calsfoundation@cals.org

Sebastian County

| Region: | Northwest |

| County Seats: | Fort Smith, Greenwood |

| Established: | January 6, 1851 |

| Parent Counties: | Crawford, Polk, Scott, Van Buren |

| Population: | 127,799 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 531.18 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

9,238 |

12,940 |

19,560 |

33,200 |

36,935 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

52,278 |

56,739 |

54,426 |

62,809 |

64,202 |

66,685 |

79,237 |

95,172 |

99,590 |

115,071 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

125,744 |

127,799 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

86,828 |

67.9% |

| African American |

8,061 |

6.3% |

| American Indian |

2,890 |

2.3% |

| Asian |

5,789 |

4.5% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

105 |

0.1% |

| Some Other Race |

10,404 |

8.1% |

| Two or More Races |

13,722 |

10.7% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

19,328 |

15.1% |

| Population Density |

240.6 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$46,228 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$25,961 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

18.5% |

|

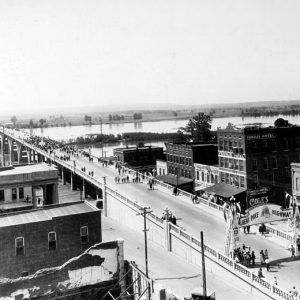

Sebastian County is located on Arkansas’s western border in the natural division known as the Arkansas Valley. The Arkansas River forms the county’s northern border, while its southern border touches upon the Ouachita Mountains. The county is home to Fort Smith, one of the state’s largest cities, as well as Fort Chaffee, and in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was the site of the state’s largest coal-mining operations. From the earliest days of the territorial period to the present, Sebastian County has served as a major transportation corridor to points west.

Pre-European Exploration

The Arkansas Valley region served as a place of residence to Native Americans since the last Ice Age, and there are hundreds of pre-contact settlement sites in Sebastian County alone. One of the more noteworthy sites is Cavanaugh Mound, which stands at a distance from other mounds and lacks evidence of a larger village complex nearby. The closest mound site to the Cavanaugh Mound is Spiro Mounds, about eight miles to the west in Oklahoma, and some archaeologists speculate that the Spiro complex could be seen from the top of Cavanaugh Mound and that the two sites were constructed by the same people. However, little scientific study has been conducted at Cavanaugh Mound, so there cannot yet be any determination made as to who built it or why.

European Exploration and Settlement

The expedition of Hernando de Soto through the American Southeast may have touched upon Sebastian County, according to a reconstruction of the expedition’s route by anthropologist Charles Hudson and his colleagues. Later, French trappers, travelers, and settlers gave names to such geographical features as the Poteau River and Belle Point, a bluff overlooking the Arkansas River. Massard Prairie may also take its name from French settlers.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Some Cherokee had been living in northeastern Arkansas until the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812 disrupted their settlements, leading them to move to western Arkansas. Additional bands of Cherokee immigrated to the Arkansas River area from their homelands in the eastern United States seven years later, joining already established Cherokee communities. American soldiers were dispatched to the area in 1817 under the command of Major William Bradford to keep the peace between Cherokee and Osage, who clashed over access to hunting grounds to the west. The fort these soldiers constructed at the confluence of the Poteau and Arkansas rivers, a place known as Belle Point, was named Fort Smith after the military district’s commander, General Thomas A. Smith. A second wave of Cherokee migration into the area the following year only exacerbated tensions, though U.S. government–facilitated negotiations between the Osage and the Cherokee in 1822 resulted in a slight reduction of violent encounters. Sequoyah, noted for his development of the Cherokee syllabary, lived in the Fort Smith area in the late 1820s.

