calsfoundation@cals.org

Civil Rights Movement (Twentieth Century)

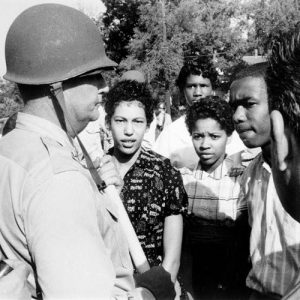

The 1957 desegregation crisis at Central High School in Little Rock (Pulaski County) is often viewed as the most significant development in the civil rights struggle in Arkansas. However, this event is just one part of a struggle for African-American freedom and equality that both predates and outlasts the twentieth century.

African Americans in Arkansas at the turn of the twentieth century were in an embattled state, as they were across the rest of the South. They were politically disfranchised and increasingly segregated in most areas of public life. In the Arkansas Delta, where the vast majority of Arkansas’s Black population was concentrated throughout the twentieth century, Black citizens were often bound to the land by exploitative peonage contracts with white landowners. Race-baiting political demagogues such as Governor Jeff Davis stirred up anti-Black sentiment with incendiary rhetoric: “We may have a lot of dead Negroes in Arkansas,” said Davis, in a campaign speech when he ran for re-election in 1904, “but we shall never have Negro equality….I would rather tear, screaming from her mother’s arms, my little daughter and bury her alive than to see her arm in arm with the best nigger on earth.” After being re-elected as governor (serving three terms in all), Davis was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1906.

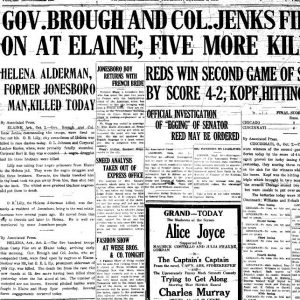

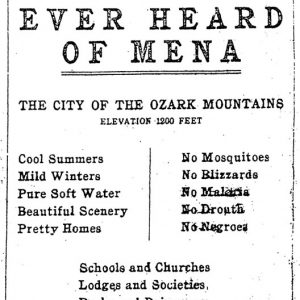

Extra-legal white violence and lynching reinforced legal measures to control the Black population. Periodic race riots occurred across the state from Hempstead County in southwest Arkansas in 1883, to Harrison (Boone County) in northwest Arkansas in 1905 and 1909, to Elaine (Phillips County) in the Arkansas Delta in 1919. According to statistics compiled by the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, which are almost certainly underestimated, 226 Blacks were lynched in Arkansas between 1882 and 1968, placing it seventh highest in the nation for the occurrence of such murders.

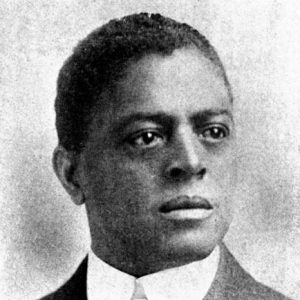

With little power or help to resist their situation, many Black citizens followed the lead of the foremost regional and national Black leader of the time, Booker T. Washington, in forming exclusively Black institutions, organizations, associations, and businesses to sustain the Black community. Nevertheless, protests did occur. In response to the Streetcar Segregation Act of 1903, Black citizens in Little Rock, Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), and Hot Springs (Garland County) launched a sustained but ultimately unsuccessful boycott. One of the people at the forefront of the civil rights struggle during this period was Black Little Rock lawyer Scipio Africanus Jones. His most notable case came when, employed by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), he successfully managed to win a custodial rather than a death sentence for six of the twelve Black prisoners convicted after the 1919 Elaine Massacre in Phillips County (the other six men were freed on appeal to the Arkansas Supreme Court). Despite the legal landmark case this produced for the NAACP, handed down by the U.S. Supreme Court in Moore v. Dempsey (1923), the leading national civil rights organization of the time found little support in the state. The first and largest branch in Arkansas formed in Little Rock in 1918 and remained largely inactive.

