calsfoundation@cals.org

Mercury Mining

aka: Cinnabar Mining

Mercury, which was first mined in Arkansas in 1931, is in most rock types in trace amounts, generally occurring at higher levels in shale and clay-rich sediments and organic materials like coal than in sandstone, limestone, or dolostone. Although mercury was widely used in the past for several applications, the market for products containing mercury steadily declined in the 1980s because it was recognized to be toxic. It still has important uses, however, in the chemical and electrical industries as well as in dental applications and measuring and control devices.

The mercury-bearing district in southwest Arkansas occupies an area six miles wide by thirty miles long, extending from eastern Howard County through Pike County and into western Clark County. Surface rocks in the mercury district are sandstone, shale, and siltstone of the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian Systems (Paleozoic). The Paleozoic rocks were highly deformed by both folding and faulting during the Ouachita orogeny. In the southern portions of the previously mentioned counties, these rocks are now covered by Cretaceous clay, sand, gravel, and limestone beds. Erosion of the Paleozoic rocks has resulted in steeply dipping, generally east-west trending ridges and valleys. Cinnabar and other primary minerals were deposited by hydrothermal aqueous solutions rising through the fractured Paleozoic rocks near the end of the mountain-building processes, some 245 million years ago. Associated minerals consist of dickite (a hydrothermal clay), quartz veins, pyrite, and rarely stibnite.

Ore bodies in the mercury district occur as pipe-like bodies in association with minor folds and cross faults, and as tabular bodies generally restricted to an individual sandstone bed or a small group of beds. Mineralizing fluids deposited the ore minerals in open fractures, fault breccias, and sparingly in pore spaces in the associated sandstone. The mercury deposits are discontinuous and irregular in both vertical and horizontal outline. In general, small pockets of rich ore were more common in the western part of the district, whereas large bodies of disseminated ore were noted in the eastern part.

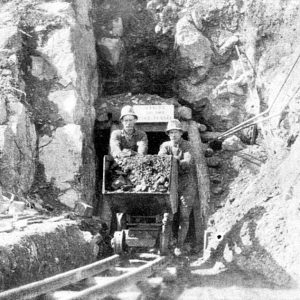

Cinnabar, or mercury sulfide, is the principal ore mineral and was first discovered in southwestern Arkansas in 1930. Prospecting along the major trends of larger faults in the area was conducted by examination of outcrops, pitting, trenching, restricted core drilling, and some geochemical sampling. Mining, by both surface and underground methods, began in 1931, and mercury was recovered yearly through 1944. At any given location, few ore reserves were established due to lack of organized exploration. Minor, but rich, placer cinnabar was recovered at the Parker Hill mill site in Pike County and added to the primary ore before roasting.

Most of the cinnabar mines were in Pike County. Within the three-county area, there were some sixty-seven mines and prospects, along with hundreds of small exploration test pits and trenches. Although more than 100 occurrences of cinnabar have been discovered across the district, only ten mines accounted for most of the production.

The production of mercury was important during World War II, as mercury fulminate is essential for bullet primers and the world’s largest producing area, in Spain, was under the control of dictator Francisco Franco. Also, other compounds of mercury find use in tracer bullets and chemical warfare compounds. Domestic production—mostly from 1941 to 1944—aided the war effort in the United States. During the war years, the price per flask averaged approximately $380 (in 1960 dollars) per seventy-six-pound flask, the standard unit of sale for native mercury.

Cinnabar was roasted in the presence of oxygen to break the mineral down into free mercury vapor and sulfur dioxide. These gases were then cooled and the mercury condensed as a liquid, being recovered in retort facilities. Refining from 1931 to 1944 yielded approximately 11,400 such flasks. Since 1946, the only reported production was twenty-seven such flasks from a retort located one mile south of Kirby (Pike County) on State Highway 27. These additional flasks were recovered in 1965 from low-grade ores that were previously mined. Mining has been negligible since 1946.

For additional information:

“Metallic Minerals.” Arkansas Geological Survey. https://www.geology.arkansas.gov/minerals/metallic-minerals.html (accessed January 24, 2022).

Branner, G. C. “Cinnabar in Southwestern Arkansas.” Arkansas Geological Survey Information Circular 2. Little Rock: Arkansas Geological Survey, 1932.

Cinnabar Mining in Southwest Arkansas. Arkadelphia, AR: Clark County Historical Association, 2023.

Clardy, B. F., and W. V. Bush. “Mercury District of Southwest Arkansas.” Arkansas Geological Commission Information Circular 23. Little Rock: Arkansas Geological Commission, 1976.

Gallager, David. “Quicksilver Deposits near the Little Missouri River, Pike County, Arkansas.” U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 936-H. Washington DC: U.S. Geological Survey, 1942.

Reed, J. C., and F. G. Wells. “Geology and Ore Deposits of the Southwestern Arkansas Quicksilver District.” U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 886-C. Washington DC: U.S. Geological Survey, 1938.

Reynolds, Terry S. “Arkansas’s Tri-County Mercury Mining District, 1930–1945: A Historical Overview.” Clark County Historical Journal (2024): 89–106.

———. “A False Glimmer of Hope: The Rise and Fall of Arkansas’s Mercury Mining District, 1931–1946.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 81 (Winter 2022): 339–367.

Stroud, R. B., R. H. Arndt, F. B. Fulkerson, and W. G. Diamond. “Mineral Resources and Industries of Arkansas.” U.S. Bureau of Mines Bulletin 645. Washington DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1969.

J. Michael Howard

Mabelvale, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.