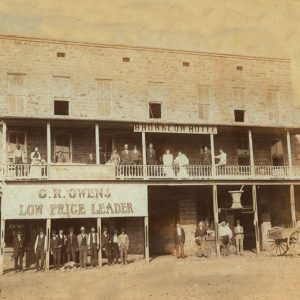

A settlement quickly grew around the fort, taking its name from the military establishment. Even when the army abandoned the fort, this settlement carried on, with trader John Rogers serving as something of a leader for the community. Aaron Barling, a former soldier, bought land eight miles east of Fort Smith in 1830. A small community known as Spring Hill grew up around his farm, though when the town sought incorporation later in the century, it did so under the name of its founder. Matthew Arbuckle, who served as commander of the troops at the fort, obtained more than 20,000 acres of land in Sebastian County for his service; this land eventually grew into the town of Lavaca. In 1836, the army returned to build its second post at Fort Smith. In 1838–1839, numerous Cherokee who had been expelled from their ancestral homelands in the East made their way through Sebastian County on what is known as the Trail of Tears. By the time of the California Gold Rush, steamboats were able to ply the Arkansas River to Fort Smith, and many people seeking riches out West disembarked at Fort Smith or nearby Van Buren (Crawford County) to travel the rest of the way by land. Future U.S. president Zachary Taylor commanded the garrison at Fort Smith from 1841 until 1844.

After the state legislature created Sebastian County on January 6, 1851, naming it after U.S. Senator William King Sebastian, county commissioners created the town of Greenwood, located centrally in the county, to serve as the county seat. Three years later, however, Fort Smith became the new county seat. In 1861, the state legislature divided the county into two judicial districts, thus making both cities into county seats, a situation that survives into the present day.

The county was the site of the first Catholic-related institution of higher education in Arkansas with the founding of St. Andrew’s College near Fort Smith in 1849, despite some anti-Catholicism efforts in the state. It continued operations until around 1860.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The 1860 federal census found 8,555 white citizens in the county with 680 enslaved people and a single free person of color. The county sent two representatives to the 1861 Secession Convention: William Meade Fishback and Samuel Griffith. Fishback was a Unionist who later served in the Federal army, while Griffith was a slaveowner with eleven enslaved people reported in the 1860 census.

Being on the western edge of Arkansas, Sebastian County was distant from other Federal outposts. Fearing that their situation was untenable, Federal troops abandoned Fort Smith on the eve of Arkansas’s secession from the Union. The county was spared military engagements until the September 1, 1863, Action at Devil’s Backbone, during which Union forces under Major General James G. Blunt were able to capture Fort Smith and drive Confederates under Brigadier General William L. Cabell to Waldron (Scott County). However, Union control of the area proved tenuous following the failure of the Camden Expedition in April 1864. At the July 27, 1864, Action at Massard Prairie, Confederates succeeded in capturing approximately 127 Union soldiers encamped south of Fort Smith. The success of this action prompted Brigadier General Douglas H. Cooper to test Union defenses at Fort Smith just four days later, but this was the last Confederate action against the city, which remained in Union hands until the end of the war. Other actions in the area include defense against the remnants of Price’s Missouri Raid and an attack on a foraging party south of Fort Smith on September 26, 1864.

Numerous units on both sides were organized in the county. The First Arkansas Light Artillery organized in the county in 1861 for service in the Provisional Army of Arkansas followed by service in the Confederate army. The Eleventh Regiment of United States Colored Troops organized at Fort Smith in 1863 and 1864, serving in Sebastian County and the Indian Territory for the remainder of the war.

At the conclusion of the war, officials from the federal government and delegates representing tribes in the Indian Territory met at Fort Smith to reestablish diplomatic relations.

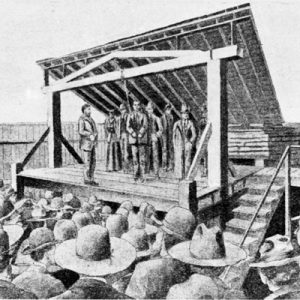

On March 3, 1871, the United States District Court for the Western District of Arkansas, which had jurisdiction not only over the western district but also Indian Territory west of the state, was moved from Van Buren to Fort Smith. Judge William Story was the first judge to preside in Fort Smith, but corruption was so prevalent that he eventually resigned.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

In 1875, Judge Isaac C. Parker was appointed to the bench at Fort Smith. He quickly established a reputation as a hard judge, sentencing numerous people to the gallows and thus acquiring the nickname of “hanging judge.” During his tenure, the court employed such legendary lawmen as Bass Reeves and Heck Thomas, who patrolled Indian Territory to serve warrants upon criminals who had taken refuge there. Fort Smith solidified its reputation as a frontier town of the Old West during this era.

