calsfoundation@cals.org

Helena-West Helena (Phillips County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34º31’46″N 090º35’30″W |

| Elevation: | 188 feet |

| Area: | 13.09 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 9,519 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | November 16, 1833/May 23, 1917 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

614 |

1,551 |

2,249 |

3,652 |

5,189 |

5,552 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

8,772 |

9,112 |

8,316 |

8,546 |

11,236 |

11,500 |

10,415 |

9,598 |

7,491 |

6,323 |

|

2010 |

2020 | ||||||||

|

12,282 |

9,519 |

Helena-West Helena is located on the Mississippi River about seven and a half miles below the mouth of the St. Francis River. Helena was incorporated in 1833 and prospered as a river port, while West Helena began as a railroad town, incorporated in 1917. The two cities united their school systems in 1946 and merged into one city (preserving both names) on January 1, 2006.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Two land speculators, Sylvanus Phillips and William Russell, created the present town site of Helena, which was originally part of a Spanish land grant. Phillips, who played the major role in the establishment of the town, arrived in the area about 1797 and moved to the present site of Helena around 1815. On May 1, 1820, the territorial legislature carved out part of Arkansas County and created a new county named in honor of Sylvanus Phillips. The legislature also gave permission to create a town, and the 640-acre site that was to become Helena was platted in December of the same year. In 1833, some two years after Phillips’s death, the town of Helena was incorporated and named after his daughter, Helena Phillips, who had died on August 28, 1831, at the age of fifteen.

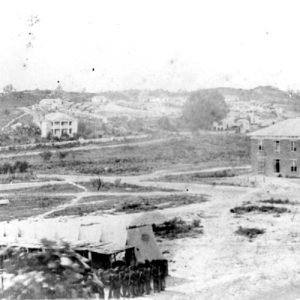

The new town rested on the southern edge of Crowley’s Ridge and was bordered on the east by the Mississippi River. Unfortunately, much of the original site was in the river’s floodplain and, therefore, suffered periodic inundations until substantial levee systems were constructed in the late nineteenth century. West of Helena, the ground was relatively flat and out of the floodplain, but to the south, the land was a vast lowland of cypress swamps and oxbow lakes.

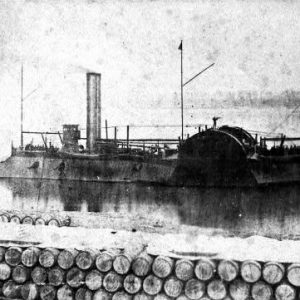

The lands surrounding Helena were well suited for the production of cotton, but the periodic flooding and poor drainage initially limited large-scale operations to the high ground west of the city. Agriculture slowly expanded southward, but only as farmers built small levees and drained the land. Meanwhile, the vast stands of lowland trees such as cypress and tupelo and the hardwoods along Crowley’s Ridge were soon being exploited. In 1826, a sawmill began operations in Helena, and the timber industry continued to grow until well into the twentieth century. Cotton and timber eventually dominated the local economy, but much of Helena’s early growth was associated with the steamboat age. The town, which was conveniently located between Memphis, Tennessee, and Vicksburg, Mississippi, became a stopover for the steamboats that revolutionized river transportation. There, captains took on supplies and restocked their fuel bunkers from the vast quantity of cottonwood trees harvested by local wood cutters. They also loaded cotton and timber and discharged finished goods for the growing community.

Helena, like many river towns, became known as a place that attracted thieves, gamblers, and other outlaws who inhabited frontier America. In 1835, citizens in Helena responded to the growing lawlessness by forming an anti-gambling society to rid the town of some of its worst elements. By the mid-1850s, much of the rough edges of the river town had disappeared. By then, Helena had three newspapers, six private schools, at least a dozen churches, a temperance society, several subscription libraries, and an occasional public lecture.

