hostile that Governor Powell Clayton was forced to declare martial law in fourteen counties in which civil authority had failed to prevent violence—violence, in this case, directed toward blacks, as well as toward white federal officials and Republicans. Black Arkansans fought back through the creation of their own militia, which on occasion engaged in its own atrocities as it battled with the KKK. Given the sheer scale of violence in Reconstruction Arkansas, it is impossible to make a clear demarcation between race riot and guerrilla violence—nor are easy divisions between racial and political violence immediately discernable, as exemplified by such incidents as the Chicot County Race War of 1871 and the Black Hawk War of 1872. Where later generations may have seen race riots flare from relative peace, racial violence and civil disobedience in Reconstruction Arkansas were the norm.

The period after Reconstruction brought an economic downturn for both white and black tenant farmers and a growth of black communities, as African Americans migrated to areas with established African-American populations. This tight-knit community life allowed many black Arkansans to accumulate wealth, creating the first black middle class in the state’s history, however small. The Texarkana Race Riot of 1880 was sparked by a land dispute. The Howard County Race Riot of 1883 also occurred in the midst of this era, sparked by the murder of a white man by a black man. After a large white riot, a wave of arrests, and a host of speedy trials, four black men were murdered and another was executed. However, since most of those African Americans involved were relatively prosperous landowners, the death toll was much lower than it could have been. Indeed, local white lawyers willingly came to the defense of some of the forty-three men on trial for the murder of a single white man, convincing Governor James Henderson Berry to commute the remaining death sentences. The backlash by increasingly impoverished rural whites, however, only grew in the late 1880s.

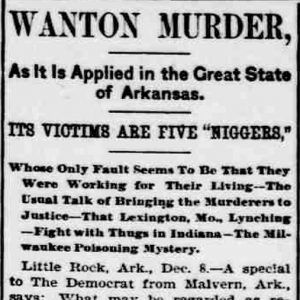

Most mob activity in the Gilded Age was a response to black political participation and economic success. Political violence sparked riots in Conway County throughout the 1880s, as white supremacists forcefully (often violently) kept black citizens—a large percentage of the county’s population—from voting. As racial tensions increased, so did race riots. During this era, Arkansans saw a surge of lynchings, beatings, and racial expulsions. One incident in Crittenden County in 1888 involved the forceful removal of around twenty African Americans at gunpoint by white mobs. In Forrest City (St. Francis County) in 1889, local political tensions led to many days of racial tensions and mob activity, which resulted in the death of Americus Neely, a prominent black leader, as well as several white Republicans. In Lee County in September 1891, fifteen African Americans, who were believed to be organizing a strike, were rounded up, and nine were hanged by a white mob. In the aftermath of this widespread violence and intimidation emerged a new era in the history of African Americans in Arkansas and the South: Jim Crow and disfranchisement, the latter achieved primarily through the Election Law of 1891 and a later poll tax. However, these increasingly restrictive methods for the social control of the black population did not diminish white attacks upon African Americans. In 1892 in Texarkana (Miller County), a white mob of approximately 1,000 people lynched Ed Coy, and later that year a month-long series of racially motivated attacks rocked Calhoun County. Later events of the decade include the Atkins Race War of 1897, the Lonoke County Race War of 1897–1898, and the Little River County Race War of 1899.

