calsfoundation@cals.org

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC)

A brainchild of newly elected President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the New Deal program the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) began in 1933 with two purposes: to provide outdoor employment to Depression-idled young men and to accomplish badly needed work in the protection, improvement, and development of the country’s natural resources. Camps housing 200 men each were established in every state: 1,468 in September 1933, 2,635 in September 1935, and, because of the improving economy, down to 800 by January 1, 1942. During this period, seventy-seven companies undertook 106 projects located in Arkansas.

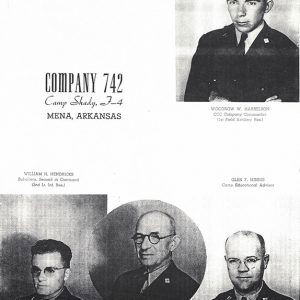

Variously called, “Roosevelt’s Tree Army,” “Tree Troopers,” “Soil Soldiers,” and the “Three-Cs Boys,” the CCC was the result of Senate Bill 8.598, which was signed into law on March 31, 1933. Reserve officers of the army ran the camps, which provided food, clothing, shelter, education, and morale. The Department of Labor selected the young men through state agencies and welfare offices. Those enrolled had to be between eighteen and twenty-five years old (later adjusted to seventeen through twenty-eight), United States citizens, of good moral character, out of school, and in need of employment. Enrollees could volunteer for a six-month period and reenroll each six months for up to two years. Later in 1933, separate camps were authorized for veterans of the Spanish-American War and World War I. Their duties were assigned according to their age and physical condition without restrictions on marital status or age. Arkansas had four veteran camps.

The Department of Agriculture and the Department of the Interior planned the jobs and furnished project supervisors and technicians for the field work. The department that needed work done had charge of the job sites.

CCC workers performed over 100 types of work, from planting trees (over three billion) to building parks (more than 800 nationwide) to developing over 28,000 miles of hiking trails. They also saved forty million acres from erosion and built 47,000 bridges. After nine years and three million enrollees, the CCC was dissolved by Congress on July 1, 1942, with many of those still enrolled entering World War II. More than 200,000 Arkansas natives had served in camps from coast to coast.

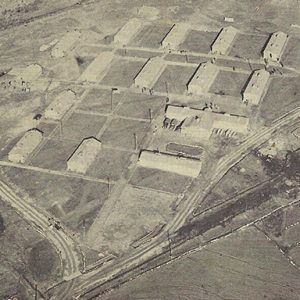

CCC companies were housed in forty-man barracks. Camps resembled small villages and included bathhouses, electric lighting plants, kitchens, storage, infirmaries, recreation halls (later, educational buildings), a softball or baseball diamond, and sometimes a football field. Cash allowances were $30 a month, and mandatory allotment checks of $25 were sent back to families of the men. Of the $5 each man kept, $1 went into the company fund, and they could buy $1 worth of coupons (twenty at five cents each) for the canteen. Promising fellows were promoted to assistant leaders and leaders at $36 and $45 respectively. The workload was eight hours a day, five days a week. Evenings were free except for compulsory (on their own time) training in First Aid and reading classes for the illiterate.

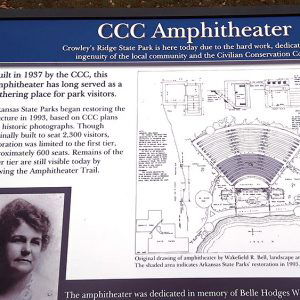

Most CCC projects in Arkansas were in national forests or on state-owned property. The fledgling state parks system benefited greatly; the work program created roads, trails, lodges, cabins, campgrounds, amphitheaters, bathhouses, picnic pavilions, and beaches at six locations in four different regions of the state: Petit Jean, Mount Nebo, Crowley’s Ridge, Devil’s Den, Lake Catherine, and Buffalo Point.

Petit Jean, Arkansas’s first state park, was occupied by Company 1781-V (Arkansas veterans) during mid-July 1933. The CCC-built lodge overlooking Cedar Creek Canyon was named in honor of the late National Park Service director Stephen T. Mather, who had encouraged the state to establish Petit Jean State Park in 1923. Natural stone and log cabins were built, along with hiking trails and bridges. These structures remain the focal point of Petit Jean State Park.

Mount Nebo State Park’s CCC camp, Company 1780-V, led by Captain H. L. Eagan, brought twenty tons of equipment and 186 veteran enrollees 1,350 feet up the mountain from the Dardanelle (Yell County) train station. These men were often twenty years older than the average CCC recruit.

Crowley’s Ridge State Park, near Paragould (Greene County), was manned by CCC Camp 1729 returning from duty in Oregon. The park site was the pioneer homestead of Benjamin Crowley. Companies 1729, 2746, and 4733 all participated in the building of this park, which included a spring-fed lake, swimming beach, two-story bathhouse, pavilion, campgrounds, picnic sites and nature trails—one of which winds around Lake Ponder and today features exhibits about the CCC work: roads, bridges, and restrooms. To aid in soil conservation, more than 11,000 trees and shrubs were added during 1935. The park was dedicated in June 1938.

