calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas National Guard

aka: Arkansas Department of the Military

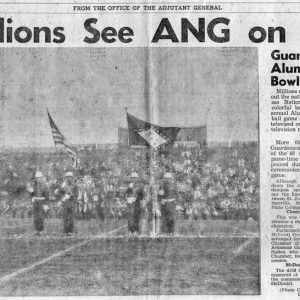

The Arkansas National Guard consists of the Arkansas Army National Guard and the Arkansas Air National Guard. The Arkansas Guard is commanded by the adjutant general, who is appointed by the governor. While some guard members work full time in their military jobs, most have full-time civilian careers. They conduct their military training a minimum of one weekend a month and an additional fifteen days a year. The Arkansas National Guard and its militia predecessor have furnished troops for every war the United States has fought except Vietnam, when the federal government called few of the country’s National Guard units into active duty.

The federal government dictates the types of units and their size and equipment, and all guard units are subject to the call of the president and of a state’s governor. This “dual status” makes the guard unique among the nation’s military forces.

The Arkansas National Guard 2023 Posture Statement stated that there were 8,706 members of the National Guard—1,956 air and 6,750 army. The full-time combined force totaled 2,134. This personnel included men and women from every county in the state and more than 600 residing out of state. Total state and federal expenditures in 2023 were over $425,770,746, with 97.3% of the total operational budget being provided by the federal government.

The Arkansas National Guard and the Arkansas Army National Guard headquarters are at Camp Joseph T. Robinson near North Little Rock (Pulaski County). The Arkansas Air National Guard is headquartered at Little Rock Air Force Base near Jacksonville (Pulaski County). The National Guard has four major training sites: Robinson Maneuver Training Center at Camp Robinson, Little Rock Air Force Base, Fort Chaffee Joint Maneuver Training Center in Fort Smith (Sebastian County), and Ebbing Air National Guard Base in Fort Smith. Housed at the Army National Guard headquarters at Camp Robinson are the Thirty-ninth Infantry Brigade Combat Team, the Seventy-seventh Theater Aviation Brigade, and the Eighty-seventh Troop Command. Headquartered in Fayetteville (Washington County) is the 142nd Field Artillery Brigade. The 189th Airlift Wing is headquartered at the Little Rock Air Force Base, and the 188th Wing is headquartered at Ebbing Air National Guard Base. Smaller units operate in dozens of locations across the state.

The Arkansas National Guard traces its roots to 1804. That year, a set of laws was formulated to govern the District of Missouri, including what is now Arkansas. One law established a requirement for a militia. The requirement was reinforced when Arkansas became a territory. The law creating Arkansas Territory provided that the governor would command the militia and appoint its officers. Despite their efforts, territorial governors had difficulty establishing a strong militia. A major factor was the scattered nature of the population and the lack of good roads. Another may have been the pioneer nature of the majority of settlers that led them to be wary of any organization with a “ruling class” of governor-appointed officers.

However, when the need arose, the Arkansas territorial militia responded to a call for service. The earliest record of the use of territorial militia in Arkansas was in 1828, when Governor George Izard dispatched Adjutant General William Rector to look into reported troubles between the local settlers and the Delaware and Shawnee in southwest Arkansas Territory. When discussions failed to resolve the problem, Rector called out members of the Miller County militia. The issue was resolved without bloodshed.

Another example is at the beginning of statehood in 1836. The U.S. Army had moved forces from the Native American lands west of Arkansas Territory to fight the Seminole in Florida. Nine Arkansas militia companies formed the First Regiment of Arkansas Mounted Gunmen and were mustered into federal service on August 9. They spent six months patrolling the border of the United States and the new republic of Texas.

The first time Arkansas militia units were called to active duty for combat was in 1846 for service in the Mexican War. The most notable unit was the Arkansas Regiment of Mounted Volunteers, which fought in the battle of Buena Vista on February 22–23, 1847. Eighteen members of the Arkansas regiment were killed, including the commander, Colonel Archibald Yell. The battle ended when the Mexican army retreated during the night of February 23.

