calsfoundation@cals.org

Isom P. Langley (1851–1930)

During the 1880s and early 1890s, Isom P. Langley was a leading figure in the farmer and labor movements in Arkansas. Active in organizations such as the Agricultural Wheel, which was founded in Des Arc (Prairie County) in 1882, and the Knights of Labor, he ran for the U.S. Congress twice. In 1891, he left Arkansas for Missouri, where he spent the second half of his life and served in the state legislature.

Born in Clark County, Arkansas, on September 2, 1851, to Samuel S. Langley and Mary J. Browning Langley, Isom Langley grew up on a farm and was educated in county schools. In 1868, he earned a license to preach, and the following year he became an ordained Baptist minister. In 1870, he married Martha A. Freeman; they had five children. While preaching, first in Arkadelphia (Clark County) and later in Hot Springs (Garland County) and Little Rock (Pulaski County), he began to study law. Admitted to the state bar in 1875, he practiced law in Arkadelphia and Hot Springs until 1885. At the same time, he became active in the newspaper business. In 1880, he formed a partnership with J. W. Miller and J. N. Miller and became the editor of the Arkadelphia Signal, a Democratic newspaper. Two years later, as Langley became a supporter of Arkansas’s nascent third-party movement, that newspaper became the Arkadelphia Clipper, a Greenback-Labor Party organ. Langley left that enterprise in 1883 and moved to Hot Springs, where he founded and edited the Hot Springs News.

In Hot Springs, Langley became more active in the labor and farmer movements. In 1885, he joined Hot Springs Assembly 2419 of the Knights of Labor, which three years earlier had become the first Arkansas lodge of that national organization. In 1886, he joined the Agricultural Wheel and became the chaplain of the Arkansas state chapter. He also became the editor of newspapers for both the Knights of Labor (Industrial Liberator) and the Agricultural Wheel (National Wheel Enterprise), each based in Little Rock.

In 1886, Langley ran for Congress in the state’s Fourth District, which included Pulaski County, as the sole challenger to Democratic incumbent John H. Rogers. The Knights of Labor had participated in two strikes in the district that year: the Great Southwestern Railroad Strike and the Tate Plantation Strike just south of Little Rock. Langley tried to cast his appeal as widely as possible, describing himself a “Democrat-Greenbacker-Republican-Wheeler-Knight of Labor-farmer-preacher-lawyer-editor.” Reports indicated that he was nominated by “a labor convention” or “by the Wheelers and Knights of Labor.” He received only thirty-eight percent of the vote in the district, but he did well in some areas where the Knights of Labor and the Agricultural Wheel were strong; he won fifty-six percent of the vote in Pulaski County.

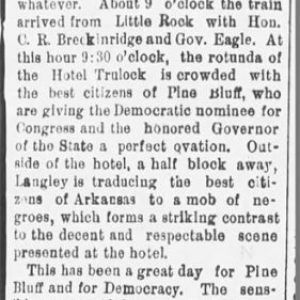

By 1888, third-party advocates in Arkansas came together in the Union Labor Party, which supported the anti-monopolistic reform programs of the Knights and the Wheel while also drawing considerable support from the state’s flagging Republican Party. In a state campaign that was marred by fraud and violence, Langley lost his bid for secretary of state as the Union Labor candidate. Two years later, he ran again for Congress, this time in the Second District of central Arkansas. In 1888, Democrat Clifton Breckenridge had been declared the winner in this district initially, but the U.S. House of Representatives overturned this result after an investigation that declared the Wheel-supported Republican candidate John M. Clayton to have been the winner. After Clayton was assassinated in 1889 while gathering evidence for his case, the seat was left vacant. Thus, in November 1890, two elections were held simultaneously in the Second District: one to fill the seat for the remainder of the Fifty-First Congress and another for the Fifty-Second Congress. National newspapers initially suggested that Langley had won, but amidst the undemocratic shenanigans that typified Arkansas elections in that era, Breckenridge was ultimately declared the winner of both elections.

Rather than contest the election results as Clayton had done, Langley left Arkansas in early 1891 to become the pastor of a Baptist church in Poplar Bluff, Missouri. He went on to serve one term (1919–1921) as a Missouri state legislator from Laclede County and as the chaplain at a prison in Jefferson City, Missouri, from 1921 until 1928. Langley died in Jefferson City on July 13, 1930. He is buried in that city’s Riverview Cemetery.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Eastern Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Company, 1890.

Elkins, F. Clark. “State Politics and the Agricultural Wheel.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 38 (Autumn 1979): 248–258.

Hild, Matthew. Arkansas’s Gilded Age: The Rise, Decline, and Legacy of Populism and Working-Class Protest. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2018.

———. “Labor, Third-Party Politics, and New South Democracy in Arkansas, 1884–1896.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 63 (Spring 2004): 24–43.

Paisley, Clifton. “The Political Wheelers and Arkansas’s Election of 1888.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 25 (Spring 1966): 3–21.

Wheeler, John M. “The People’s Party in Arkansas, 1891–1896.” PhD diss., Tulane University, 1975.

Matthew Hild

Georgia Institute of Technology

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Politics and Government

Politics and Government Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Langley and Clayton Campaign

Langley and Clayton Campaign

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.