calsfoundation@cals.org

Mining

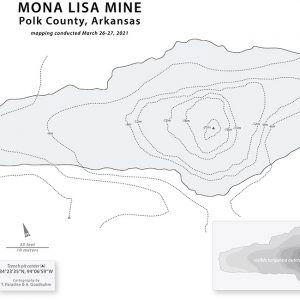

Mining is defined as the extraction of valuable minerals or stone (mineral resources) from the earth, usually from an ore body, vein, or bed. Materials mined in Arkansas include base metals, iron, vanadium, coal, diamonds, crushed and dimension stone, barite, tripoli, quartz crystal, gypsum, chalk, and bauxite.

Mineral resources are non-renewable, unlike agricultural products or factory-produced materials. Mining in a wider sense includes extraction of any non-renewable resource, including petroleum, natural gas, bromine brine, or even water. These resources are recovered by extractive methods that differ from those of normal surface or underground “hard rock” mining methods.

Early settlers in the Arkansas Territory used several local mineral commodities. These included galena (lead ore), hematite and goethite (brown iron ores), saline brines (for salt), coal (for blacksmith forges), and saltpeter (for the manufacture of black gunpowder). These resources were economically viable early in the region’s history. All but coal have not been mined for decades. Diamonds were discovered in Pike County in 1906, and sporadic mining continued from then until the start of the Great Depression.

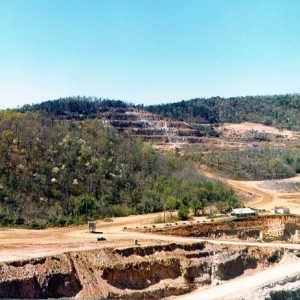

Modern mining processes involve prospecting for ore bodies, analyzing the profit potential of a proposed mine, extracting the desired materials, and ultimately reclaiming the land to prepare it for other uses once the mine is closed. Modern mining technologies allow the profitable and safe recovery of minerals with little long-term negative impact to the environment.

Recent Significant Mining Activity

Since the early 1940s, certain mineral commodities have been economically significant in Arkansas. Mining of bauxite for aluminum and alumina began in the 1890s and reached its peak during World War II. It continued with significant extraction until 1991, when production of metal ceased due to economic factors. Certain metals had their production peaks during major wars or military conflicts, including antimony in Sevier County (1916–1918), mercury in Pike County (1939–1945), lead in the Ozark Mountains and Ouachita Mountains (1917–1918, 1940–1945), zinc (same years as lead), and manganese in Izard, Independence, Montgomery, and Polk counties (1940–1956). The federal government typically considers certain materials to be strategic and critical during such times. The last half of the twentieth century also saw declining tonnages of coal extracted in the Arkansas River Valley region and a drastic reduction of the number of producers, principally due to increased regulation by the federal government brought on by environmental concerns.

Demand for certain minerals is tied to various economic activities, not necessarily related to war, such as the use of barite in drilling muds, as well as increased levels of petroleum and natural gas drilling. During the years of barite production (1940 to the mid-1970s), Arkansas often ranked as the number-one producer in the United States. Vanadium was discovered in Garland and Hot Spring counties by 1940, and production began in the early 1970s, continuing until 1991. Vanadium pentaoxide is an important steel additive, imparting to steel the ability to hold a sharp edge. The production of clay for bricks began across the state due to local community needs early in the nineteenth century and has now evolved to the production of high-quality decorative and structural brick products by one major company in Hot Spring County. The mining of gypsum and manufacture of wallboard is directly tied to the cycle of the building trades. The largest manufacturing plant for wallboard in the world is located near Nashville (Howard County). Major production of wallboard began in 1963, and production has been continuous since that time. The operation has undergone several ownership changes and is presently owned by a French company. The wallboard plant capacity was doubled within the past few years to a capacity of more than 1.4 billion square feet per year. Mining of chalk for the manufacture of cement has been continuous near Foreman (Little River County) since 1958. Recent renovations of that facility make it the largest-capacity American-owned cement plant in the country. Cement is used as the binding agent in concrete in both highway construction and the building trades, and as such, production is dependent on the economic activity of the country.