Coal had been mined on a limited scale in Arkansas starting in the late 1840s in Johnson County, but coal was discovered in the Greenwood area in the 1870s and swiftly became the county’s chief industry, attracting not only investors but also immigrants of all varieties, especially eastern Europeans. That same decade, railroads arrived in Fort Smith, with the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad being completed in 1876, thus providing a convenient means of transporting coal out of the county. In 1889, the Iron Mountain and Southern Railroad constructed a line between Greenwood and Fort Smith. The St. Louis–San Francisco Railway reached Fort Smith in 1883, and the Kansas City Southern gave Fort Smith even greater national connections, just as it did the small town of Bonanza, which grew up around a mine established in 1896. In the late 1880s, the Little Rock and Texas Railway laid down track between the two communities of Coop Prairie and Chocoville on the border with Scott County, resulting in the merger of the two into the city of Mansfield, which also grew quickly as a hub for the shipment of coal. The discovery of natural gas in Sebastian County in 1887 also attracted investors and manufacturers to the area, though commercial development did not begin until 1902 near Mansfield.

A tornado in 1898 devastated Fort Smith, killing fifty-five people. Arising in Oklahoma, the tornado tore through the town before crossing the county.

Two incidents of racially based lynching took place in the county in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. An African American man known simply as Dumas was killed in 1874 after allegedly committing murder and escaping custody. In 1912, an African American man, Sanford Lewis, died at the hands of a mob after allegedly killing a law enforcement officer.

Early Twentieth Century

The twentieth century witnessed the continued growth of the coal industry in Sebastian County, though the growth was not without conflict. The United Mine Workers had organized strikes in 1888 and 1894, and, by 1903, had finally succeeded in obtaining a closed shop contract from local operators. This agreement lasted until 1914, when mine owner Franklin Bache tried to open a non-union mine near Frog Town. On April 6, 1914, miners and their sympathizers succeeded in shutting down the mine temporarily and driving off the non-union workers, but tensions continued to rise, and, in July, union miners battled with company guards at the site of one of Bache’s mines, while other mines in the area were dynamited during what has come to be called the Sebastian County Union War. The strike led to two U.S. Supreme Court cases titled Coronado Coal Co. v. United Mine Workers of America. Another notable strike took place in 1917 when women working as telephone operators walked off the job in response to the firing of two co-workers involved in union organizing.

Though Fort Smith has, throughout its history, possessed a small African-American community, much of rural Sebastian County has remained predominantly white, if not at times outright hostile to Black people. On the night of April 30, 1904, began what is now called the Bonanza Race War. Over a period of several days, white mobs in Bonanza fired upon the houses of Black miners and their families in an effort to drive away all Black miners, and the Arkansas Gazette reported that nearly all African Americans had left town by May 7. Bonanza thus became a known as a “sundown town,” as did other Sebastian County communities such as Greenwood.

Early efforts at higher education institutions in the county did not prove long lasting. Buckner College, for example, was in operation between 1882 and 1914. The Fort Smith School Board founded what would become the University of Arkansas at Fort Smith in 1928 as Fort Smith Junior College. The institution transitioned from a two-year college to a comprehensive university (part of the University of Arkansas System) offering multiple undergraduate degrees and selected graduate programs.

The city of Fort Smith managed to weather much of the hard times of the Great Depression through a diversified economy that featured furniture manufacturing, but much of rural Sebastian County was not so lucky, especially after a 1925 decline in coal prices led many of the operators to cut production and jobs in the area. However, some relief was to be found in New Deal agencies that worked in the county, such as the National Youth Administration, which built bridges and schools in the vicinity of Mansfield.