Between 1850 and 1860, improved land in the area increased by 219 percent, and cotton production grew by 442 percent. Plantation agriculture now dominated the economy with the number of slaves rising by 245 percent in the same period. In Phillips County as a whole, the 1860 census recorded 8,941 slaves in a total population of 14,877.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

By the beginning of the Civil War, Helena was the largest Arkansas town on the Mississippi River, and slavery was entrenched in the social and economic life of the area. During the war, hundreds of men from the surrounding area joined the Confederate army, and the region eventually produced seven Confederate generals. However, the support for the Confederacy among whites was never unanimous. After the Emancipation Proclamation, hundreds of freedmen joined the Union army.

The Helena Artillery Battery was a Confederate unit organized in Helena in 1861. Also known as Key’s Battery in honor of one of its commanders, the unit served for the duration of the Civil War.

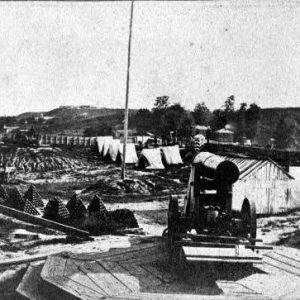

On July 12, 1862, elements of Brigadier General Samuel Ryan Curtis’s Union army arrived in Helena, and the town of about 1,500 people remained under Federal control until the end of the war. Helena became an important post for the Union army, serving as a depot to support operations against Vicksburg, Mississippi, and as a base to attack Rebel resources in the Delta. A small skirmish at Helena took place in September 1862, as did smaller military encounters in and around Helena in October 1862, December 1862, and January 1863.

Batteries A, B, C, and D were fortifications used by the Federal army to protect Helena from enemy attack. Along with Fort Curtis, these fortifications formed the core of the Helena defenses, most notably during the Battle of Helena. On July 4, 1863, Confederate forces, in a desperate attempt to divert Union forces from the siege of Vicksburg, attacked the Union garrison. They were repulsed with heavy losses.

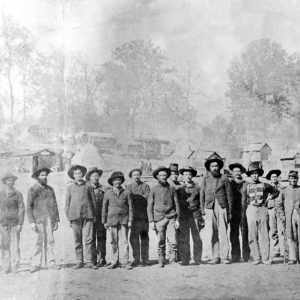

Guerrilla fighting and occasional forays by Confederate cavalry continued to plague the region, and, by the end of the war, thousands of freedmen and displaced whites had moved into Helena. Most were destitute, but the presence of the Union army did provide some measure of protection for the people, and the town itself escaped the massive physical destruction that many other Arkansas towns saw. Military farm colonies were abandoned farms and confiscated plantations leased to Unionists who, in turn, hired freedmen to work the land; this provided newly freed slaves with a way to survive while not using supplies intended for the army. The response was fighting such as that in Skirmish at Lamb’s Plantation, which pitted Southern cavalry against freed slaves and Northern civilians.

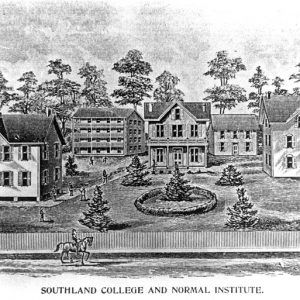

In 1864, two Indiana Quaker missionaries established near Helena an orphanage and school which would become Southland College, the first institution of higher education for African Americans west of the Mississippi River. The school survived through several decades before closing in 1925.

In 1868, an African-American man named Lee Morrison was lynched near Helena in retaliation for a number of murders he was presumed to have committed.

The Helena Confederate Cemetery was created in 1869 to house the bodies of seventy-three known and twenty-nine unnamed Confederate soldiers, most of whom died at the Battle of Helena. The cemetery was much later added to the National Register of Historic Places.