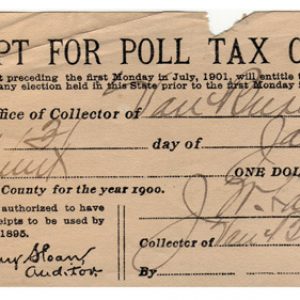

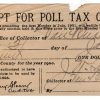

Jones also spearheaded the struggle for Black political representation in an increasingly “lily-white” Arkansas Republican Party. In 1928, he gained election as a delegate to the Republican National Convention, but this represented only a limited and begrudging compromise by whites. Blacks would not be an important factor in the party again (as they had been during Reconstruction and its immediate aftermath)until the late 1960s. The decline of Black political influence in the Arkansas Republican Party by the late 1920s made little difference to the Black population’s overall influence in state politics. By that time, the Arkansas Democratic Party was entrenched as the main political force in the state. Blacks could vote at general elections after the payment of a one-dollar poll tax, yet even this price was beyond the means of many, and the tax did not necessarily guarantee that Black votes would be counted by whites at the ballot box. In any case, it was the Democratic primaries where real power lay, since whoever won the party nomination inevitably won the general election, which was often uncontested. It was the Arkansas Democratic Party’s white primary system that effectively excluded Blacks from local and state politics.

The lynching of John Carter, whose mutilated body was paraded around the streets of Little Rock by a mob of over 1,000 in 1927, underscored the need for Black political empowerment. A challenge to Jones’s political leadership came from Black Little Rock physician Dr. John Marshall Robinson in 1928, when he founded the Arkansas Negro Democratic Organization (ANDA) and sued in the courts for Black citizens’ right to vote in state Democratic Party primaries. (Another prominent Black Little Rock figure, John Hamilton McConico, was ANDA secretary.) After Robinson won a temporary victory in the local courts, the ruling was overturned. It was unsuccessfully appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court as Robinson v. Holman (1930).

The 1930s marked a watershed in the civil rights struggle that saw segregation begin to weaken as foundations were laid for the later civil rights movement. Although ultimately ambiguous, the New Deal did give hope to Blacks of federal intervention on their behalf. With the mechanization and collectivization of agriculture in the Arkansas Delta, it also paved the way for the urbanization of the Black population. Larger Black communities in villages, towns, and cities proved an essential building block for later Black mobilization. In 1934, the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU) was founded by Blacks and whites in Poinsett County, a rare and short-lived example of biracial protest against sharecropping and tenant farming. World War II acted as a further catalyst for change. It witnessed an upsurge in Black activism, reflected in a tenfold growth in national NAACP membership. Many of its half a million members by the end of the war belonged to burgeoning Southern branches.

Black Pine Bluff lawyer William Harold Flowers played a crucial role in establishing the NAACP as a force in Arkansas. When the NAACP initially rebuffed his offers of help in setting up branches, Flowers launched his own Committee on Negro Organizations (CNO) to mobilize voter registration drives in the state. Flowers and the CNO were convinced that if Blacks began to purchase poll tax receipts and to cast their votes in general elections, it would prove a vital first step in raising Black political consciousness to challenge the white Democratic primaries. “Drive to Increase Race Votes Is Successful” headlined the Arkansas State Press, the Little Rock–based Black newspaper, at the end of the CNO’s campaign. The paper was owned by husband and wife team L. C. Bates and Daisy Bates, who were good friends of Flowers.

The increase in Black activism was demonstrated by developments in Little Rock. In 1942, a campaign by the Arkansas State Press led to the appointment of the first eight Black police officers in Little Rock. This followed Black outrage at the killing of Black Sergeant Thomas B. Foster from the nearby Camp Robinson army base by city policeman Abner J. Hay on downtown West 9th Street. In 1942, Sue Cowan Williams acted as plaintiff on behalf of the Little Rock Classroom Teachers’ Association in an NAACP-backed lawsuit to equalize Black and white teachers’ salaries. The case was won on appeal in 1945.