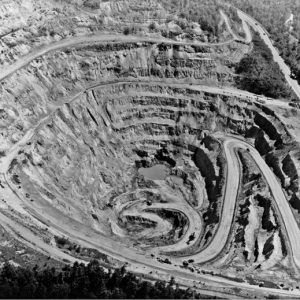

Aggregate has been in demand since modern road building began in Arkansas, starting with the first paved state highways in the early twentieth century and increasing dramatically with the beginning of construction of the federal interstate highway system in 1956. Construction of highways at the county, state, and federal levels drives both the crushed stone and sand/gravel industries in Arkansas. At least seventy-five percent of Arkansas counties have production of one or both of these commodities. Crushed stone for highway aggregate may consist of sandstone, limestone, dolostone, novaculite, syenite, and tuff, produced in the Interior Highlands of Arkansas. In the Gulf Coastal Plain, sand and gravel are mined where hard rock is not available to crush, particularly for local projects. The high cost of transportation precludes shipping these lower-cost materials any significant distance. Starting in the 1990s, both the crushed stone and sand/gravel businesses have undergone significant changes in the state. A few major companies, not based in the state, account for most of Arkansas’s production of aggregate. A few smaller, locally owned mines scattered across the state are able to supply county road departments and small users, which saves transportation costs.

A specialty use of crushed stone, both syenite and well indurated shale, is the manufacture of roofing granules. Large-scale operations in the Little Rock (Pulaski County) area began in 1947. Roofing granules are also made from crushed shale in Montgomery County. Roofing granules are attached to fiberglass or tarpaper shingles and help keep sunlight from degrading the asphalt.

Dimension stone production began locally wherever high-quality workable rock was minable during the early part of the nineteenth century. Stone masons used bedded sandstone, limestone, and dolomite that could be quarried and worked by hand for the construction of many public projects like county courthouses and bridges, and for some privately owned projects like large hotels and resort communities. Towns such as Hot Springs (Garland County) and Eureka Springs (Carroll County) have buildings built from locally produced stone. Historically, some hand-hewn dimension stone was produced from syenite quarries near Little Rock, along with river riprap and monuments, but due to increased labor costs and the demand for this rock as crushed aggregate, the use of this rock changed in the late 1940s. Many small quarry operations in the Arkansas River Valley currently produce from thinly bedded sandstones. The rock is typically quarried as plates from two to twelve inches thick and then broken by machine to the required other dimensions. Much of this stone is marketed out of state.

Silica production in Arkansas consists of the mining of several mineral resources, including silica sand (a.k.a. industrial sand), novaculite, silica pebble, tripoli, and quartz crystals. Silica sand consists of high-purity quartz sand that is principally used for manufacture of glass, along with “frac” sand for Fayetteville Shale gas production and foundry sand for metal casting. Silica sand is produced from Independence County from Ordovician age sandstone and from Sebastian County as a byproduct of construction sand dredged from the Arkansas River. Novaculite is produced in Garland and Hot Spring counties and is a unique natural resource from Arkansas. This high-silica rock can be used for many things, including use as a silica source for the production of silicon metal and for the production of laboratory glassware (Pyrex). Several companies actively mine novaculite for the manufacture of various grades of whetstones and abrasive stones near Hot Springs. The manufacture of oilstones and whetstones has been continuous for more than 100 years. Predating that, archaeologists have discovered quarry sites in the area that date back more than 1,000 years, making the quarrying of novaculite Arkansas’s oldest mineral industry. Silica pebble is produced from one mine south of Sheridan (Grant County) and has specialty uses in architectural applications and as an aggregate in kitchen countertops. Tripoli is very fine-grained, natural silica that is used for abrasives and as plastic and paint fillers. One company mines it from locally altered deposits within the Arkansas Novaculite and Bigfork Chert formations in Garland County.

