calsfoundation@cals.org

Garland County

| Region: | Southwest |

| County Seat: | Hot Springs |

| Established: | April 5, 1873 |

| Parent Counties: | Hot Spring, Montgomery, Saline, Clark |

| Population: | 100,180 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 677.64 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

9,023 |

15,328 |

18,773 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

27,271 |

25,785 |

36,031 |

41,664 |

47,102 |

46,697 |

54,131 |

70,531 |

73,397 |

88,068 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

96,024 |

100,180 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

78,837 |

78.7% |

| African American |

8,128 |

8.1% |

| American Indian |

802 |

0.8% |

| Asian |

972 |

1.0% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

71 |

0.1% |

| Some Other Race |

3,371 |

3.4% |

| Two or More Races |

7,999 |

8.0% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

7,047 |

7.0% |

| Population Density |

147.8 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$44,777 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$27,171 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

18.6% |

|

Garland County, in the heart of the Ouachita Mountains, is home to the nation’s first federal reservation, which later became Hot Springs National Park. It has a diverse economy supported by strong tourism, forestry, manufacturing, and regional medical facilities.

Pre-European Exploration

The first inhabitants of the area to be called Garland County arrived about 12,000 BC, and this region was occupied by native people until about AD 1600. Although they had left the area before the first white American pioneers arrived, artifacts indicate that the native residents were related to historic Caddo Indians.

Pioneer archaeologist Mark R. Harrington dug into several sites along the Ouachita River. At some locations, he found burned buildings buried under low mounds that were built in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries AD. At another location, his workers dug seventeen feet down through the accumulated remains at a site near the river. This site was used repeatedly by parties of hunters and foragers as a temporary camp. Many such camps were situated along creeks and rivers and near the bedrock novaculite outcrops in the hills.

For many thousands of years, Indians quarried novaculite from bedrock deposits in the hills around Hot Springs. This stone was desirable for spear points and other chipped tools and was traded widely throughout southwest Arkansas and neighboring regions for many centuries. Local tradition associates Indians with the hot springs in Garland County; although the residents of the area surely were aware of the springs, no historic evidence suggests that they enjoyed immersion in hot water.

European Exploration

Spanish explorers passed through Garland County in 1541, although no absolute proof exists to confirm local traditions that Hernando de Soto actually visited the hot springs. Local names such as Fourche a Loupe suggest the presence of French explorers in the eighteenth century. France claimed all of Arkansas between 1682 and 1762; in that year, they ceded Louisiana (including the area that became Garland County) to Spain.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

In 1800, a shift in European power restored to France the Spanish holdings in the Mississippi River Valley. On April 30, 1803, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and U.S. President Thomas Jefferson agreed on the Louisiana Purchase. For about three cents an acre, the future Garland County became part of a U.S. territory.

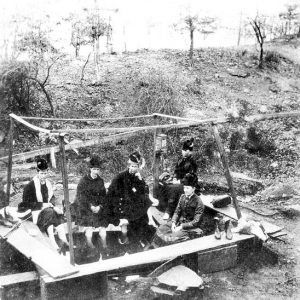

Jefferson had heard of the hot springs from a friend in Natchez, Mississippi, William Dunbar, a planter and amateur scientist. He asked Dunbar to lead an expedition into the Ouachita Mountains and report on the Indian tribes, minerals, and springs. Joined by his friend George Hunter, a chemist, and about a dozen soldiers, Dunbar arrived in Hot Springs in December 1804 and found “an open log-cabin and a few huts of split boards … for summer encampment … erected by persons resorting to the springs for the recovery of their health.” They studied the area for a little more than a month, then returned to report to Jefferson what they had found. Big Chalybeate Spring was referenced. This was the area’s first official American exploration, with reports that predated Lewis and Clark’s more famous expedition of the American West.

In 1807, Jean Pierre Emanuel Prudhomme, the ailing owner of a Red River plantation, heard about the healing hot waters from the Natchitoches Indians. He built the first real settlement at the springs and lived there for two years. Isaac Cates and John Percival, two trappers from Alabama, joined him there. Cates was mainly a trapper, but Percival envisioned a great future for the area and built log cabins to rent to the growing number of visitors to the springs.

On August 24, 1818, the Quapaw ceded the land around the hot springs to the United States. Also in 1818, Missouri subdivided Arkansas County into Clark, Hempstead, Lawrence, and Pulaski counties. It was from the original Clark and Pulaski counties that Garland County would be created years later.

In 1828, Ludovicus Belding, his wife, and children came from Massachusetts in a covered wagon to visit the springs. After a few months, he built a small hotel for visitors to the springs.