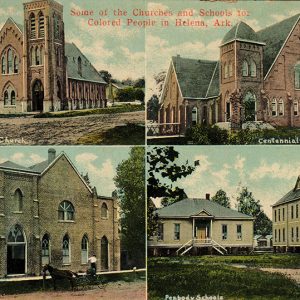

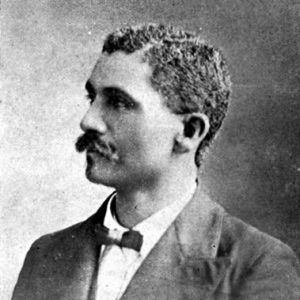

With black enfranchisement during early Reconstruction, the citizens of Helena elected a number of African Americans to public offices, but that trend began to decline in the late 1870s when Southern whites returned to political power. Among the leaders of Helena in the last years of the nineteenth century were Joseph Cantrill Barlow, a Civil War veteran who began as a store clerk, acquired a hardware business, and was elected mayor of Helena in 1878; John Sidney Horner, a law clerk, judge, and merchant who lost a fortune during the Civil War but rebuilt his business after the war and was the first president of the Bank of Helena; and William M. Neil, the editor and owner of the Helena World. Elias Camp Morris served as pastor of Centennial Baptist Church, an African-American congregation in Helena. He became the leader of several African-American Baptist organizations, including the National Baptist Convention. Morris was also active in the Republican Party in Arkansas.

By the turn of the century, sharecropping and codified segregation defined the relationship between the races. At the same time, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were eras of real economic growth as levee projects continued to open more timber and farm lands, while railroads provided the means to cheaply move the resulting raw materials to distant markets. During this period, Helena continued to develop as a regional economic center, and the need for additional industrial sites, especially for lumber mills, continued to grow.

Early Twentieth Century

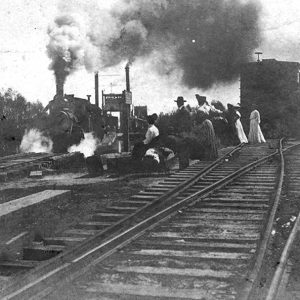

Eventually, several business leaders began developing property west of Helena and then connected it to the old town by a new trolley system. The need for a new community was made clear at the completion of the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad in 1907. City leaders acquired 2,300 acres three miles northwest of Helena, land that had been the Clopton Plantation. The land survey was completed on March 28, 1910; from its beginning, West Helena was deliberately segregated, with separate housing areas for white and black residents. On May 23, 1917, the new city was officially incorporated as West Helena. Early lumber and hardwood plants in the new city included the Helena Veneer Company, the Org Chair Company, Upton & Alger, the Southwestern Wagon Company, and the Dennison Sawmill. Within a short time, the new city could boast of an amusement park, a theater, a band stand, and a small zoo. It was also home to the posh Helena Country Club.

The hardwood lumber industry provided many jobs in Helena and West Helena during the early part of the twentieth century, but several events caused the industry to decline. Five companies that manufactured barrel staves lost their primary customers when the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, prohibiting the manufacture, sale, or transportation of alcoholic beverages, went into effect in 1920. Automobiles replaced wooden wagons (although early models were made with many wooden parts that were manufactured in Helena and West Helena), and metal buckets replaced wooden buckets. Finally, the floods of 1927 and 1937 severely damaged the infrastructure of Helena and West Helena, causing them to forfeit their place in the nation’s lumber market. The Depression also severely damaged the industrial and agricultural vitality of the region. When Will Rogers toured the state of Arkansas in 1931, he included Helena on his itinerary, raising $1,500 from his appearance to support various unemployment committees.

The Supreme Royal Circle of Friends of the World, also known as the Royal Circle of Friends (RCF), was an African-American fraternal organization founded in 1909 in Helena by Dr. Richard A. Williams. Membership dues covered physicals, life insurance, and sick pay, as well as distinctive headstones. The organization ran its own newspaper and social events, and later provided free care to members at RCF-owned hospitals. The Helena-based organization eventually spread to nine states and boasted a membership of over 100,000. It successfully provided services to its members until the death of its founder in 1944, after which it soon folded.