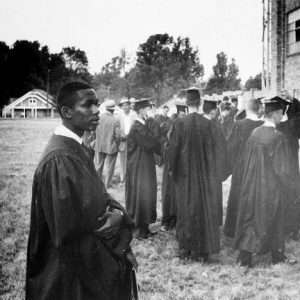

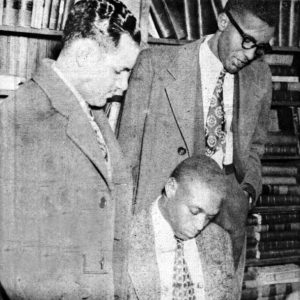

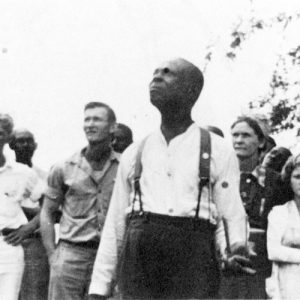

The success of the teachers’ salary equalization suit brought renewed interest from the NAACP. In 1945, it set up an Arkansas State Conference of NAACP branches (ASC). Reflecting the caution of the national organization, it appointed the older and more conservative Reverend Marcus Taylor in Little Rock as president while making the younger Flowers chief organizer of branches. Flowers built upon and extended the organizational network created by the CNO. Conflict between the two men soon arose. In 1948, Flowers and his supporters ousted Taylor as president and installed their own man. Just a year later, however, Flowers was forced to resign as president amid much controversy after allegations of financial improprieties. He nevertheless remained an important figure in the state. In February 1948, he and his Black Pine Bluff attorney protégé Wiley Branton, along with Black Pine Bluff photographer Geleve Grice, accompanied Silas Hunt on his successful enrollment in the University of Arkansas (UA) School of Law in Fayetteville (Washington County). Hunt’s enrollment was the first time a Black student had attended a university with whites in the South since Reconstruction. Although Hunt was forced to withdraw due to illness, other Black students soon followed in his footsteps, including, in 1951, Jackie Shropshire, the first Black UA graduate; Wiley Branton; Christopher Mercer; George Haley; and George Howard. Edith Irby desegregated the university medical school in Little Rock (now the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences) in 1948, graduating in 1952.

Another indication of Flowers’s impact was the rising number of registered Black voters. In 1940, the number stood at only 4,000, but, by 1947, it had increased to 47,000. The battle to end the white primaries came in 1950 when the Little Rock NAACP branch filed suit to win Black Little Rock minister the Reverend J. H. Gatlin a place on the Democratic Party ballot. The Democratic State Convention changed its rules to allow full Black participation later that year.

The struggle over NAACP leadership in the state was resolved in 1952 with the election of Daisy Bates as president. This came at a crucial time shortly after the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas school desegregation ruling. Several school boards in Arkansas complied almost immediately, including those at Charleston (Franklin County), Fayetteville (Washington County), and Bentonville (Benton County). This was largely because of the small number of Black students involved. (Despite this progress in schools, northwest Arkansas remained home to a number of “sundown towns,” places in which African Americans were forbidden to live or be seen after dark.) Hoxie (Lawrence County), in northeast Arkansas, encountered significant opposition to desegregation in 1955 until the courts stepped in to stop the interference of segregationists. Little Rock also appeared to make progress. However, when the Little Rock School Board began to modify its initial desegregation plans, the NAACP filed suit in Aaron v. Cooper (1956). The suit was unsuccessful in its aim of winning admission of thirty-three Black students to white schools, but the courts did assert that the school board should carry out the implementation of desegregation as planned in September 1957.