Arkansas also has deposits of hydrothermal quartz crystals within the sedimentary rock formations of the Ouachita Mountains. Considered world-class deposits, many sites were investigated by the federal government during World War II. Prior to that time, mining of quartz crystal was done mostly by farmers during the winter who brought crystals to Hot Springs to sell to the many visitors. The portion of quartz-mining business related to tourism grew rapidly in the 1980s and 1990s. At least ten mines are now open to tourists for crystal collecting, and many visitors participate in this family-oriented activity while vacationing in the area. Quartz mining has been a predominately family-operated business, passed down from one generation to the next. However, some foreign investors, including the Japanese and Germans, were active at a mine north of Hot Springs for several years, mining a quartz product termed “lascas.” Lascas is the chemical feedstock used to grow synthetic quartz for many industrial applications. Quartz crystal production continues for the tourist trade, museums, and collectors.

Since the discovery of bromine brine in Columbia and Union counties in south Arkansas, the state has been the major producer of bromine in the United States, accounting for ninety-seven percent of national production and forty percent of the world’s production. Technically, this industrial mineral is extracted by drilling and removal of bromine-bearing salt water, but it is considered an industrial mineral because it is not a petroleum byproduct. Bromine is used in many industrial applications, including fabric fire retardants, medicines, and herbicides and pesticides.

Economic Impact

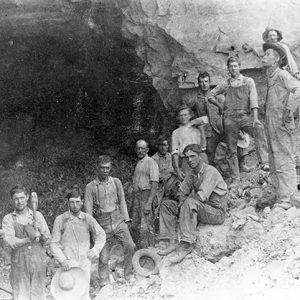

Mining in Arkansas has provided needed jobs and higher-than-average wages. Early non-mechanized mining jobs were labor intensive, particularly in the coal, early metals, and stone mining industries. While labor intensive, early mining served as a base industry upon which many who moved to the state depended. As technology improved with the increased use of better-engineered equipment and mine design, mining became safer and somewhat less physically demanding. The number of actual mining jobs began to decline while productivity of miners increased dramatically.

Although many consider Arkansas an agricultural state, it has for years ranked twenty-fifth or twenty-sixth in the nation in mining. The mining industry in the state produces a significant number of minerals and products made directly from local mineral resources.

As of 2009, mining jobs have average wages close to $45,000 per year, thirty-two percent higher than average state wages. Some 3,670 jobs in Arkansas are in the mining business, with several thousands of others dependent on mining in the roles of suppliers of fuels, equipment, lubricants, and mining-related materials. Production of industrial minerals over the period from 2004 to 2006 has been valued at approximately $500 million annually by the U.S. Geological Survey. Of the many minerals produced in the state, four make up ninety-two percent of the value: bromine brine, crushed stone, cement, and sand/gravel, in that order of value.

For additional information:

Arkansas Geological Survey. https://www.geology.arkansas.gov/ (accessed April 18, 2022).

“Arkansas States Mineral Information.” U.S. Geological Survey. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/state/ar.html (accessed April 18, 2022).

Howard, J. M, G. W. Colton, and W. L. Prior, eds. Mineral, Fossil Fuel, and Water Resources of Arkansas. Arkansas Geological Commission Bulletin 24. Little Rock: Arkansas Geological Commission, 1997.

Reynolds, Terry S. “A False Glimmer of Hope: The Rise and Fall of Arkansas’s Mercury Mining District, 1931–1946.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 81 (Winter 2022): 339–367.

Stroud, R. B., R. H. Arndt, F. B. Fulkerson, and W. G. Diamond. Mineral Resources and Industries of Arkansas. U.S. Bureau of Mines Bulletin 645. Washington DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1969.

J. Michael Howard

Mabelvale, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.