calsfoundation@cals.org

Ozark Institute [Organization]

From 1976 until its end in 1983, the Ozark Institute (OI) created job programs, provided advocacy for a dwindling population of small farmers, and worked to create community organizations and institutions to help alleviate some of the hardships of rural life. Toward these aims, the OI partnered with the Office of Human Concern in Benton County, led by Bill Brown, a longtime resident of Eureka Springs (Carroll County). The OI created a host of entities and programs to aid the Ozarks region in its short life, including community canneries, the publication Uncertain Harvest, seed banks, job training programs, and the Eureka Springs radio station KESP.

The roots of the OI can be traced to the Conference on Ozark In-Migration in 1976, led by Edd Jeffords and others from around the Arkansas and Missouri Ozarks. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, nearly one million people throughout the United States left urbanized areas for rural settings, becoming “back-to-the-landers.” While many of these people moved to the Northeast or the West, which had long been centers of counter-cultural movements, a significant number were drawn to the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas. Somewhere between 2,000 and 6,000 back-to-the-landers moved to Arkansas between 1968 and 1982.

The Conference on Ozark In-Migration was an attempt by leaders, politicians, and pundits in the Ozark Mountains to understand the region’s changing population. Professors from the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) and the University of Central Arkansas (UCA) in Conway (Faulkner County), as well as authors and journalists such as Donald Harington, attended the multi-day discussions and panels. Multiple issues were discussed, but chief among them was a concern about the impact this rapid expansion would have on the Ozarks, both the land and the people.

After a meeting in Eureka Springs in November 1976, Ernie Deane and Jeffords oversaw the creation of a proposal for a nonprofit group that would become the OI. The mission of the new organization was to be a “public interest organization which will provide research and informational resources to individuals and organizations in North Arkansas and the Ozark Mountains,” with a focus on nutrition, energy, shelter, and culture.

Part of the mission of the OI was to help create or make available aids for the rural population of the Ozarks, particularly small farmers or family farmers (both natives and the back-to-the-land community). The OI’s efforts in this area centered around the creation and maintenance of community canneries. These were places in Benton, Carroll, and Madison counties where, for a small fee, people could come in with their produce and canning equipment and make use of a more efficient kitchen system than what they possessed themselves. By October 1978, some of the canneries were even incorporated with food co-ops, community gardens, and nascent farmers’ market systems across the three counties.

A second major output from the institute was the 1980 publication of Uncertain Harvest: The Family Farm in Arkansas. Edited by Jeffords and Ralph Desmarais, this volume was a collection of essays and statistics dealing with the plight of small farmers in Arkansas at the end of the 1970s, especially in relation to the growth of large-scale agribusinesses in the wake of changing agriculture policy during the 1970s. The book took to task the growing power of agricultural concerns such as Riceland and members of the state’s poultry industry. Uncertain Harvest prompted harsh criticism of the institute’s bias, as it used public funds for regional development work, but the book presented a picture of Arkansas agriculture at a crossroads, showing both black farmers and white farmers in the state at the time.

OI’s final notable creation was a public radio station located on the fourth floor of the Crescent Hotel in Eureka Springs. Created in the spring of 1979, Ozark Public Broadcasting, with the call sign KESP, was intended to be a volunteer and community-based radio station that broadcast music, events, and news to the surrounding area. The station operated for about two years, broadcasting community information, weather reports, small series on topics of local interest, and local music.

In 1980, Frank White mounted a challenge to Governor Bill Clinton, who had been a supporter of the OI from his days as the state’s attorney general. White and other Republicans in Little Rock (Pulaski County) alleged that the OI had misused funds and defamed or misrepresented major industries in the state, all of which prompted a Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) inquiry that ultimately turned up no evidence of mismanaged funds. By the time this ruling came down, it was too late. A new governor and a new political climate in Little Rock and Washington DC made it difficult for the OI to retain its federal and state funding.

Due to several factors—including the termination of the relationship between the Ozark Institute and the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulations that required KESP to shift from a ten-watt station to something larger, and a change in lease arrangements with the Crescent Hotel—the Ozark Public Broadcasting board announced in March 1981 that it would be closing KESP. By the end of 1982, Jeffords had resigned as executive director. As the OI began ceasing its operations, the canneries, always problematic financially, ceased their operations as well. The OI closed in 1983.

For additional information:

Luster, Mike. “Looking for the Center of the Universe: Edd Jeffords and Ozark In-migration.” Memorial Speech, 2006. Research files. Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, Springdale, Arkansas.

Ozark Institute Files. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Jared M. Phillips

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Ozark Mountain Folk Fair

Ozark Mountain Folk Fair Edd Jeffords

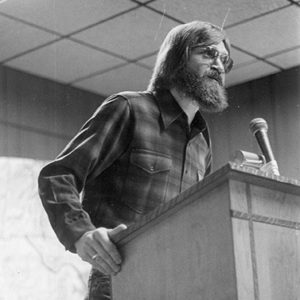

Edd Jeffords

I worked for Ozark Institute, building the KESP studio. I was the very first voice heard on KESP. I was the anchor/DJ for KESP. An audit showed that I had many more volunteer on-air hours than anyone else. I was also honored by being the very last voice heard on KESP when it signed off for its final broadcast.