Company 797, made up of men from North Dakota under the command of Lieutenant J. C. Bakken, made the trip to Arkansas via rail in late 1933. They moved into Devil’s Den State Park with a six-month assignment to construct a good gravel road from West Fork (Washington County) to Devil’s Den. Companies 757, 3777, and 3795 also worked at this site constructing a massive stone dam on Lee’s Creek, as well as building native stone and log cabins, campgrounds, offices, and a restaurant.

Lake Catherine, covering 2,500 acres between Hot Springs (Garland County) and Malvern (Hot Spring County), became Lake Catherine State Park in 1937. In 1924, the Arkansas Power and Light Company (AP&L) created the lake by impounding the Ouachita River for electric generation. AP&L’s president, Harvey Couch, then donated to the state more than 2,000 acres at the lake, named for Couch’s daughter. Company 3777 arrived at Lake Catherine in 1938. Organized in 1935 at Devil’s Den, it had later moved to Boyle Park in Little Rock (Pulaski County). When they finished at Boyle Park, the company transferred to Lake Catherine, where the young men built cabins with stone walls, bridges, a fishermen’s barracks, and a lodge, as well as other park facilities.

Other CCC camps included one at Mulberry and a soil-conservation camp in Pocahontas (Randolph County). At one camp near Harrison (Boone County), the crews worked on a project near Eureka Springs (Carroll County), Lake Leatherwood Park. Composed of 1,600 acres, a 100-acre lake, and a large limestone dam, this park is one of the largest municipal parks in the United States.

In June 1933, Company 744 set up camp in the soon-to-be ghost town of Graysonia (Clark County) on the Antoine River. The enrollees, under the supervision of George Wells, a former Clark County judge, lived in a spacious two-story frame, no-longer-used schoolhouse; the students were schooled in the smaller Straightway Church in town.

Camp Hedges, Company 743, in the Sylamore District of the Ozark National Forest, was located between Calico Rock (Izard County) and Mountain View (Stone County). It supplied men who built roads, bridges, firebreaks, and the original facilities at Blanchard Springs Caverns, including log cabins, campsites, a recreation hall, and other stone structures. The enrollees also fought forest fires and performed conservation work. In addition, the men of Company 3784 of Camp Shiloh, located in Russellville (Pope County) during 1935, worked on forestry projects north of that city.

In June 1935, Camp 3782 was established on a mountain south of Heber Springs (Cleburne County) for soil conservation efforts. Truckloads of grass sod were hauled to farms in the region to help establish cattle operations. The CCC grass is still producing, except for the acreage now covered by Greers Ferry Lake. Other efforts included fencing and pond-bank stabilization.

Camp 1750, set up in the forest country of Crossett (Ashley County), built roads and bridges, and fought fires.

Camp Sage, Company 3780, was located at Stella near Melbourne (Izard County). It was built in 1935, situated on a hill overlooking a rural area, and held from 175 to 200 people at its peak. A fire-watch tower stood adjacent to the camp. Work activities were connected with forest husbandry and soil conservation: building forest roads, stringing telephone lines, building a side camp, drainage control, and containment of forest fires. Later, some of the roads were converted to county roads. During the last half of 1941, activity dwindled; the side camp shut down, and enlistments declined. By November, Camp Sage was disbanded.

One unique CCC side camp, the “floating camp” of BF-2, was situated at Jacks Bay in Arkansas County. There, the enrollees were African American rather than white, and they were housed in floating government quarterboats rather than in barracks or tent camps. The camp at Jacks Bay was occupied from January 1936 until May 1938.

In the CCC Act of 1937, the Corps ceased being primarily a relief agency. On June 30, 1939, it became part of the Federal Security Agency, and in 1942, the CCC objectives shifted to war efforts and victory. With the advent of World War II, the program ceased in 1943, but not before three million men experienced changes in their lives that would hold them in good stead in the future. One man, who grew up in Blytheville (Mississippi County) and enrolled in a camp at St. Charles (Arkansas County) that was ultimately disbanded, summed up what many men echoed: “I learned more during those two years in the CCC than I learned in the next ten. I went in a boy, came out a man. Went in ragged, hungry, ashamed and defeated, came out filled with confidence and ready to challenge the world.”

The ones who stayed in the CCC gained weight and enjoyed improved health and morale. They learned good work habits, skills, and attitudes. Many rose through the ranks of business and industry. As the economy picked up, more men were able to find jobs in their local areas. As the war threatened, many enlisted. Enrollments dipped, and many camps disbanded.

At least four projects in Arkansas can still be seen. A CCC cabin and Mather Lodge at Petit Jean State Park, and CCC pavilions at Crowley’s Ridge State Park and Devil’s Den State Park. A CCC statue (No. 15) was dedicated on June 30, 2002, at Devil’s Den.