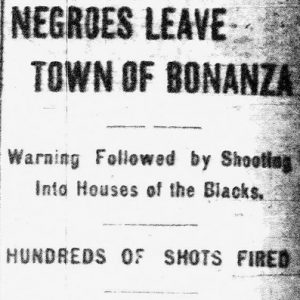

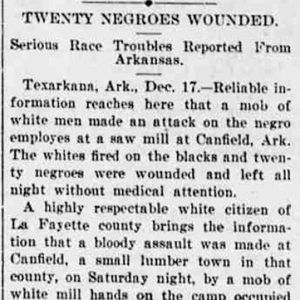

Several incidents in the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries had, at least in part, economic motives, as whites working in industrial jobs sought to drive away African Americans they saw as competition for employment, as seems to have been the case with the Marked Tree Race Riot of 1894. The year 1896 encompassed such events as the Canfield Race War and the Polk County Race War, as well as a variety of racial conflicts in southern Arkansas, sparked by white attempts to force black laborers away from job sites in the timber and railroad industries. The following year, whites again attacked black mill workers during what has been called the Nevada County Race War. In western Arkansas, the Bonanza County Race War of 1904 typified the kind of racial violence that occurred in coal mining districts across the nation, while white vigilantes attacked African Americans working in a variety of industries during the Walnut Ridge Race War of 1912. Such violence, especially when carried out by masked men, often under the cover of darkness, was called “nightriding” or “whitecapping.”

Even though the early twentieth century saw little political participation or economic advancement for Arkansas’s black citizens, race riots persisted. In St. Charles (Arkansas County) in 1904, white mobs killed thirteen African Americans whom they believed were planning a race war. In several towns—such as Cotter (Baxter County), Paragould (Greene County), and Harrison—black families were forced to leave or face brutal retaliation. (The violence in Paragould consisted of several incidents over a period of twenty years, while the Cotter event occurred on a single day, though animosity against African Americans had been building for years.) A gun battle between a black man and three white men in El Dorado (Union County) in 1910 sparked a wave of mob attacks on black homes and businesses. During World War I, rumors of German spies encouraging black revolt brought an outburst of white paranoia, mob arrests, and lynchings in Hampton (Calhoun County). Nevertheless, the experiences of war motivated African Americans to fight against their deplorable situation back home, and those who remained in Arkansas became discontented with their subjugation.

As author and historian Grif Stockley wrote, “The summer of 1919 was a disaster for race relations all over the country.” African Americans all over the South were pushing the boundaries of the established racial status quo, to which white supremacists responded with mob violence and murder. Racial tensions in Phillips County culminated in the Elaine Massacre, which left hundreds of blacks and five whites dead. The assault and murder of a white woman in rural Crawford County in late 1923 resulted in the expulsion of an entire black community by white mobs. In 1927, a white mob tracked down John Carter, a black man accused of assaulting a white family, and lynched him. The crowd proceeded to drag his body through the streets of Little Rock, setting it ablaze as a warning to the city’s black population. However, the heyday of lynching had long passed, and John Carter was one of the final victims of Arkansas lynch mobs.

The Great Depression and World War II saw a decrease in white mob violence. African Americans began migrating to Arkansas’s cities and towns, eliminating rural isolation which increased the severity of white riots in the previous decades. At the same time, the poor economic conditions of the Great Depression crossed color boundaries, forcing many instances of racial cooperation. After the creation of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union in 1934, white mobs intimidated, harassed, and beat members of the interracial organization, forcing many of its members to flee. However, none of the violence was extensive enough to be considered a riot by historians. Indeed, the ability of an interracial union to achieve relative success was key in instilling confidence in the state’s black communities, reducing the severity of future white riots. World War II only saw the acceleration of Arkansas’s urbanization and black organization. Isolated incidents of violence by whites were met with stiff organized responses from African Americans in the form of protest and condemnation. Arkansas race relations underwent a fundamental change in the period before the civil rights movement: no longer was white supremacy taken for granted.