World War II through the Faubus Era

In 1941, Camp Chaffee (which later became Fort Chaffee) was established just outside Barling as a part of the U.S. Army’s preparations for World War II. During the war years, it served as both a training camp for the Sixth, Fourteenth, and Sixteenth Armored Divisions and a prisoner-of-war camp for approximately 3,000 Germans. The camp proved a boon for the town of Barling, as well as Greenwood, which abuts the camp to the south. In 1956, it was re-designated Fort Chaffee.

Though the creation of Camp Chaffee provided something of an economic stimulus to the county during the war, rural parts of the county faced a crisis as returning soldiers found few jobs in their hometowns. Residents of Lavaca found a way out of this crisis by growing what was called the Lavacaberry, a boysenberry-raspberry hybrid that proved popular not just with local consumers but also wholesalers. However, competition from out-of-state growers resulted in most farmers turning to other crops by the late 1950s.

Postwar economic troubles were not limited to rural areas, however. Camp Chaffee’s occasional deactivation and reactivation led Fort Smith’s leaders to attract a diverse array of industry so that the city’s economy would not be so dependent upon the military installation. In the 1950s and 1960s, they were successful in attracting numerous manufacturers to the city, most notably the Norge Company, which opened a plant in Fort Smith in 1962; this was later purchased by the Whirlpool Corp.

Modern Era

Fort Chaffee remains not only the economic lynchpin of the county but also has had a great cultural impact. In the mid-1970s, the fort was a processing center for more than 50,000 refugees of the Vietnam War. Some of these refugees remained in the county, founding one Laotian and two Vietnamese Buddhist temples within the city of Fort Smith. In 1980, the fort was a center for the processing of Cuban refugees; national attention was drawn toward the county after 2,000 to 3,000 refugees rioted in June to protest the conditions under which they were held. In 1997, command of the fort was transferred from the U.S. Army to the Arkansas National Guard, and portions of the base were turned over to the state for redevelopment, including commercial and industrial redevelopment. In 2005, the fort served as temporary housing for more than 10,000 evacuees from Louisiana, Texas, and Mississippi in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. The fort and surrounding locations also appeared in movies filmed in the 1980s, including Biloxi Blues and A Soldier’s Story.

Fort Smith remains a regional manufacturing center as well as a national transportation hub, especially since the completion of Interstate 40, which runs east-west across the United States from Wilmington, North Carolina, to Barstow, California, making the city a nexus of rail, river, and highway transportation. The city of Mansfield in southern Sebastian County is a local center for timber production, situated on the edge of the Ouachita National Forest. Many of the smaller towns serve as bedroom communities for the Fort Smith metropolitan area. These communities include Central City, Hackett, Hartford, Huntington, and Midland. In 2001, CDX Gas LLC began to develop coal-bed natural gas resources in the county, drilling thirty-seven horizontal wells and fifteen vertical wells for the extraction of natural gas. The Scott-Sebastian Regional Library System, headquartered in Greenwood, provides public library service to five branches in two counties.

The original Fort Smith site is now preserved as the Fort Smith National Historic Site. The U.S. Marshals Museum is located in Fort Smith. Numerous sites are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including the Coop Creek Bridge, Maness Schoolhouse, Greenwood Gymnasium, and the Belle Grove Historic District.

For additional information:

Bearss, Edwin C., and Arrell M. Gibson. Fort Smith: Little Gibraltar on the Arkansas. 2nd ed. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979.

The Goodspeed Histories of Sebastian County, Arkansas. Columbia, TN: Woodward & Stimson Printing Co., 1977.

Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society. Fort Smith, AR: Fort Smith Historical Society (1977–).

The Key. Greenwood, AR: South Sebastian County Historical Society (1966–).

Moore, Jerry H., and Lonnie C. Roach. No Smoke, No Soot, No Clinkers: A History of the Coal Industry in South Sebastian County. N.p.: Frank Boyd, 1974.

Spears, Jim. Justice Divided: A Judicial History of Sebastian County. Fort Smith, AR: Red Engine Press, 2022.

Wilkinson, Means. The First Hundred Years of Sebastian County. N.p.: M. Wilkinson, 1951.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.