For additional information:

Afsordeh, Danielle. “Beyond the Surface: Little Rock’s Unseen CCC Parkitecture.” Pulaski County Historical Review 73 (Winter 2025): 104–108.

Barnett, Paula Harmon. “Civilian Conservation Corps Camps #4733.” Rivers and Roads and Points in Between 32 (2008): 29–32.

Biggs, Jackie Sue. “Solon Cannon Remembers CCC Co. 768 at Blue Mountain.” Wagon Wheels 14 (Winter 1994): 5–9.

“Camp Ozone.” Johnson County Historical Society Journal 23 (April 1997): 7–11.

“Civilian Conservation Corps.” Arkansas State Parks. https://www.arkansasstateparks.com/parks/historic-parks/civilian-conservation-corps (accessed July 28, 2023).

Civilian Conservation Corps Camps Arkansas. https://ccclegacy.org/ccc-camp-lists/ccc-camps-arkansas/ (accessed May 22, 2024).

The Civilian Conservation Corps in Arkansas, online exhibit of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture. https://ualrexhibits.org/ccc/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Galloway, Norma Jean. “Company 746, Civilian Conservation Corps.” Faulkner Facts and Fiddlings 15 (Summer 1973): 42–50.

Goetz, Kary W. “The Legacy of the Civilian Conservation Corps in Arkansas: A Survey of Resources.” The Record (2019): 6.1–6.14.

Hanor, Bert. “CCC Camps in Garland County, 1933–1937.” The Record 15 (1974): 63–73.

Honnoll, W. Danny. “The Civilian Conservation Corps Camp 3783 at Jonesboro.” Craighead County Historical Society Quarterly 57 (April 2019): 3–16.

———“The Civilian Conservation Corps of Craighead County.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 32 (April 1998): 3–10.

Howard, Dixie Covington. “Remembering the CCC.” Grassroots: The Journal of the Grant County Museum 11 (December 1991): 2–17.

Jenkins, Jan. “The Civilian Conservation Corps in Drew County: ‘Roosevelt’s Tree Army’ and Camp Monticello.” Drew County Historical Journal 10 (1995): 43–47.

Jones, Paul E. The Forgotten Boys of the Civilian Conservation Corps, Who Enlisted as Boys and Were Discharged as Men. Eldorado, IL: Rocky’s Printing, 2004.

Kirk, John A. Beyond Little Rock: The Origins and Legacies of the Central High Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

Lampkin, Sheila. “The Civilian Conservation Corps in Drew County: Memories of Camp Monticello.” Drew County Historical Journal 21 (2006): 29–36.

May, Joe, ed. “Graysonia CCC Camp Mementoes.” The Old Time Chronicle 16 (Mid-Winter 2004): 12.

McCarty, Joey. “Civilian Conservation Corps in Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1977.

Murphy, Michael. “The Rise and Fall of Fire Lookout Towers in Faulkner County: Construction by Company 4748 of the Civilian Conservation Corps, 1937–1939.” Faulkner Facts and Fiddlings 45 (Summer/Fall/Winter 2002): 29–68.

Serrano-Wilks, Joy. “Interview with John H. Baker, Corley Camp 747.” Wagon Wheels 15 (Spring 1995): 32–40.

Sillavan, Don. “CCC Camp Alton, 1935–1942: A Fun Place on a Hill.” Journal of the Hempstead County Historical Society 13 (Spring 1989): 34–44.

Stanton, Lindsey. “The Civilian Conservation Corps and ‘Camp Sheridan.’” Grassroots: The Journal of the Grant County Museum 43 (August 2022): 13–17.

Tim, M. J. “Camp Chaplin: A ‘Shot in the Arm’ for Carroll County’s 1935–1940 Economy.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly 26 (Winter 1981–1982): 11–14.

Wilson, Jarvis. “Camp Sage–CCC.” Izard County Historian 20 (January 1989): 3–22.

Yount, Sheila. “Gateways to Nature: The CCC’s Enduring Legacy.” Arkansas Living, February 2019, pp. 8–10, 12, 14.

Patricia Paulus Laster

Benton, Arkansas

According to my family’s lore, my paternal grandfather, Raymond Nesbit, a WWI veteran, worked with the CCC at both Petit Jean and Mount Nebo.

My grandfather worked at the CCC camp on Petit Jean and was a cook. He lived in Ada Valley and would walk from his home up to the CCC camp. Does anyone have access to all the men’s names who worked there? There should be a marker built for them with their names on it.

My dad, Gerad J. Neihouse, was in the Ozone, Arkansas, camp. I think he was in from 1938 until 1940. He was from Coal Hill, Arkansas. He took me to the camp site around 2000, and the foundation for the camp was still there and also a small pond in the shape of the state of Arkansas. Dad also would go to the reunions the CCC had. I believe he also became friends with a gentleman who was doing research or writing a book about the CCC; this was in the 1990s. My dad passed away in 2011, and he’s buried at the National Cemetery in Fort Smith, Arkansas.