On April 20, 1832, four years before Arkansas gained statehood, President Andrew Jackson signed a bill making Hot Springs the first land reserved by the federal government for future recreational use by U.S. citizens. The ownership of the valuable land around the hot springs was fought over in the courts for almost twenty-five years between original claimants John C. Hale, Ludovicus Belding, John Percival, and Henry M. Rector. When the U.S. Supreme Court settled the dispute in 1877, the U.S. government owned the land as a national reservation.

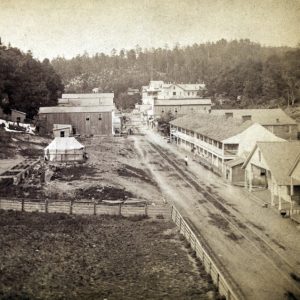

As it did for the Indians, word of the natural hot springs drew visitors from around the world, but the area’s remote location, in a time of rough roads and unreliable transportation, kept the county’s population sparse for years. The 1830 Census lists only 458 in Hot Spring County and eighty-four in Hot Springs Township. The 1860 Census lists 201 Hot Springs residents, but the Civil War reduced the population to just a few families at its end.

Civil War through Reconstruction

From May 6 to July 14, 1862, Hot Springs was the state capital when Governor Henry Massie Rector moved his staff and state records there to protect them from the Union troops marching on Little Rock (Pulaski County). Only one engagement of note took place in the area, the Skirmish at Farr’s Mill in 1864. The area that would become Garland County was never occupied by Union troops, but almost the entire population fled to Texas and Louisiana. The citizens feared not only the soldiers but the renegade bands that would terrorize and destroy much of the county.

Hot Springs, unlike many other Arkansas towns, rebuilt rapidly after the war. Residents grew tired of the daylong trip to the county seat in Rockport near Malvern (Hot Spring County) and got the legislature to establish Garland County, with its county seat in Hot Springs. It was named for Augustus H. Garland, who served as governor in 1874, U.S. senator from 1876 to 1885, and U.S. attorney general in 1885 under President Grover Cleveland. Garland County was created on April 5, 1873, from parts of Hot Spring, Montgomery, and Saline counties.

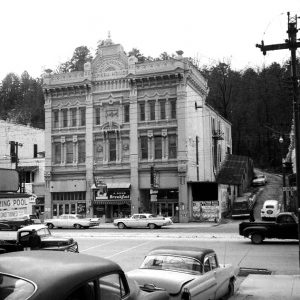

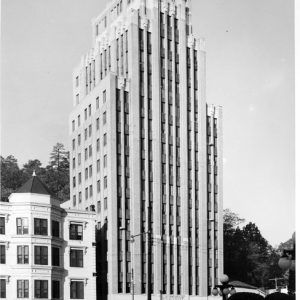

The governor named J. W. Jordan, Bennett Malone, and W. A. Moore to the board of supervisors, and they selected Hot Springs as its seat of justice. In 1882, the county converted a house downtown into the first courthouse. It was destroyed by fire in 1888, was rebuilt downtown and burned again in 1905. Later that year, the present location at Hawthorne and Ouachita streets was selected. On September 5, 1913, that structure, along with sixty blocks of the city, was severely damaged by another fire, but its frame remained and it was restored. In 1979, the Renaissance-inspired courthouse was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Post-Reconstruction through Early Twentieth Century

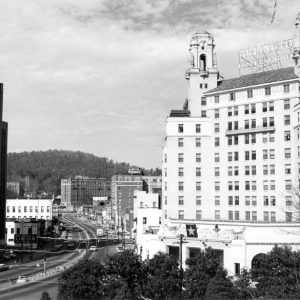

From 1873 to 1900, tremendous change occurred in the county. Two railroads were built, and large new resort hotels attracted many visitors. Major investments by businessmen including Samuel Wesley Fordyce changed the face of the county. A federally funded Army-Navy Hospital was constructed in Hot Springs in the 1880s. Racetracks and gambling flourished. The fight to control gambling in Hot Springs led to a shootout between the city police and the Garland County Sheriff’s Department in 1899.

Setbacks to the continued growth in the county included a smallpox outbreak and a blizzard, which both occurred in 1895. However, professional baseball teams began to use Hot Springs for spring training, and famous people from all walks of life followed. Hot Springs’s population reached almost 10,000.