After the war with Mexico, interest in the militia waned and did not rekindle until the approach of the Civil War. Militia forces forced the evacuation of Federal troops from the Little Rock Arsenal in February 1861. With the shelling of Fort Sumter in April 1861, interest in forming military units reached a fever pitch. Large numbers of Arkansans served in the Confederate army; a smaller number, mostly from northwest Arkansas, served in the Union army.

The end of the Civil War and the passage of the Reconstruction Act in 1867 resulted in martial law being imposed in Arkansas. The Confederate veterans, attempting to reestablish a life in Arkansas as they knew it before the war, were prevented from serving in the state militia. The militia established by the Reconstruction government consisted primarily of Black enlisted soldiers, many veterans of the Union army. Armed conflict between these two groups forced Governor Powell Clayton to impose martial law in Arkansas in November 1868. While martial law ended in Arkansas in March 1869, armed clashes between the two groups continued for the next five years, most notably in Pope County in 1872.

The end of Reconstruction in Arkansas, marked by the end of the Brooks-Baxter War, gave rise to a general indifference toward the militia, with few units actively training. Like the period after the war with Mexico, it took another national armed conflict to interest Arkansans in the militia.

For the Spanish-American War in 1898, Arkansas furnished the First and Second Regiments. Both were stationed at Chickamauga Park, Georgia, and the Second Regiment later went to Anniston, Alabama. Neither regiment saw combat. During the Mexican Border Expedition of 1916, the same two regiments were stationed at Deming, New Mexico. While there, they conducted training that would prove valuable. When the United States entered World War I, the First and Second Regiments had been home from New Mexico less than two months. Both regiments would wind up at Camp Beauregard, Louisiana. The First was redesignated the 153rd Infantry Regiment, and the Second became the 142nd Field Artillery Regiment. Both were part of the Thirty-ninth Division and deployed to France, but neither was in combat.

All the Arkansas Guard units were called to active duty before World War II as the United States took steps to prepare for the increasingly global conflict. The 153rd wound up stationed at several locations in Alaska. The 142nd Field Artillery was reorganized, and its units fought in France, Germany, and Italy. The 154th Fighter Squadron and the 206th Coast Artillery (anti-aircraft) had been added to the Arkansas Guard structure in the 1920s. The 154th flew combat missions from North Africa and Italy in a variety of aircraft, including the P-38 and P-51. The 206th was assigned to Dutch Harbor, Alaska, and helped defend against the Japanese attack on Dutch Harbor in June 1942 in what has become known as the Williwaw War.

The Korean War saw several Arkansas National Guard units called to duty. Most notable were the 154th Fighter Squadron and the 936th and 937th Field Artillery Battalions. The 154th turned in its World War II–era P-51 aircraft and converted to the F-84 jet fighter. The squadron flew missions from Japan and later South Korea. The two artillery battalions, which had fought in World War II after the reorganization of the old 142nd, provided fire support to U.S. and United Nations forces.

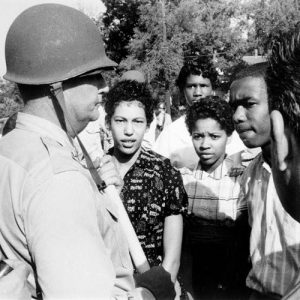

The next time the Arkansas Guard was called to duty was in 1957. Governor Orval Faubus initially called the Arkansas National Guard to duty to prevent the Little Rock Nine from desegregating Little Rock Central High School. President Dwight Eisenhower then called the guard to federal duty to ensure the safe entry of the Black students.

Any concerns about the guard’s willingness to carry out the president’s orders were put to rest with this section of its operations order for duty at Central High: “Our mission is to enforce the orders of the Federal Courts with respect to the attendance at the public schools of Little Rock of all those who are properly enrolled, and to maintain law and order while doing so….Our individual feelings towards those court orders should have no influence on our execution of the mission.” The professionalism of the Arkansas Guard units in carrying out their responsibilities was instrumental in maintaining the peace in an emotionally charged situation.

