calsfoundation@cals.org

Freedom Rides

The Freedom Rides were a tactic employed by civil rights demonstrators in 1961 to place pressure on the federal government and local leaders to end segregation in interstate transportation facilities. Ultimately, the Freedom Rides in Little Rock (Pulaski County) led the local African-American and white communities to address the lingering issue of segregation in the city.

In 1947, the national civil rights organization the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) held its Journey of Reconciliation to test integrated interstate transportation on buses ordered by the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1946 Morgan v. Virginia decision. The journey involved an interracial team of bus passengers traveling through upper South states to make sure the law was being implemented. Their journey met with mixed results. In some places, they were allowed to ride interstate buses, while in others they were arrested.

In 1960, the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Boynton v. Virginia extended its Morgan ruling on interstate buses to interstate bus terminal facilities. CORE this time tested the ruling with Freedom Rides. In May 1961, two sets of interracial Freedom Riders were attacked on their journey through Alabama. The national headlines the attacks drew forced federal intervention by the John F. Kennedy administration to assist the riders to reach their destination of Jackson, Mississippi.

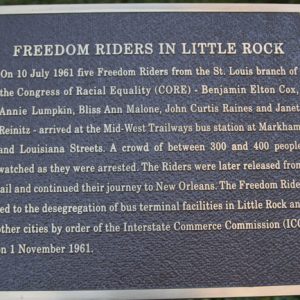

A Freedom Ride Coordinating Committee (FRCC) was subsequently formed to coordinate further rides across the South in the summer of 1961. As part of this campaign, Freedom Riders arrived in Little Rock on the evening of July 10, 1961, from the CORE branch of St. Louis, Missouri. The riders planned a journey from St. Louis to Little Rock, then on to Shreveport, Baton Rouge, and New Orleans, Louisiana. The riders were led by thirty-year-old Rev. Benjamin Elton Cox, an African-American native of Whiteville, Tennessee, who served as a minister at Pilgrim Congregational Church in High Point, North Carolina, and as a CORE field secretary. Cox was a veteran of the initial Freedom Rides. The other riders were twenty-three-year-old Bliss Anne Malone, an African-American public school teacher from St. Louis; eighteen-year-old Annie Lumpkin, an African-American student from St. Louis; twenty-seven-year-old John Curtis Raines, a white pastor from Setauket Methodist Church in Long Island, New York, and a former Fulbright scholar; and twenty-three-year-old Janet Reinitz, a white artist and homemaker from New York City.

When the riders’ bus pulled into the Midwest Trailways station at Markham and Louisiana streets, a crowd of between 300 and 400 whites were there to meet them. The arrangements inside the bus terminal were complicated. The Boynton ruling had ordered desegregation of interstate terminal facilities. Obeying the letter if not the spirit of the law, the bus terminal had an integrated “Inter-State and Colored Intra-State Waiting Room” for white interstate and African-American intrastate passengers and a segregated “White Intra-State Waiting Room” for white intrastate passengers. There was no lunch counter, just a snack bar that opened onto both waiting rooms. The Freedom Riders headed for the white intrastate waiting room.

Little Rock police chief Robert E. (Bob) Glasscock asked the riders to leave the bus terminal. They refused. Glasscock arrested them for a breach of the peace under Arkansas Act 226 passed by the 1959 Arkansas General Assembly. They were taken to the Little Rock City Jail. The following day, two local Little Rock African-American attorneys handling their case, Thaddeus D. Williams and Edward V. Trimble, asked for a delay to prepare for trial. Little Rock Municipal Court judge Quinn Glover granted their request.

Meanwhile, there was much debate in the white community about the Freedom Ride. The Arkansas Gazette did not approve of the ride but denounced police handling of the matter. It was unhappy about headlines of racial strife in a city still recovering from the desegregation of Central High School. The Arkansas Democrat laid all the blame on the Freedom Riders. Leading merchants, bankers, and business leaders in the city formed the ad hoc Civic Progress Association (CPA). They diplomatically backed the actions of the police while expressing “regret that it became necessary to take the riders into custody.”