The events of the 1957 Little Rock desegregation crisis and the stories of the Little Rock Nine students who integrated Central High School have been extensively documented, as has the role of Governor Orval Faubus and the story of the Lost Year from 1958 to 1959, when Little Rock voters voted to keep their schools closed rather than to integrate them. Equally prominent are the stories of the landmark Cooper v. Aaron (1958) U.S. Supreme Court ruling, as well as the campaign to reopen the schools waged between the Women’s Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools (WEC), Stop This Outrageous Purge (STOP), and the Committee to Retain Our Segregated Schools (CROSS). Little Rock schools reopened in August 1959 on a token integrated basis.

As the struggle for school desegregation continued, the focus of civil rights activism expanded in the state, as it did across the South and the nation in the 1960s. This required new Black leadership and organizations. The NAACP came under attack during the school crisis, and its membership fell dramatically. Attorney General Bruce Bennett composed bills to prevent the organization from providing legal counsel and funding lawsuits, to force it to make public NAACP membership details, and to prevent state employment of NAACP members. The Arkansas State Press went out of business in October 1959 due to a boycott by white advertisers who were intimidated by segregationists. Daisy Bates left Little Rock for New York City to write her memoirs, leaving a vacuum in leadership for the NAACP and Black activism in the city and the state.

Initial attempts to revive Black activism in Little Rock came from Philander Smith College students who, following the outbreak of a southern-wide sit-in movement and the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in early 1960, formed their own self-styled “Arsnick.” However, their attempts to stage sit-ins in downtown Little Rock met with hefty fines and harsh jail sentences, bringing those demonstrations to a premature and unsuccessful end. Likewise, Little Rock’s brief encounter with the Freedom Rides in 1961, which formed part of the extended Freedom Rides inspired by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and SNCC, failed to bring any change in city desegregation policy. But these developments did ultimately inspire the formation of the Council on Community Affairs (COCA) by a young group of Black Little Rock medical professionals, Dr. William H. Townsend, Dr. Maurice A. Jackson, Dr. Garman P. Freeman, and Dr. Evangeline Upshur. Connecting these people with earlier activism, the four had previously shared a practice with Dr. John Marshall Robinson on West 9th Street. COCA was an outgrowth of the interracial Arkansas Council on Human Relations (ACHR), founded in the state in 1954, and an affiliate of the Atlanta-based Southern Regional Council (SRC). ACHR associate director Ozell Sutton also played an important role in COCA.

COCA and the ACHR were instrumental in inviting SNCC into Arkansas in 1962. In October, white SNCC worker Bill Hansen was sent from the central office in Atlanta to help mobilize Black students at Philander Smith. Renewed sit-ins forced white businessmen, headed by James Penick, president of Worthen Bank and Trust Company, to form a Downtown Negotiating Committee to end segregation in Little Rock. This was done by a phased plan of desegregation in 1963. Building on its success in Little Rock, SNCC, with the help of other volunteers, moved to other parts of the state. It was principally based in Pine Bluff, Helena (Phillips County), Forrest City (St. Francis County), and Gould (Lincoln County). Civil rights activism began to spread across the state. As SNCC moved deeper into the Arkansas Delta, which had larger Black populations and greater racial tensions, white opposition became fiercer.

One of the most important developments in the 1960s was in voting rights. In 1964, the passage of the Twenty-fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution outlawed the use of the poll tax in federal elections. In 1965, Arkansas abolished the poll tax as a requirement for voting and introduced a permanent personal voter registration system. The 1965 Voting Rights Act further bolstered Black voting rights by, among other measures, removing literacy tests as a voting qualification. The earlier 1964 Civil Rights Act had outlawed unequal application of voter registration requirements. Winthrop Rockefeller successfully won election as the first Arkansas Republican governor since Reconstruction in 1966, his campaign having actively courted Black voters. Upon his reelection in 1968, he won eighty-eight percent of the Black vote. This was assisted by the Arkansas Voter Education Project (AVP), run under the umbrella of the region-wide SRC-sponsored Voter Education Project (VEP). The VEP director was Arkansan Wiley Branton. A number of local civil rights groups, including COCA, SNCC, and the NAACP contributed to the campaign.