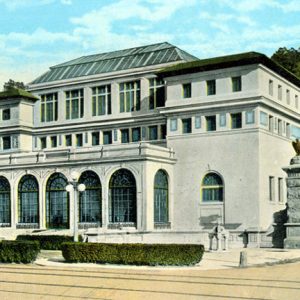

On March 4, 1921, the Hot Springs Reservation became a national park, and the county continued to grow. Though tourism and illegal gambling were the major forces that drove the county’s economy during this time, a huge timber industry by Dierks Forests, Inc., and the mining of novaculite contributed.

Boom towns appeared in the county during the late nineteenth century, including Bear, Blakely, and White Sulphur Springs. These communities were closely tied to either the timber or tourist industries, although Bear got its start due to unfounded rumors of precious metals in the area.

Multiple incidents of racial violence leading to a lynching took place in the county in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Will Norman, accused of killing an eleven-year-old white girl, was killed in 1913. After allegedly arguing with several white boys, Will Warren was killed and his house burned in rural Garland County. Gilbert Harris lost his life to a lynch mob after being accused of killing a white man in 1922. In addition, there was a 1919 case of nightriding in the Little Georgia that resulted in the Arkansas Supreme Court case of Housley v. State.

World War II through Modern Era

Former service members returned to the county after World War II and challenged the existing political machine in the county. They were ultimately successful in an effort known as the GI Revolt, winning multiple county offices. This led to the election of Sid McMath as prosecuting attorney for the district that contained Garland County and his later election as governor.

Hot Springs is the county’s largest city. Other towns include Mountain Pine, an incorporated city with a population of 770 in 2010, and Lonsdale and Fountain Lake, with populations of 94 and 503, respectively. Large industries began adding to the county’s economic base after World War II began, including Reynolds Metal Company in 1942, Alliance Rubber Company in 1954, Norris Dispensers, Inc., in 1957, and Lake Catherine Footwear in 1960.

The gated community of Hot Springs Village, which straddles the Garland-Saline county line, was established in 1970 by John A. Cooper Sr., who had previously created the communities of Cherokee Village (Sharp County) and Bella Vista (Benton County). The town is known for its recreational facilities, especially golf courses that constitute a major tourist attraction. Jessieville is an unincorporated community located northwest of Hot Springs Village.

Garland County is a unique recreational resort and retirement area with its mountains, forests, and three manmade recreational lakes: Catherine, Hamilton, and Ouachita (the state’s largest). The construction of the dams that formed the lakes led to the evacuation of several communities. Following the construction of the Blakely Mountain Dam in the 1950s, the communities of Buckville and Cedar Glades were flooded by the newly formed Lake Ouachita. The Buckville Cemetery is the last remaining part of that community. The construction of Carpenter Dam led to the creation of Lake Hamilton and the construction of condominiums, restaurants, and other tourist facilities along the shoreline.

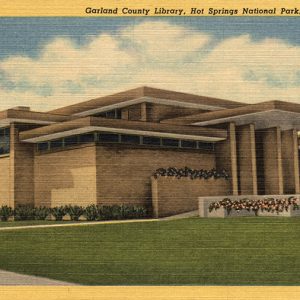

Hot Springs National Park is the oldest area protected by the National Park System. Bathhouse Row is a National Historic Landmark District. Attractions such as the Magic Springs amusement park, quartz crystal mines, the Mid-America Science Museum, Oaklawn Racing Casino Resort, Garvan Woodlands Garden, and Hot Springs Mountain Tower draw thousands of visitors annually. National Park College and the Arkansas School for Mathematics, Science, and the Arts are located in Hot Springs.

For additional information:

Anthony, Isabel, ed. Garland County, Arkansas: Our History and Heritage. Hot Springs, AR: Garland County Historical Society, 2009.

Ashmore, Harry S. Arkansas—A History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1978.

Blaeuer, Mark. Didn’t All the Indians Come Here? Separating Fact from Fiction at Hot Springs National Park. Fort Washington, PA: Eastern National, 2007.

Brown, Dee. The American Spa. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1982.

Hudgins, Mary D. “Origins of a County Called Garland.” The Record 14 (1973): 1–12.

The Record. Hot Springs, AR: Garland County Historical Society (1960–).

Charles William Cunning

Hot Springs, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Henderson State University

I was born and grew up in Hot Springs (Garland County) and am a member of the Garland County Historical Society. Here are some of the events I think are crucial to the county’s history: 1880s: Norman McLeod established Happy Hollow Amusement Park; 1887: the Army-Navy Hospital (frame buildings) was built; 1933: renovation of Army-Navy Hospital (brick building); 1876: Joseph Reynolds established a narrow-gauge railroad from Malvern to Hot Springs. In my opinion, it was one of the most important events in the city’s history. It opened up Hot Springs to the world.; 1889: “The Diamond Joe Line” was converted to regular gauge line