As race relations in the South were transformed, so were those in Arkansas. The nonviolent strategy of the civil rights movement brought a new televised drama to race riots and protests across the country. During the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, racial tensions culminated in white mob activity outside of Central High School, forcing the evacuation of the black students recently admitted. However, no one was seriously injured, and the mob was contained. While civil rights activists in many counties met stiff resistance and even threats of physical violence, tensions did not flare to the dramatic levels they reached in other states until after the death of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968. Shortly after King’s assassination, Pine Bluff and Hot Springs (Garland County) saw destructive rioting. In August, a peaceful protest in Little Rock turned violent, requiring National Guardsmen to calm the crowds. The next year saw widespread mob activity by both blacks and whites in Forrest City over civil rights. National Guardsmen were once again required to calm the increasingly hostile mobs. The following years saw similar events unfold in Arkadelphia (Clark County), Earle (Crittenden County), El Dorado, and Marianna (Lee County), as well as smaller incidents throughout the state; in Earle, for example, white mobs attacked African Americans protesting the segregation of schools, still ongoing in 1970. However, by the end of 1972, racially charged mob activity in the state dropped off dramatically.

While the situation for black Arkansans in the modern era has differed little from that of black populations across the United States and the South, rioting has not been part of Arkansas’s recent history as it has been in more-populous metropolitan areas. This could be due in part to the relatively small population of Little Rock compared to other cities where riots have occurred since the late 1970s. Similarly, modern society largely shuns violent forms of civil disobedience as a means of protest. As a result, since the 1970s, few race riots have occurred in the United States, and none of those have occurred in Arkansas. Nevertheless, as long as there is a visible discrepancy in life opportunities between the state’s racially defined groups, the potential exists for an isolated incident to escalate into a violent race riot.

For additional information:

Anthony, Michael. “Otherwise, You Will Have to Suffer the Consequences: The Racial Cleansing of Catcher, Arkansas.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2023. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/4834/ (accessed October 23, 2023).

Barnes, Kenneth C. Who Killed John Clayton? Political Violence and the Emergence of the New South, 1861–1893. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998.

Burke, Jordan C. “White Discipline Black Rebellion: A History of American Race Riots from Emancipation to the War on Drugs.” PhD diss., University of New Hampshire, 2020. Online at https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2544/ (accessed May 19, 2023).

Graves, John William. Town and Country: Race Relations in an Urban-Rural Context, Arkansas, 1865–1905. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Kirk, John A. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Lancaster, Guy. “Brush Fires: A Chronicle of Murder, Arson, and General Mayhem on Brushy Island in Northern Pulaski County.” Pulaski County Historical Review 71 (Spring 2023): 26–41.

———. Racial Cleansing in Arkansas, 1883–1924: Politics, Land, Labor, and Criminality. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014.

Lancaster, Guy, ed. Bullets and Fire: Lynching and Authority in Arkansas, 1840–1950. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018.

———. The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819–1919. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

———. “Nightriding in Arkansas.” Special issue, Arkansas Historical Quarterly 81 (Autumn 2022).

Lloyd, Peggy S. “The Howard County Race Riot of 1883.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Winter 2000): 353–387.

McCool, B. Boren. Union, Reaction, and Riot: A Biography of a Rural Race Riot. Memphis: Memphis State University, 1970.

Mitchell, J. Paul, ed. Race Riots in Black and White. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1970.

Stockley, Grif. Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

Stockley, Grif, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919. Rev. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Waskow, Arthur I. From Race Riot to Sit-In, 1919 and the 1960s: A Study in the Connections between Conflicts and Violence. New York, Doubleday & Company, 1966.

Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth. American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Ryan Poe

Fayetteville, Arkansas

My family was one of two or three white families living in Little Rock, Arkansas, near East 6th St. in 1968 that were burned out or forced out with gun fire, and unknown people on our property. Many businesses were burned to the ground. I watched through a window fan as my father fired shots into the air at unknown black people on our property. We found a one-gallon milk jug full of gas the next day at the edge of our property. Shortly after, I watched the National Guard as they crept, guns drawn, through our back yard like they were in Vietnam. I was 11 years old. What an impression I gained about blacks because of that. Before that, I had run in the streets with other black neighborhood children. Today it’s a forced mistrust of blacks that I feel, not of fellow playmates that I grew up with. And I still would like to see what my ex-playmates grew up to be, what kind of people they are now. I’m 60 now, and wiser. Some things are not meant to be, I guess?