In 1920, an African American professor named J. W. Gibson was murdered by a night watchman for carrying an unloaded gun. Whether this event should be considered a lynching or not is disputed. In 1921, an African American young man named William Turner was lynched for allegedly attacking a young white girl. According to newspaper accounts, it was the first lynching in Helena.

World War II through the Faubus Era

World War II returned some stability to Helena and West Helena for a time, as the nation’s industry kept up with war’s demands. The population of the two cities, which had been shrinking, began to grow. A Prisoner-of-War Work Camp was built on the Phillips County fairgrounds in West Helena, opening on September 10, 1942. It first housed Italian prisoners of war and, later, German prisoners of war.

Around 1940, the United States wanted to increase the strength of the Army Air Force (AAF). To do this, the number of pilots had to be increased, and this resulted in several levels of flight training schools opening all over Arkansas. Primary contract flying schools were established in Helena, Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), and Camden (Ouachita County); basic flying schools were established in Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County) and Newport (Jackson County); and advanced flying schools were established in Stuttgart (Arkansas County) and Blytheville (Mississippi County). Only those who graduated from all levels became AAF pilots. After the end of World War II, the Thompson-Robbins Air Field in Helena returned to civilian control and today operates as Thompson-Robbins Airport.

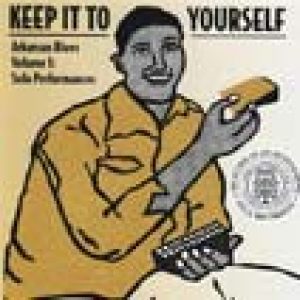

On November 21, 1941, KFFA in Helena began broadcasting a program called King Biscuit Time. Featuring local performers of a style of music called the blues, which had developed among African Americans in the Southern states, this radio program helped to revolutionize music in the United States, which went on to have a worldwide impact. King Biscuit Time helped to establish the careers of many artists who went on to record in Chicago, Illinois; Memphis; and other music centers. Helena natives Robert Lockwood Jr., Robert Lee McCollum, Roosevelt Sykes, and Sonny Boy Williamson are among those whose legendary careers were made possible by the King Biscuit Time radio program.

The twin cities continued to grow steadily until the 1960s, when the mechanization of farming operations, the decline of the timber industry, and union trouble in several plants eventually cost the two communities thousands of jobs. These economic problems were compounded by continued racial turmoil and high levels of poverty. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) began working to integrate public places in Helena, including Henry’s Drug Store and Habib’s Cafeteria, in November 1963. Thirty demonstrators were arrested, and their leaders were charged with “inciting to riot.” The Civil Rights Act of 1964 endorsed the validity of their efforts to integrate Helena businesses, but continuing attempts to challenge old rules met with varying degrees of success. The SNCC also encouraged black parents to exercise their rights to send their children to historically white schools. Helena and West Helena had responded to court-ordered desegregation by creating a “freedom of choice” plan. Community pressure undermined the existence of “choice,” preserving the white-only and black-only schools in spite of the new laws on the books. Several years passed before true school desegregation occurred in Helena and West Helena.

Modern Era

Phillips County Community College—now Phillips Community College of the University of Arkansas—opened in Helena in 1966. Beginning with 250 students, the college has grown to an enrollment of more than 2,400, with a variety of programs to serve the people of eastern Arkansas. The Arkansas Blues and Heritage Festival began in Helena as a one-day celebration in 1986 and grew to become an annual three-day event drawing more than 100,000 people. The Delta Cultural Center opened in Helena in 1990. In addition to serving as a visitors’ center, the Delta Cultural Center preserves several historic properties, including a Missouri Pacific Railroad Depot, the Cherry Street Pavilion (an outdoor concert stage), and the Temple Beth El, Helena-West Helena’s synagogue.

By the 1970s, the chronic economic distress forced a few leaders to suggest that the two cities might better address their common problems by governmental consolidation. Opponents to the merger, who feared losing influence, quickly killed the proposal. However, the proponents of the merger gained ground as the two communities continued to decline. Finally, after several false starts and lawsuits, the citizens of Helena and West Helena in 2005 voted to consolidate. On January 1, 2006, the new city of Helena-West Helena replaced its predecessors, and a new era began for the communities.

