calsfoundation@cals.org

Caddo Nation

Caddo Indians enter written history in chronicles of the Hernando de Soto expedition, which describe encounters during the Spanish passage through southwest Arkansas. When the Spaniards crossed the threshold to Caddo country on June 20, 1542, they entered a nation uniquely distinguished by language, social structure, tradition, and way of life.

Caddo people were sedentary farmers, salt makers, hunters, traders, craftsmen, and creators of exquisite pottery who buried their dead in mounds and cemeteries with solemn ritual and a belief that the dead traveled to a world beyond this. Caddo language was unlike any spoken by other groups the Spaniards met as they explored northeast Arkansas and the Southern states east of the Mississippi River. Caddo communities—called villages or towns in the de Soto chronicles and often referred to as tribes or bands by later writers—were actually related farmsteads secluded and separated by gardens and woodland. Relatives lived together in one or more houses on a farmstead. Their homes, circular constructions with a frame of poles bound at the top to make an oval, were thatched with long grass. Early observers thought the houses resembled beehives. An outdoor work platform or arbor, a drying rack, and an elevated, thatched domed structure used for storing corn usually stood near the houses. In some compounds, the houses were rectangular, made of vertical timbers stuck into the ground, daubed with mud, and covered by roofs of bark or grass. The social settlement pattern of dispersed Caddo farmsteads formed communities that often stretched for miles around a mound or a group of mounds that marked the ceremonial center.

Each Caddo community had a principal leader generally named “chief” by English speakers, cacique by the Spanish, and caddi by the Caddo. The caddi position was hereditary. A boy in line for the title had years of tutoring. By the time he was deemed mature enough to be caddi, he was well schooled for his duty to keep order in his community settlement and contribute to the peace of the Caddo Nation. He set the time for the building of a new house, approved marriages, called assemblies of the elders for major decisions, hosted feasts, organized official welcomes for visitors, was a sponsor and officiant at planting and harvest ceremonies, conducted peacemaking ceremonies, supervised the division of gifts from foreign emissaries, conducted councils for raising a war party, and hosted victory celebrations.

Only a few spiritual leaders lived at the mound centers. One called the chenesi (xeneci in Spanish documents) held power and prestige superior to that of a caddi. No Caddo dared cause his displeasure. Except for special visits or a brief walk, the chenesi remained in his house built on a flat-top mound while the people provided for all his needs. The grand chenesi communicated with Ayo-Caddi-Amay, “Great Leader Above,” and advised the people whether their conduct was good or bad. He was guardian of the sacred fire, which was sheltered in a special house near the one occupied by the chenesi. When a chenesi died, his nearest male blood kin succeeded him.

“There are at least twenty ceremonial centers, each with from one to eleven mounds, distributed in a forty-mile-wide band along the general route that the Spaniards must have taken from Arkadelphia, Arkansas, towards Texarkana and the Red River Valley,” notes Frank E. Schambach of the Arkansas Archeological Survey. “Many of them were in use during the sixteenth century, so the Spanish were probably always within twenty miles of an active temple mound, whether they knew it or not, and they must have seen farmsteads and other types of compounds everywhere.”

Hernando de Soto died a month before his army, then led by Luís de Moscoso, entered Caddo country with about half of the army’s original force of 600 soldiers and only forty of the 200 horses it once had. The entourage still had 500 captive Indians, a herd of hogs, and a pack of hounds trained to attack and kill Indians. Depleted and disillusioned, they no longer sought riches; they were instead looking for food and supplies for survival and for guides to direct them overland to New Spain (Mexico).

A reconstruction of the route described in de Soto chronicles locates the army’s entrance to Caddo country on the Ouachita River between Malvern (Hot Spring County) and Arkadelphia (Clark County). Near a small “town,” they stopped to make salt from “briny water” that state archaeologist Ann Early identifies as a site on the Saline Bayou. The highly productive salt springs at Bayou Sel became the site of the earliest salt works established by Europeans in Arkansas. Southwest Arkansas has many salt sites, and the Spaniards likely followed a trail used by generations of Caddo salt makers.

The Caddo closely watched paths leading to their communities and customarily sent a small group of men to welcome, or determine the intent of, approaching visitors. Somewhere near Nashville (Howard County), fifteen Caddo carrying gifts of skins, fish, and roasted venison waited for the Spaniards, although the people of the community had already moved out of harm’s way. The Spaniards camped in an empty “town” but found another major salt site and a plentiful supply of corn while making forays into the neighborhood, taking captives, and plundering farmstead granaries.

