calsfoundation@cals.org

Brushy Island Riots of 1915–1917

The area known as Brushy Island lies within the municipal boundaries of Sherwood (Pulaski County) and was the site of what newspapers described as a series of “race riots” starting in 1915. The violence, primarily represented as being between groups of white and Black farmers in the area, in many respects constituted more an ongoing feud than any sort of riot, however.

A January 4, 1917, report in the Arkansas Gazette on the “riots” described Brushy Island as consisting of “several hundred acres almost completely surrounded by bayous. The land was at one time covered with a dense forest, which has been cut away, leaving the Island dotted with stumps.” Newspaper reports of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries portray the area as a hotspot for criminal activity, most particularly cattle thievery, moonshining, and arson.

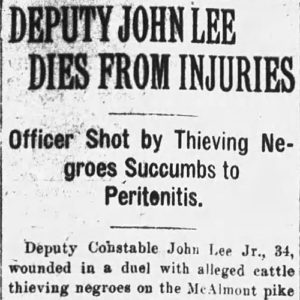

On November 25, 1915, the Arkansas Gazette reported that Deputy Constable John Lee Jr., age thirty-four, had died after being “wounded in a duel with alleged cattle thieving negroes on the McAlmont Pike” two days prior. The suspected cattle thieves were Leonard Moore, Robert Coleman, and Leonard’s brother Josh Moore. A November 28, 1915, report gives the sequence of events as follows: Lee, apparently becoming aware at night that one of his cows had been stolen, pursued and overtook the three suspected thieves and “was peering beneath a cover” in their wagon when Leonard Moore fired upon him, hitting Lee in the abdomen and throwing him from his horse; Moore fired again, hitting Lee in the thigh, but Lee was able to fire his pistol from the road, hitting Moore in the shoulder. Lee lived long enough to convey some information about his apparent attackers.

Immediately following the spread of news about Lee’s death, several “negro shacks” were burned in the Brushy Island neighborhood. According to the Gazette, the first home burned was that of Robert Coleman, whose wife reported that “her husband’s house, barn and cribs were burned and 300 bushels of corn and a quantity of cotton were destroyed Wednesday night.” Next, the home of Leonard Moore was “riddled” with shot and set on fire. The attackers next set “a negro schoolhouse and a negro church” on fire. This was Clayton Baptist Church.

In response to the fires, Deputy Sheriffs George Rison, James Drake, Charles Roberts, and Linsey Roberts proceeded to Brushy Island and there arrested a number of relatives of Lee, as well as an employee of John Lee Sr. and others. The home of witness Annie McPease was burned on November 29, no doubt in response to her having provided information on the apparent perpetrators to law enforcement; hers was the third Brushy Island house to be attacked by arsonists. In addition, unknown parties shot into a shed “adjoining the house of Sidney Hines, negro, who owned the house where lived Leonard Moore.” On December 3, 1915, three more white men were arrested on rioting and arson charges, bringing the total at this point to eight: Louis (or Lewis) Lee (“cousin of the slain deputy constable”), William (Will) Lantrip (“brother-in-law of John Lee”), Thomas (Tom) Poe, Albert (Al) Keel, Frank Keel, Henry Lee, Peter (Pete) Lee, and Richard (Dick) Forbes.

On December 13, Judge W. E. Woodruff dismissed charges against all eight white men at the request of Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Harry Hale. However, a grand jury inquiry soon began, spurred in large part by “reports that officers interested in handling the Brushy Island cases several weeks ago have been threatened with bodily harm.” The grand jury did indict John Lee Sr., Henry Lee, Louis Lee, Peter Lee, Richard Forbes, William Lantrip, and Thomas Poe.

The trials of both Leonard Moore, on a charge of murder and grand larceny, and the other men, on charges of arson, were set to begin the week of March 27, 1916. At his trial, Moore claimed self-defense, stating that Lee had “cursed him” after Moore denied the accusation of theft and “exclaimed with an oath that he was a liar and that he intended to kill him.” However, Moore was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter on March 29, 1916, in the First Division Circuit Court and sentenced to five years in the state penitentiary. Charges against Josh Moore and Robert Coleman were later dismissed.

While the white defendants awaited trial, a barn belonging to Richard Lee, brother of the late John Lee Jr., burned on April 2, 1916. He reportedly lost “a large quantity of corn, hay and fodder” and was “firmly convinced the barn was set on fire,” although the authorities were not able to confirm this. Meanwhile, local Black residents filed a civil suit against John Lee Sr., seeking $2,000 specifically for the destruction of Clayton Baptist Church. The plaintiffs were represented by the Bratton and Bratton law firm, headed by Ulysses S. Bratton, who would later achieve greater renown following the Elaine Massacre of 1919. The records of this suit at the Pulaski County Courthouse do not record anything aside from the original suit, the summons delivered to John Lee Sr., and his answer, and so apparently the suit was unsuccessful.

In late October 1916, Robert Coleman returned to Brushy Island “to live with neighbors until he could rebuild his ruined home.” Later that year, he and some of his neighbors built a small log cabin for him and his family. On January 1, 1917, they had completed plastering between the logs and “went to a neighbor’s house to eat supper.” As they were getting ready to return, the Moore home was dynamited by unknown attackers. Pinned to a post near the wrecked cabin was a “typewritten note” that read: “You are the boldest nerve negro we ever saw to go back and buttle down under the nose of those little children who you caused their father to be killed. Never so long as one of his friends live, you will never do so.”

The troubles continued. By early March 1917, the Gazette was reporting that Brushy Island whites, specifically John Trummel and Dick Trummel, had “warned Burton Baker, negro farmer on the island, that no negroes should use a road leading to the island or cross the only bridge across the lake surrounding the island.” Baker found this particularly grating, given that “the road to his farm is partly on his land and that the bridge across the lake is on his land,” adding that “when the bridge was constructed he furnished all the piling.”

Later that month, John Lee Sr. went on trial, his case being heard first after the judge agreed to separate the cases and not try the men as a group. Lee asserted his innocence, saying that “he had always been a friend to the negroes on Brushy Island and that he had never had any trouble with them,” and adding that he had helped organize and build the school in the area. Instead, he placed the blame upon “two factions” among the Black population who “had been quarreling and fighting ever since the school was built.”

On March 29, Lee was acquitted on the charge of arson. On May 14, 1917, the indictments against the remaining white defendants were “nolle prossed,” which is to say that the prosecutor had filed noticed that he was abandoning the prosecution. Leonard Moore was paroled on April 10, 1919, after serving three years of his original five-year sentence.

For additional information:

Lancaster, Guy. “Brush Fires: A Chronicle of Murder, Arson, and General Mayhem on Brushy Island in Northern Pulaski County.” Pulaski County Historical Review 71 (Spring 2023): 26–41.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Law

Law Brushy Island Riots Story

Brushy Island Riots Story

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.