On Wednesday, July 12, the riders appeared in court. Judge Glover found them guilty and gave them a $500 fine and a six-month prison sentence. However, Glover offered to release them if they agreed to “leave the state of Arkansas and proceed to their respective homes.” They agreed after consultation with their lawyers and the St. Louis CORE branch. However, later that day when the riders discovered that Glover meant for them literally to return home rather than just to leave Arkansas, they returned to jail.

On Thursday, July 13, under pressure to get the city out of the headlines, Glover admitted he could not legally compel the riders to return home. Instead, he said they could have their fines and sentences revoked if they agreed to leave the state peacefully and not to test any more facilities there. The riders agreed. The same afternoon, they left Little Rock to continue their journey.

The following week, another group of five Freedom Riders arrived. They had already successfully tested bus terminal facilities in Virginia and Tennessee. They had run into difficulties in Stuttgart (Arkansas County), where the workers at the bus terminal had refused them service and the driver of their Greyhound bus had tried to leave without them. Later that day, they arrived at Little Rock’s Greyhound Union bus station at West 6th Street and Broadway. They tested terminal facilities without any trouble, an indication that the city had learned its lesson from the week before.

Freedom Rides like the ones in Little Rock had a successful cumulative impact in placing pressure on the federal government to uphold the Boynton ruling. The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) issued guidelines to forbid segregation in bus terminals that came into effect November 1, 1961. Little Rock implemented the guidelines peacefully, and segregation in bus terminal facilities came to an end in the city.

There was bizarre coda to the Freedom Rides in Little Rock. In 1962, Amis Guthridge of the Capital Citizens’ Council (CCC) embraced the idea of “Reverse Freedom Rides” to send African-American families north. The CCC paid the one-way fares of more Reverse Freedom Riders than any other Citizens’ Council branch in the nation, approximately 200 total, sending them to Hyannis, Massachusetts, the summer home of the Kennedy family. The New York Times described the Reverse Freedom Rides as “a cheap trafficking in human misery.” As the Citizens’ Councils ran out of money for fares, the Reverse Freedom Rides ground to a halt in late summer 1962.

A new local African-American organization, the Council on Community Affairs (COCA), was founded on the same day that the second group of Freedom Riders left Little Rock. These local leaders, together with the help of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), placed sufficient pressure on local white business leaders to end segregation in all of Little Rock’s downtown facilities by 1963.

For additional information:

Arsenault, Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Barnes, Catherine. Journey from Jim Crow: The Desegregation of Southern Transit. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983.

Catsam, Derek Charles. Freedom’s Main Line: The Journey of Reconciliation and the Freedom Rides. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2009.

Kirk, John A. “Battle Cry of Freedom: Little Rock, Arkansas, and the Freedom Rides at Fifty.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 42 (August 2011): 76–103.

———. “A Forgotten Freedom Summer.” Arkansas Times. July 6, 2011, pp. 10–15. Online at http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/a-forgotten-freedom-summer/Content?oid=1852445 (accessed February 2, 2022).

———. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Niven, David. The Politics of Injustice: The Kennedys, the Freedom Rides, and the Electoral Consequences of a Moral Compromise. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2003.

Raines, John Curtis. “Get on the Bus: Freedom Riders’ Work Remains Unfinished.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. July 3, 2011, pp. 1H, 6H.

Webb, Clive. “‘A Cheap Trafficking in Human Misery’: The Reverse Freedom Rides of 1962.” Journal of American Studies 38 (2004): 249–271.

Wofford, Harris. Of Kennedys and Kings: Making Sense of the Sixties. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1980.

Zinn, Howard. SNCC: The New Abolitionists. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1965.

John A. Kirk

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Civil Rights Movement (Twentieth Century)

Civil Rights Movement (Twentieth Century) World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Cox Marker

Cox Marker  Freedom Rides

Freedom Rides  Freedom Rides

Freedom Rides  Freedom Riders Plaque

Freedom Riders Plaque  Lumpkin Marker

Lumpkin Marker  Annie Lumpkin

Annie Lumpkin  Malone Marker

Malone Marker  Bliss Anne Malone

Bliss Anne Malone  Arrest of Bliss Anne Malone

Arrest of Bliss Anne Malone  Raines Marker

Raines Marker  Reinitz Marker

Reinitz Marker

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.