The late 1960s saw increasing radicalization of the civil rights movement and the emergence of Black power. SNCC decided to remove white members from the organization in 1967, soon leading to its collapse in Arkansas. The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968 led to a shift in emphasis from peaceful demonstrations to more militant forms of activism and even violence. In the wake of King’s death, fires broke out in Black areas at Hot Springs and North Little Rock (Pulaski County), while conflict between demonstrators and police in Pine Bluff led to the shooting and wounding of four Black people. In August 1969, eighty Black citizens marched on the City Hall in Benton (Saline County) after the shooting of a Black youth by a white restaurant owner. In August 1970, the white owner of a grocery store in Blytheville (Mississippi County) shot and killed a Black picketer, leading to major unrest there. In September 1971, a shootout occurred between local Blacks and members of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in Parkin (Cross County). In the heartland of the Arkansas Delta, in places like Forrest City (St. Francis County), Marianna (Lee County), and Earle (Crittenden County), demonstrations, shootings, and racial violence became part of the fabric of everyday life. In Little Rock, Bobby Brown, the younger brother of Minnijean Brown, one of the nine students to integrate Central High School in 1957, headed the city’s Black power group Black United Youth (BUY). Brown described BUY as “an eyeball to eyeball organization” dedicated to “direct confrontation with white people for making changes” in areas such as schools, jobs, and housing.

By the early 1970s, as Black rebellion was subdued, attention began to shift back to implementing the gains of the civil rights movement and in particular the task of building political power in the state. In 1972, Arkansas boasted ninety-nine Black elected officials, the second-highest number of any Southern state. A former NAACP president, North Little Rock dentist Dr. Jerry Jewell, became the first Black member of the Arkansas Senate. COCA’s Dr. William Townsend became one of three Black politicians elected to the Arkansas House of Representatives. Little Rock lawyer Perlesta A. Hollingsworth became the second Black member of the city directors’ board in Little Rock, following Charles Bussey, who was elected in 1968. Throughout the state, African Americans won elective offices as aldermen, mayors, justices of the peace, school board members, city councilors, city recorders, and city clerks. These gains further stimulated Black voter registration. By 1976, ninety-four percent of black Arkansans of voting age were registered, the highest percentage of any state in the South.

The task of translating Black political power into day-to-day gains is ongoing. Black Arkansans collectively remain comparably worse off than whites in almost every category. The ambiguity of gains made by civil rights struggles in the twentieth century is evident. Despite increased voter registration, Arkansas has yet to return a Black congressperson to Washington DC. White population flight out of the Arkansas Delta, and out of built-up areas in towns and cities to sprawling suburbs, has led to increased geographical separation of the races. In Little Rock, millions of dollars of federal funds have been used to create a more geographically racially divided city. During the 1960s and 1970s, 41,000 whites moved from east to west of the city, while 17,000 Blacks moved—or were moved—in the opposite direction. This figure represented over forty percent of the city’s total population.

The impact of the increasing geographical separation on the racial makeup of schools has been dramatic. For example, as the Little Rock School District sought to implement different plans for desegregation from the 1960s onward, some voluntary, some by federal compulsion, the geographical divide between the races continually undercut their effectiveness. When busing was introduced in the early 1970s to counteract the effects of racially defined residential patterns, whites built private schools in the suburbs or fled the county altogether. In 1971, insurance and real estate man William F. Rector announced the construction of the private Pulaski Academy in the western suburbs of the city for those, he said, who “don’t like busing.” In 2003, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reported a tipping point had been reached and that Little Rock had become “a city of mostly black public schools and mostly white private schools.” In February 2007, the courts declared the Little Rock School District unitary. From being a twenty-five-percent Black minority district in 1957, it had become a twenty-four-percent white minority district in 2007. In effect, there were no white students left to integrate.