As is true of most Delta cities, the population of Helena-West Helena is mostly African-American—75 percent by the time of the the 2010 census, when the city recorded 12,282 people. By the following census, that population figure had dropped to 9,519. Although some revitalization of the downtown area has occurred in the twenty-first century, with new businesses like Delta Dirt Distillery attracting state and national attention, the river city remains home to numerous buildings either abandoned or in poor architectural condition, as exemplified by the historic Centennial Baptist Church, which suffered a partial collapse in 2020 during a storm. On July 14, 2022, the Arkansas Board of Education placed the local school district under Level 5 supervision due to a lack of licensed teachers; this marked the third time the district had been placed under state direction.

In late June 2023, the Helena-West Helena water systems failed, leaving residents without access to clean drinking water and leading Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders to deploy the Arkansas National Guard to the community to provide potable water to local residents. (Although the cities of Helena and West Helena had merged in 2006, their water systems remained separate.) The system failure was initially blamed on a computer error, but work to fix the problem uncovered multiple other issues, the consequence of infrastructure nearly 100 years old. City officials estimated that the system needed a complete overhaul and that this would cost at least $1 million and perhaps more than $10 million. Gov. Sanders, meanwhile, authorized in early July 2023 a $100,000 loan to the city. The municipal water system failed again in January 2024 after winter weather exacerbated the situation, with underground lines so rife with leaks that the system could not build enough pressure to deliver water to houses and businesses. By early February, after two weeks, water service had been restored to most residents. On July 25, 2024, the Arkansas State Board of Health approved consent decrees for the two water systems covering the city, giving city officials ninety days to produce a long-term plan; this followed a hearing the previous month in which city officials admitted to having violated several state rules relating to the operation of municipal water systems. However, the city continued to be plagued by problems; two large-scale leaks in late September 2024 resulted in water service being shut off for 4,500 residents on the West Helena side for multiple days.

In May 2024, the city council of Helena-West Helena voted unanimously on a request that the mayor, Christopher Franklin, resign “for conduct unbecoming of the office of mayor.” In June 2025, Franklin was arrested for having failed to file tax returns for four of the previous five years. A review of the city’s finances by the Legislative Joint Auditing Committee found a number of unauthorized withdrawals of funds from the city treasury and raised doubts about Helena’s ability to continue operating. Franklin was removed from office in July, and Joseph Whitfield was appointed to finish out his term.

Attractions

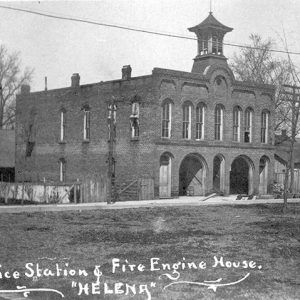

The Helena Museum of Phillips County was built as part of the Helena Library in 1891; a separate building, constructed in 1930, now houses the museum. The two connected structures are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Other structures on the National Register include the Coolidge House, built in 1880; the Phillips County Courthouse, built in 1915; the adjacent Spirit of the American Doughboy Monument erected in 1927; St. Mary’s Catholic Church, completed and dedicated in 1936; and the Helena National Guard Armory, built in 1937. The Cherry Street Historic District is also listed on the National Register.

Notable Figures

In addition to many noted blues performers, Helena-West Helena is also the hometown of country singer Conway Twitty, famed football coach Ken Hatfield, U.S. Senator Blanche Lincoln, and John Stroger Jr., the first African-American president of the powerful Board of Commissioners of Cook County, Illinois. Baseball stars Alex Johnson and Ellis Valentine were from Helena, while Gene Bearden was born in nearby Lexa (Phillips County) and moved to Helena after the end of his professional career; the city’s Gene Bearden Stadium was named after him.

