ACORN Action

ACORN Action

Entry Category: Poverty

ACORN Action

ACORN Action

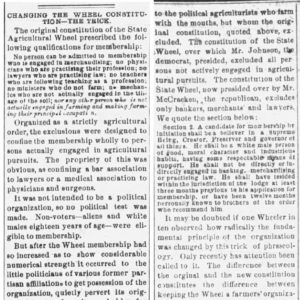

Agricultural Wheel Article

Agricultural Wheel Article

Freda Hogan Ameringer

Freda Hogan Ameringer

Ameringer, Freda Hogan

Arkansas River Valley Area Council (ARVAC)

Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN)

aka: ACORN

Becker, Jerome Bill

Bogus Cure

Bogus Cure

Brothers of Freedom

Ida Callery

Ida Callery

Callery, Ida Hayman

Central Arkansas Development Council

Coal Hill Convict Lease Investigation (1888)

Community Event

Community Event

Cotton Pickers

Cotton Pickers

Crossett Strike of 1940

Decatur Strike of 1951

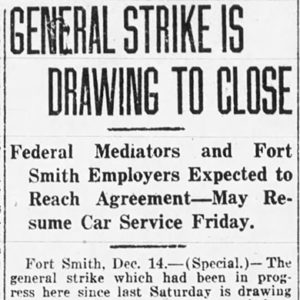

Fort Smith Strike Article

Fort Smith Strike Article

Fort Smith Telephone Operators Strike of 1917

Garden Party

Garden Party

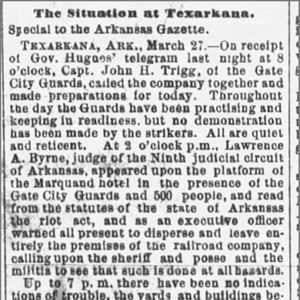

Great Southwestern Strike

Great Southwestern Strike Article

Great Southwestern Strike Article

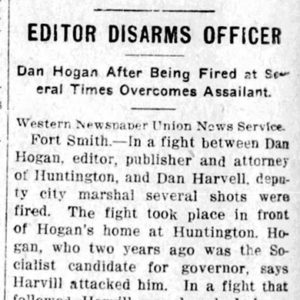

Dan Hogan Article

Dan Hogan Article

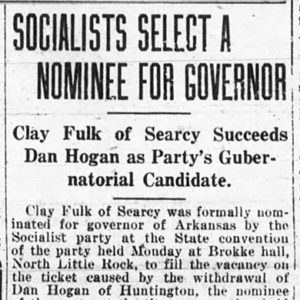

Dan Hogan Withdrawal

Dan Hogan Withdrawal

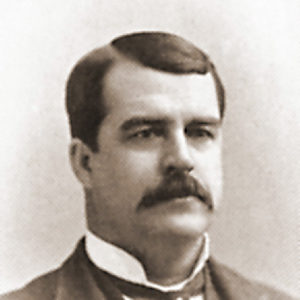

Hogan, Dan

Homelessness

Jeffords, Edd

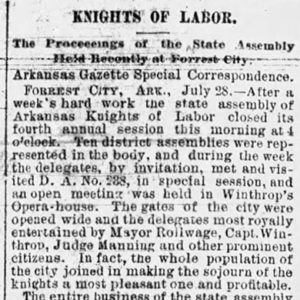

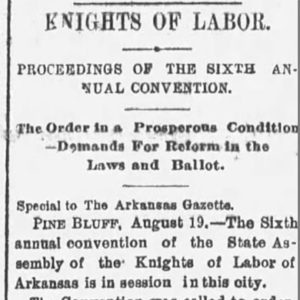

Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor Story

Knights of Labor Story

Knights of Labor Story

Knights of Labor Story

Landlord-Tenant Laws

Langley and Clayton Campaign

Langley and Clayton Campaign

Langley, Isom P.

Lightfoot, Claude M.

Lucie’s Place

Charles W. Macune

Charles W. Macune

McCracken Article

McCracken Article

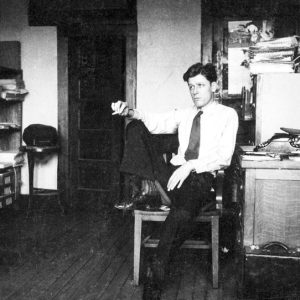

Harry Mitchell

Harry Mitchell

Mitchell, Harry Leland

National Farmers’ Alliance and Industrial Union of America

aka: Southern Farmers' Alliance

aka: Farmers' Alliance

aka: Arkansas State Farmers’ Alliance

National Grange of the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry

aka: The Grange

aka: Arkansas State Grange

aka: Patrons of Husbandry

Noble, Marion Monden

Operators Strike Article

Operators Strike Article

Ozark Institute [Organization]

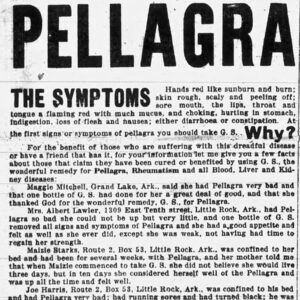

Pellagra

Pellagra Investigation

Pellagra Investigation

Pellagra Treatment

Pellagra Treatment