calsfoundation@cals.org

Pellagra

Pellagra is a form of malnutrition caused by a severe deficiency of niacin (also known as nicotinic acid or vitamin B3) in the diet. The disease affected thousands of Arkansans and other Southerners in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

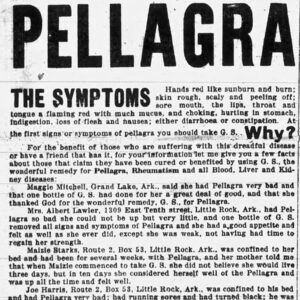

Symptoms of pellagra can include lack of energy, outbreaks of red splotches on the skin, diarrhea, and—in extreme cases—depression, dementia, and even death. Pellagra is not contagious, and the condition can be reversed. The lethargic appearance of pellagra victims was also a symptom of two other diseases widely found in the South at the time, hookworm and malaria. These three contributed to the false stereotype of Southerners at this time as lazy.

Pellagra was first recognized as a disease in 1762 in Europe. It was first reported in the United States in Alabama in 1902, but some studies suggest that it most likely existed in remote areas before that time. Because of the remote locations of many victims and poor recordkeeping at the time, the number of residents suffering from pellagra has never been clear, though several historical studies suggest that perhaps tens of thousands across the South suffered from the condition at one time or another. The intense poverty and lack of access to affordable medical care allowed the ailment to continue unabated.

The preparation of corn (or maize) among Native American groups included a process known as nixtamilization, whereby the corn was soaked and cooked in limewater or another alkaline solution, washed, and then hulled. This not only made it easier to grind, but it also increased the nutritional value by making the niacin more available for absorption in the body. European settlers in the United States adopted this method of food preparation, but Italians who imported corn from the U.S. in the 1800s were unaware of this, and consequently Italian peasants suffered an outbreak of pellagra.

Pellagra appeared in the American South on a large scale in the early twentieth century due largely to the institutionalized poverty of the sharecropping system. Plantation owners worked to prevent sharecroppers from farming anything other than cotton, even when cotton was unprofitable, in order to make them dependent upon the company store, where prices were often marked up significantly, and keep them in perpetual debt. In the early twentieth century, new milling technology allowed Midwestern corn mills to grind corn for shipping with less risk of it going bad by removing the germ, which is also the part of the seed that contains niacin. The availability of cheap and easily prepared rations almost immediately led to outbreaks of pellagra across the South.

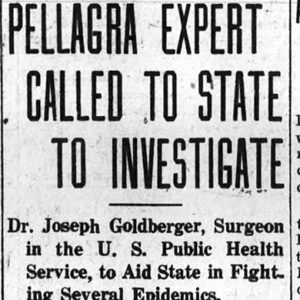

Dr. Joseph Goldberger of the United States Public Health Service conducted the first field studies of pellagra in the United States starting in 1914. Goldberger conducted an experiment with himself and ten other volunteers at the Rankin farm of the Mississippi State Penitentiary in 1915. Eating a diet common to Southern poor (salt meat, molasses, and corn meal), six of the eleven eventually developed pellagra, while none of the inmates, used as a control group for the experiment, developed the condition. The same experiment proved that the condition was not contagious. His later studies showed that diet could eliminate pellagra and that occurrences were related to poverty. Many officials across the South, however, refused to acknowledge the depth of the problem of hunger in the South and took no significant action for years.

The Flood of 1927, which devastated Arkansas and other portions of the lower Mississippi River Valley, heightened pellagra awareness as food availability worsened and tens of thousands of people abandoned their homes. Though the Red Cross had set up camps for the survivors, camps were segregated by race, and food supplies were slow in coming, often withheld by white landowners in order to coerce African-American sharecroppers and migrant farm workers into repairing the flood damage. As a result, cases of pellagra flared across the affected regions to more than 50,000 as malnutrition worsened. In Arkansas alone, 657 people died from pellagra in 1927.

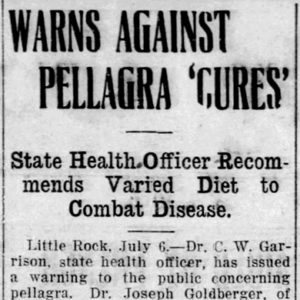

Yeast shipments quickly cured more than 4,000 cases across the South, prompting the Red Cross to heed Goldberger’s nutritional advice. In the late 1920s, the Red Cross conducted experiments in the Marked Tree (Poinsett County) area with powdered yeast to combat the condition. By 1937, researchers identified niacin as the key to pellagra prevention.

Niacin naturally exists in a wide variety of food products, including yeast, eggs, fish, green vegetables, and cereal grains. Niacin and B vitamins were quickly added to bread and other products. The Red Cross began distributing vegetable seeds to sharecroppers and tenant farmers. This, combined with campaigns through the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Arkansas Department of Agriculture promoting better nutrition and agricultural diversification, greatly reduced the cases of pellagra. By 1938, the number of pellagra deaths in Arkansas had dropped to 184, and it continued to drop in ensuing years. As the United States began to prepare for World War II, the federal government started to mandate vitamin supplementation of cereal products due to frustration with the number of draftees who were too malnourished for military service.

For additional information:

Barry, John M. Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America. New York: Touchstone, 1997.

Goldberger, Joseph, and Edgar Sydenstricker. “Pellagra in the Mississippi Flood Area: Report of an Inquiry Relating to the Prevalence of Pellagra in the Area Affected by the Overflow of the Mississippi and Its Tributaries in Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana in the Spring of 1927.” Public Health Reports 42 (November 4, 1927): 2706–2725.

Hegyi, Vladimir. “Pellagra.” eMedicine.com. http://www.emedicine.com/derm/topic621.htm (accessed April 27, 2022).

Tindall, George B. The Emergence of the New South, 1913–1945. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967.

Rattini, Kristin Baird. “The American South’s Deadly Diet.” Discover, July 18, 2018. Online at https://www.discovermagazine.com/health/the-american-souths-deadly-diet (accessed April 27, 2022).

West, Elliott, ed. The WPA Guide to 1930s Arkansas. Lawrence: University of Kansas, 1987.

Williamson, O. L. “Pellagra in Arkansas.” Journal of the American Medical Association 53 (August 28, 1909): 717.

Kenneth Bridges

South Arkansas Community College

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Food and Foodways

Food and Foodways Health and Medicine

Health and Medicine Bogus Cure

Bogus Cure  Pellagra Investigation

Pellagra Investigation  Pellagra Treatment

Pellagra Treatment

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.