James Camp Tappan was a Confederate general, lawyer, and politician. The James C. Tappan House, built in the Southern Colonial style, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Caroline Shawk Brooks moved to the city from Ohio and there developed her skills as a sculptor of butter, achieving fame across the globe. James Millander Hanks was a U.S. congressman. Jacob Trieber was the first Jew to serve as a federal judge in the United States; some of his rulings, such as those regarding civil rights and wildlife conservation, have had long-lasting implications. The federal courthouse in Helena-West Helena is named after him.

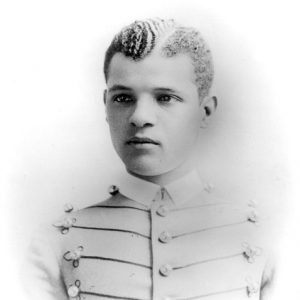

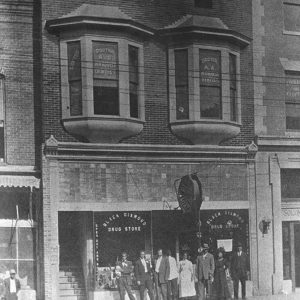

John Hanks Alexander was the second African-American graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point. Bruce Bennett, who served twice as Arkansas’s attorney general, became infamous for his part in a securities fraud scandal. Napoleon Bonaparte Houser was a prominent African-American physician who owned the Black Diamond Drug Store; he invested in and participated in many aspects of Helena’s growth. Roberta Evelyn Martin was a significant figure during gospel music’s golden age as a performer and publisher. Jimmy McCracklin was a renowned blues musician, singer, songwriter, and music industry entrepreneur. Richard Allin was a newspaper columnist perhaps most well known for directing humor at state legislators. DeWitt Jordan was a Black artist known for paintings that detailed the life of Black residents in the area.

Abraham Hugo Miller, born a slave, became a reverend, a businessman, and a legislator. At the peak of his business operations, he was considered the wealthiest black man in Arkansas. He married Eliza Ann Ross Miller, who became known as a businesswoman and an educator, as well as the first woman to build and operate a movie theater in Arkansas. She was inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame in 1999.

For additional information:

Green, E. G. “A Brief History of West Helena.” Phillips County Historical Quarterly 3 (June 1965): 20–22.

A History of the Jewish Community of Phillips, Lee, and Monroe Counties and Its Home Temple Beth El, Helena, Arkansas. Helena, AR: Temple Beth El Cemetery, 2024.

Kirkman, Dale. “Old Helena.” Phillips County Historical Quarterly 19 (December 1980 and March 1981): 73–87.

Kohl, Rhonda M. “’This Godforsaken Town’: Death and Disease at Helena, Arkansas, 1862–63.” Civil War History 50 (June 2004): 109–144.

Nixon, Jennifer. “Where History Runs DEEP.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. March 25, 2007, pp. 1H, 3H.

Rotenstein, David S. “Blue Ghosts in the Black Mecca: Appropriation and Erasure in Helena, Arkansas.” Journal of Urban Affairs 44, no. 6 (2022): 844–864.

Sabin, Warwick. “Delta Resurgence.” Arkansas Times. February 22, 2007, pp. 10–12.

Schieffler, G. David. “Unwriting the Freedom Narrative in the Trans-Mississippi: The Black Refugee Community at Helena, Arkansas, 1862–1863.” In Hundreds of Little Wars: Community, Conflict, and the Real Civil War, edited by G. David Schieffler and Matthew M. Stith. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2025

Snyder, Josh. “West Helena Struggles to Restore Water.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 29, 2024, pp. 1A, 3A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/jan/29/residents-in-parts-of-helena-west-helena-have/ (accessed January 29, 2024).

Whayne, Jeannie, and Willard B. Gatewood, eds. The Arkansas Delta: Land of Paradox. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Worley, Ted R. “Helena on the Mississippi.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 13 (Spring 1954): 1–15.

Steven Teske

CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Actress Deborah Benson is from Helena!