calsfoundation@cals.org

Hot Springs Smallpox Outbreak of 1895

In the early months of 1895, Hot Springs (Garland County) suffered through a blizzard, numerous fires, and a smallpox outbreak. These collective disasters left the community economically crippled.

The Blizzard of 1895 that swept across much of the country in late January/early February had made travel to the spa resort town impossible during what was normally its busy season. By mid-February, travel had resumed, and visitors soon filled up the town. Then, a series of unexplained fires started flaring up across the city, culminating in a large conflagration in the early hours of Friday, February 22. The fire started around 3:30 a.m. and, within minutes, it had engulfed four and a half blocks of businesses and residential buildings while thousands stood watching, leaving many with only the nightclothes they wore.

As the sun came up that day, visitors and residents alike were met by the horrifying sight of smallpox flags. Although local officials tried to allay public fears on Saturday, by Sunday rumors were outpacing official reports, and visitors by the hundreds had started packing up to escape.

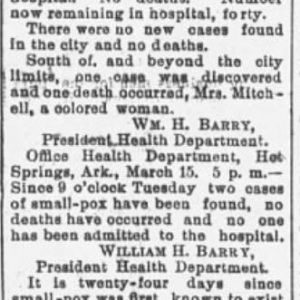

In an effort to prevent a panic—and even more loss to the city’s revenue—city health officer Dr. W. H. Barry issued a bulletin on Sunday, stating that there was only one case of smallpox. But even as he was getting ready to issue his Sunday bulletin, authorities in the nearby town of Malvern (Hot Spring County) issued a quarantine against Hot Springs that morning. Also, a correspondent with the Arkansas Gazette reported on Monday that there were at least twenty-five cases of smallpox in Hot Springs.

Then more rumors began to spread on Tuesday. They stated that, at the time Dr. Barry was preparing his bulletin, “there were 75 cases being treated.” Thus, frightened by the rumors, and with less than perfect application of quarantine laws, hundreds of visitors dashed to the “through” train to St. Louis, the only train allowed to breach the Malvern quarantine. When the passengers arrived in St. Louis, that city’s papers quickly printed stories based solely on rumors that were then sent out across the country. The papers also failed to mention whether any of the passengers from Hot Springs actually had smallpox.

In an attempt to stem the tide of rumors, Dr. Barry issued a bulletin on Thursday evening only hours after the St. Louis passenger report broke. As his report was in out-of-state papers the next morning, it is likely that he sent out his bulletin by telegraph. From this official communication, it is evident that Dr. Barry took what actions he could to suppress the smallpox outbreak, including issuing a threat against physicians who failed to report cases of smallpox. His statements that “a few physicians were careless about reporting” cases of smallpox may further help explain the inconsistency between the number of cases officially reported and the number reported from rumor. The inaccurate reporting of cases also helps explain the delay of an official response.

Despite all the panic and lack of cooperation in some quarters, it appears that the physicians involved in suppressing the epidemic acquitted themselves well. They organized and then set about to quarantine, inoculate, inspect, and contain. Eventually the outbreak played out, although it left in its wake a monumental economic hardship that affected everyone in the community.

For additional information:

Percefull, Janis K. “A Public Health Response: 1895 Spa City Smallpox Epidemic.” The Record 51 (2010): 181–194.

Proceedings of the City of Hot Springs, Arkansas. Vol. 6, pp. 412, 417–423.

“The Yellow Death Smallpox Epidemic at Hot Springs, Arkansas—Tourists Fleeing for Life.” Salt Lake Herald, February 28, 1895, p. 1.

Janis Percefull

Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.