Although Black Arkansans were undoubtedly better off at the turn of the twenty-first century than they were at the turn of the twentieth century, the struggle for civil rights, equality, and justice continues.

For additional information:

Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Cortner, Richard C. A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases. Middletown: University of Connecticut Press, 1988.

Dillard, Tom. “‘To the Back of the Elephant’: Racial Conflict in the Arkansas Republican Party.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 33 (Spring 1974): 3–15.

Gatewood, Willard B. Aristocrats of Color: The Black Elite, 1880–1920. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990.

Gipson, Maurice D. “A Natural Fit for the Natural State: The Emergence of Black Power Organizations in Arkansas from 1968–1975.” PhD diss., University of Mississippi, 2021.

Gordon, Fon Louise. Caste and Class: The Black Experience in Arkansas, 1880–1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995.

Graves, John William. Town and Country: Race Relations in an Urban-Rural Context, Arkansas, 1865–1905. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Jones-Branch, Cherisse. Better Living by Their Own Bootstraps: Black Women’s Activism in Rural Arkansas, 1914–1965. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2021.

Key, Barclay. “On the Periphery of the Civil Rights Movement: Race and Religion at Harding College, 1945–1969.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 68 (Autumn 2009): 283–311.

Kilpatrick, Judith. There When We Needed Him: Wiley Austin Branton, Civil Rights Warrior. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

Kirk, John A. “Battle Cry of Freedom: Little Rock, Arkansas, and the Freedom Rides at Fifty.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 42 (August 2011): 76–103.

———. Beyond Little Rock: The Origins and Legacies of the Central High Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

———. “Not Quite Black and White: School Desegregation in Arkansas, 1954–1966.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (August 2011): 225–257.

———. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Land of (Unequal) Opportunity: Documenting the Civil Rights Struggle in Arkansas. Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries. https://digitalcollections.uark.edu/digital/collection/Civilrights#:~:text=%22Land%20of%20(Unequal)%20Opportunity,civil%20rights%20in%20the%20state (accessed April 20, 2022).

Lewis, Catherine M., and J. Richard Lewis, eds. Race, Politics and Memory: A Documentary History of the Little Rock School Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

Lewis, Todd E. “Race Relations in Arkansas.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 1995.

“The Little Rock Crisis: A Fiftieth Anniversary Retrospective.” Special issue, Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Summer 2007).

McGee, Holly Y. “‘It Was the Wrong Time, and They Just Weren’t Ready’: Direct-Action Protest in Pine Bluff, 1963.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Spring 2007): 18–42.

Oral Histories: Delta Project. UCA Archives. University of Central Arkansas, Conway, Arkansas. https://uca.edu/archives/delta-project-history/ (accessed April 18, 2025).

Pierce, Michael. “Historians of the Central High Crisis and Little Rock’s Working-Class Whites: A Review Essay.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Winter 2011): 462–483.

———. “Odell Smith, Teamsters Local 878, and Civil Rights Unionism in Little Rock, 1943–1965.” Journal of Southern History 84 (November 2018): 925–958.

Riva, Sarah. “The Shallow End of the Deep South: Civil Rights Activism in Arkansas, 1865–1970.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2020. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3797/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Smith, C. Calvin. War and Wartime Changes: The Transformation of Arkansas, 1940–1945. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

Stockley, Grif. Daisy Bates: Civil Rights Crusader from Arkansas. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2005.

———. Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2008.

Stockley, Grif, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919. Rev. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Whayne, Jeannie H. “Black Women in the Civil Rights Movement in Arkansas.” In Southern Black Women in the Modern Civil Rights Era, edited by Bruce A. Glasrud and Merline Pitre. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2013.

———. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor and Federal Favor in the Twentieth-Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996.

Williams, Johnny E. African-American Religion and the Civil Rights Movement in Arkansas. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2003.

Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth. American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

John A. Kirk

Royal Holloway, University of London

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.