calsfoundation@cals.org

Fort Smith Council

The gathering of Native Americans, Arkansas territorial officials, and U.S. government representatives held in 1822 at the confluence of the Poteau and Arkansas rivers—the event commonly referred to as the Fort Smith Council—was a laudable effort to establish amicable relations between Osage and Cherokee who were engaged in hostile actions that disrupted a large portion of the frontier region. The event actually had only limited success, but the face-to-face meeting of both Indian and territorial leaders, a rare event in territorial Arkansas, has become a popular fixture in stories about Arkansas’s early history.

When several bands of Cherokee settled along the Arkansas River upstream of Point Remove Creek in the spring of 1812, they established their communities in a nearly unpopulated region of Arkansas that had been given up as hunting territory by the Osage just over three years before. Over the next decade, this landscape was transformed politically and economically. A second wave of Cherokee migration in early 1818 brought hundreds of new settlers, as well as a new generation of leaders who had recently participated in U.S.-initiated Indian wars back east. White squatters, travelers, and traders encroached on Cherokee lands and increased the call for removing Indians from the territory. Tensions between the Cherokee and their Osage neighbors, especially over hunting rights and access to the southern Plains, fueled an increase in the frequency and scale of violent raids between the two Indian groups.

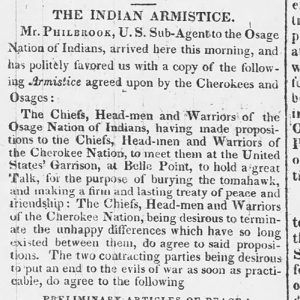

The U.S. government established a garrison at Belle Point, later Fort Smith (Sebastian County), in 1817 at the confluence of the Poteau and Arkansas rivers and populated it with a small military contingent charged with establishing peace in the region. Federal and territorial authorities, often with conflicting agendas, debated ways to relieve hostilities and promote white settlement. The Cherokee and Osage both sought political and economic relief from U.S. and territorial authorities, too, but raids continued. In order to resolve this problem, the U.S. government sent Colonel Matthew Arbuckle and a battalion of the Seventh Infantry to Fort Smith to bolster the military presence and provide leverage in negotiating a cessation of hostilities. Arbuckle consulted extensively with Governor James Miller at Arkansas Post (Arkansas County) on his ascent of the Arkansas River, and when he arrived at Fort Smith on February 26, 1822, he was immediately ready to find a resolution to the conflict.

Representatives of both tribes gathered at Belle Point on July 30, 1822, to work out a manageable strategy to resolve some of their current disputes and to establish ground rules for living in close proximity without provoking future violence. The large Osage delegation, reportedly numbering about 150, was led by three senior chiefs: Clermont, Tallai, and Bad Tempered Buffalo. The smaller Cherokee delegation included many of the leaders residing in Arkansas such as James Rogers, Young Glass, Thomas Maw, Waterminnow, Wat Webber, and John Martin. Military and civilian officials were present and also signed the treaty as witnesses, including Colonel Arbuckle, Captain Granville Leftwich, Governor Miller, Nathaniel Philbrook (who was the subagent for the Osage residing on the Verdigris River), David Brearly (the Arkansas Cherokee agent residing on the Arkansas River), and Epaphras Chapman of the United Foreign Mission Society of New York, who had established a mission among the Verdigris Osage two years earlier.

The treaty addressed three important sources of contention between the Cherokee and Osage: the fate of captives taken in previous encounters and now residing in enemy communities, the desire of both groups to have unimpeded access to hunting areas on the eastern Plains, and the fear of continued retaliatory raids by individuals of each tribe on members of the other. The treaty laid out procedures for captives to be returned to their homes and families, if they were willing to be repatriated, without further retaliation being visited on the captors. Over the years, some captives had been integrated into their new homes by marriage and adoption and were apparently not eager to be returned.

Several treaty provisions spelled out routes for both Osage and Cherokee hunters that would give them unimpeded access to the grasslands through each other’s territories without fear of attack. Members of both tribes were allowed to travel through each other’s lands north of the Arkansas River, and the Osage gave permission for Cherokee hunters to join them in hunting expeditions on land the Osage claimed south of the Arkansas River upstream from the mouth of the Poteau. Hunting parties were barred from establishing camps or other settlements on each other’s lands, however.

The final group of provisions addressed issues of private revenge raids and criminal activity. Aggrieved parties who suffered property loss or injury were to take their complaints to tribal agents, who were expected to arrange redress from the offenders and their respective tribal authorities. If no redress was forthcoming, the U.S. government, chiefly in the form of the Fort Smith garrison, was expected to step in and impose a resolution to the situation.

Governor Miller lost no time in taking credit for the treaty, both in correspondence to the secretary of war and in the local community. It is more likely that it was the high profile presence of Arbuckle’s soldiers, and the continuous attention of the two agents, that both precipitated the council and reaped the treaty’s limited benefits. For a while, retaliatory raids and violent encounters between Osage and Cherokee diminished, but they never disappeared entirely.

There were many reasons why the 1822 Osage-Cherokee treaty had a limited impact on the Arkansas frontier. Since the treaty was between two tribes, and not formally with the U.S. government, there was little political will beyond western Arkansas to impose its provisions. The treaty was never formally ratified. Political and economic factors in the rapidly developing territory soon made removal of all Indians from Arkansas a higher priority than maintaining a Cherokee presence on the Arkansas River. As the Osage, the Cherokee, and neighboring Eastern tribesmen encroached further upon resident southern Plains tribes, intertribal violence increased and occasionally swept up white travelers and settlers as well. The fate of the Arkansas Cherokee was also bound up in the greater political struggle among the U.S. government, several Southern states, and the Cherokee Nation, which ended in Cherokee Removal and made the 1822 council agreement at Fort Smith moot.

For additional information:

Bearss, Edwin C., and A. M. Gibson. Fort Smith: Little Gibraltar on the Arkansas. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969.

Carter, Clarence Edwin, ed. The Territorial Papers of the United States. vol. 19, The Territory of Arkansas, 1819–1825. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1953.

Hoig, Stanley W. The Cherokees and Their Chiefs. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Ann M. Early

Arkansas Archeological Survey

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.