Moscoso continued to follow an overland salt trail and led the army into the Red River valley north of Texarkana (Miller County) near Ogden (Little River County). Traveling the north side of the Red River, they approached a province they recorded as Naguatex. Archaeological evidence and later historical documents define a dense population extending along both sides of the Red River near Fulton (Hempstead County) to Shreveport, Louisiana. The largest surviving Caddo mound in Arkansas (670′ long, 320′ wide, and 34′ high) and many smaller mounds are in that area.

The Naguatex caddi was powerful enough to direct three other caddis and many warriors in an attack on the Spaniards. Caddo bows and arrows, made of local bois d’arc wood, were renowned for their superiority. It was said that Caddo could easily send an arrow through a bison, but bows, arrows, and expert marksmanship could not equal muskets and soldiers on horses. The warriors did not stop the army but temporary halted it so their families could move to safety. Crossing the Red River, the army looped through Caddo Hasinai territory in northeast Texas before giving up on finding an overland route to Mexico. Finally, it retraced its trail through Arkansas to the Mississippi River and built boats that carried them to their destination.

The province named Naguatex in de Soto documents is the homeland of the historically dominant Cadohadacho (Kadohadacho). That name combines two Caddo words. The first syllable, kadu, has lost its exact meaning; itmay be a derivative of caddi. Hadacho means “keen” or “sharp,” in the sense of a pain. Caddo, an abbreviation of Cadohadacho, eventually was used to identify all Caddo people. Caddo people now speak of themselves as being Cadohadacho or Hasinai—“Our People.”

Little is known about what happened in Caddo communities during a 144-year period between the de Soto-Moscoso expedition and 1687, when a small group of Frenchmen passed through the Cadohadacho community on the Red River and the Cahinnio Caddo near Camden (Ouachita County). A journal written by Henri Joutel is the next documented account of Caddo people and places in Arkansas. His journal includes a detailed description of the ill-fated colony that René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle tried to establish on the gulf shore of Texas. It details the travels of survivors as they wandered through Caddo country on their way to French outposts, passage up the Mississippi to an outpost on the Illinois River, and an eventual return to France. With Caddo aid, the survivors reached the outpost now called Arkansas Post (Arkansas County).

By the time the Caddo met Joutel and his survivors, mound building had almost ceased, and smaller communities had begun to merge with larger ones. Joutel’s journal records incidents that confirm the strength of Caddo religious beliefs and gradual changes that affected their way of life. After one of Joutel’s party drowned and was buried in a field, the caddi’s wife carried a small basket of roasted ears of corn to the grave every morning. At the Cahinnio settlement, the Frenchmen were asked to participate in a ceremony that included singing by men and women accompanied by gourd rattles, and for the first time, the Frenchmen witnessed a calumet (ceremonial pipe) ritual performed by Caddo. That the Caddo did not yet have guns is shown by hunting incidents. Cahinnio guides killed bison with bow and arrow and, sighting a herd, insisted that it was the Frenchmen’s turn to make the kill. When a single shot from a musket dropped a bison, the Caddo hunter-guides were astounded by the hole and marveled at the shattered bone.

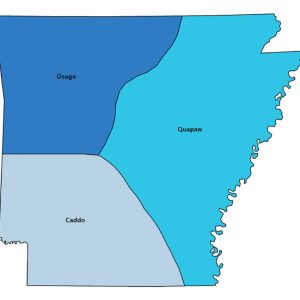

The brief meetings with Frenchmen described in Joutel’s journal were the beginning of increasing contact between Arkansas Caddo and eighteenth-century Europeans. France and Spain, rivals for territory in North America, vied for the allegiance of Caddo leaders, who not only kept peace and order in their communities but wielded influence over neighbors. Face-to-face contact with the Spanish was negligible, but the French, promoting trade, became allies. Raids on northern Caddo communities, primarily by the Osage, made guns vital. European fabrics, knives, needles, metal tools, and trinkets were useful. French traders came to live in Caddo communities, and dependence on their wares increased.

By 1790, weakened by European epidemics and raids by enemies—principally Osage—the Caddo who knew Arkansas as home abandoned their ancient territory and moved farther down the Red River, nearer French trade centers. Their old home remained their recognized hunting territory. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 included all of what is now Arkansas; three years later, when President Jefferson sent the Freeman-Custis expedition to explore the Red River, the explorers saw the ruins of Caddo villages and noted a large mound that their Caddo guides said was a place their forefathers worshiped.