In 1990, the Arkansas Army National Guard had thirteen units called into federal service during Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm, and members of ten units of the Arkansas Air National Guard were called up. More than 3,400 Arkansas Guard soldiers were called up, the second-highest percentage of any state or territory. Nine of the army guard units served in combat, including the 142nd Field Artillery Brigade, the only National Guard artillery brigade called to active duty in the Persian Gulf War. The largest unit to serve has been the Thirty-ninth Infantry Brigade, which spent a year in Iraq as part of the First Cavalry Division. Fifteen members of the Thirty-ninth were killed in action during that mobilization.

At the state level, the Arkansas National Guard has been called out for virtually every natural disaster in the past century, including floods, tornadoes, and ice storms. The guard responded to the needs of people in Mississippi and Louisiana in the aftermath of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005; Arkansas was one of the first states to respond and was the last state to withdraw from Louisiana. The Arkansas National Guard is also heavily involved in drug awareness and eradication programs, including prescription drug take-backs and distribution of naloxene kits for overdoses, and began operating two youth programs in the late twentieth century.

Some notable deployments in 2023 were soldiers from the 875th Engineer Battalion on a federal mission to southern Texas in support of U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, the welcoming home of the 149th Aviation Battalion deployed to Iraq and Syria, members of the Thirty-ninth Brigade sent to Germany to train Ukrainian troops, members of the 216th Military Police Company deployed to Romania to provide security for American and NATO allies operating from a base there, and troops sent to southwest Asia in support of Operation Spartan Shield to promote regional self-reliance and increase security among partner nations. In Arkansas in 2023, members were activated to distribute drinking water to Wilmar (Drew County), Helena-West Helena (Phillips County), and Sparkman (Dallas County) while those communities worked to restore regular services. The Thirty-ninth IBCT was activated for winter storm response to provide support to the Arkansas State Police, as well as aid and recovery for the local communities. In addition, sixty soldiers were deployed to Guatemala to conduct a multi-nation exercise with Guatemala and other Central American nations to enhance basic infantry skills, small-unit tactics, and mission planning.

Both the Arkansas Army National Guard and the Arkansas Air National Guard continue to upgrade their equipment and training so they can respond to the call of duty, whether from the governor or the president. As part of the large-scale reorganization of state government under Act 910 of 2019, the Arkansas Department of the Military was created as one of fifteen cabinet-level departments. This new department was headed by sitting Adjutant General Mark Berry, who became a cabinet secretary while remaining head of the Arkansas National Guard, as the two entities appear to overlap completely.

For additional information:

Arkansas National Guard. https://arkansas.nationalguard.mil/ (accessed February 24, 2026).

Arkansas National Guard African American Pioneers: Untold Stories. North Little Rock: Arkansas National Guard Museum, 2023.

Arkansas National Guard Museum. http://www.arngmuseum.com (accessed February 24, 2026).

Arkansas National Guard 2023 Posture Statement. https://arkansas.nationalguard.mil/Portals/29/2023%20Posture%20Statement_web.pdf (accessed February 23, 2026).

Dillard, Tom W. “‘An Arduous Task to Perform’: Organizing the Territorial Arkansas Militia.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Summer 1982): 174–190.

Forgotten: The Arkansas Korean War Project. CALS Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. https://robertslibrary.org/collection/korean-war/home/ (accessed February 24, 2026).

Goldstein, Donald M., and Katherine V. Dillon. The Williwaw War: The Arkansas National Guard in the Aleutians in World War II. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Maxwell, William E. “A History of the 206th Coast Artillery (Anti-Aircraft) Regiment of the Arkansas National Guard in the Second World War.” MA thesis, University of Central Arkansas, 1992.

Steve Rucker

Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.