The first American agent the Caddo dealt with, like the French and Spanish governors who preceded him, recognized and made use of the extraordinary influence and diplomacy of the grand caddi. But by 1818, Major Stephen H. Long, commander at Fort Smith (Sebastian County), reported that the Caddo who “inhabited a part of the country before the cession of Louisiana to the United States… pretended to claim all the country.” The next year, when Arkansas Territory was organized, surveyors began measuring lines running through Caddo country. The conclusive loss of Caddo homelands in Arkansas came in 1835, when their headmen were coerced to sign a treaty ceding all Caddo land in the nation, never again to live there as a group.

Caddo people endured a long journey from their ancient homelands to Caddo County, Oklahoma, where they now have their seat of government, five miles east of the town of Binger, where the Caddo Heritage Museum is located. Early in 2006, the official roll of the federally recognized Caddo Nation of Oklahoma listed 4,774 members, all lineal descendants of the ancient Caddo Nation. The majority live in Oklahoma; others, though living in other states, maintain close ties with the center of the modern Caddo Nation. Still, Caddo names remain on modern maps of Arkansas, and Caddo people remember and revere Arkansas as a place of their ancestors. As one twentieth-century Caddo grandmother wistfully said, “We once had all of Miller County.”

Today’s generation of Caddo frequently visit Arkansas, informally as tourists and formally as representatives responding to invitations to speak to audiences or to perform the traditional songs and dances that have been handed down from time beyond memory. Contemporary Caddo make such visits with mixed emotions: dismay that sacred ground has sometimes been disturbed by vandals, appreciation that professional research and study by Arkansas archaeologists and ethnologists contribute prehistoric evidence and historic documentation of the heritage that distinguishes them from all other people, and gratitude that the state of Arkansas has enacted laws for the protection and respect of sacred sites where the Old Ones lived and died.

For additional information:

Carter, Cecile Elkins. Caddo Indians: Where We Come From. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995.

Girard, Jeffrey S. The Caddos and Their Ancestors: Archaeology and the Native People of Northwest Louisiana. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2018.

Lee, Dayna Bowker. “A Social History of Caddoan Peoples: Cultural Adaptation and persistence in a Native American Community.” Ph.D. diss., University of Oklahoma, 1998.

McKinnon, Duncan P. The Battle Mound Landscape: Exploring Space, Place, and History of a Red River Caddo Community in Southwest Arkansas. Research Series 68. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 2017.

McKinnon, Duncan P., Jeffrey S. Girard, and Timothy K. Perttula, eds. Ancestral Caddo Ceramic Traditions. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2021.

Perttula, Timothy K. The Caddo Nation: Archaeological and Ethnohistoric Perspectives. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992.

Perttula, Timothhy K., and Chester P. Walker, eds. The Archaeology of the Caddo. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

Smith, Foster Todd. “On the Convergence of Empire: The Caddo Indian Confederacies, 1542–1835.” Ph.D. diss., Tulane University, 1989.

Swanton, John R. Source Material on the History and Ethnology of the Caddo Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

Trubitt, Mary Beth. “Burning and Burying Buildings: Exploring Variation in Caddo Architecture in Southwest Arkansas.” Southeastern Archeology 28 (Winter 2009): 233–247.

Trubitt, Mary Beth, with Lucretia S. Kelly. Two Caddo Mounds Sites in Arkansas. Research Series No. 70. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 2021.

Young, Gloria A., and Michael P. Hoffmann, eds. The Expedition of Hernando de Soto West of the Mississippi, 1541–1543: Proceedings of the de Soto Symposia, 1988 and 1990. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Cecile Elkins Carter

Caddo Nation of Oklahoma

Good information! My family settled around Montgomery Co., mainly around Mt. Ida. My grandfather told many stories, and always told us kids to stay off and away from the mounds. While we are all scattered around the country today, the old home country still has a hold on me. I love the history as told here.

I live in Caddo Valley, Arkansas, and work in Arkadelphia. I’ve been on a quest to find the true nature of this place I’ve been born from, this river and these hills that have fed and sheltered me. I knew I had to find the Old Ones. This article has jumped me miles ahead on my journey to find these people.

One of the best-written articles on the Caddo Nation I have read. The Microsoft Maps pre 1996 with high resolution will show you where the Nation built their homes along the Red River. I do believe one near Gin City shows a burned out compound where DeSoto may have wintered in the valley just southwest of the Nagutex tribe. The Teran MAP 1961, which is to depict the Hatcher Mound area, is actually at the LA/AR border on the Red River where I believe the great religious leader of the Nation lived quietly and the Nation never divulged his identity to DeSoto. When you look at the map it is identical to this location. This location is next to where the French built their trading post and the United States took over as an Indian Factory. When looking for the Indian houses you will see where the tree stumps that supported these round houses look like a pair of binoculars with a dot in the middle where the fire kept burning.