calsfoundation@cals.org

Izard County

| Region: | Northeast |

| County Seat: | Melbourne |

| Established: | October 27, 1825 |

| Parent County: | Independence |

| Population: | 13,577 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 580.18 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

1,266 |

2,240 |

3,213 |

7,215 |

6,806 |

10,857 |

13,038 |

13,506 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

14,561 |

13,871 |

12,872 |

12,834 |

9,953 |

6,766 |

7,381 |

10,768 |

11,364 |

13,249 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13,696 |

13,577 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

12,306 |

90.6% |

| African American |

256 |

1.9% |

| American Indian |

87 |

0.6% |

| Asian |

27 |

0.2% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

11 |

0.1% |

| Some Other Race |

123 |

0.9% |

| Two or More Races |

767 |

5.6% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

326 |

2.4% |

| Population Density |

23.4 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$42,876 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$21,164 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

15.1% |

|

In the nineteenth century, Izard County served as a gateway to settlement across northern Arkansas and was the parent county of seven other counties. Later, Izard County’s virgin yellow pine forests provided lumber to other parts of the state. Today, the county houses a state prison and is a tourist and retirement destination.

Izard County has not changed a great deal since the settlers first arrived. Then and now, oak and pine forests cover much of the southern Ozarks hills. The county’s highest elevations are in the Boswell and Sylamore area. These include Brandenburg Mountain (1,099 feet), Thompson Mountain (1,124 feet), and Pilot Knob (1,123 feet). The county has sixty-eight named streams, all of which flow eventually into the White River. Limestone bluffs grace parts of Piney Creek and the White River. Grassy valleys are dotted with small towns, the largest being Horseshoe Bend, Melbourne, Calico Rock, Oxford, and Mount Pleasant.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

According to some historians, John Lafferty, a native of Ireland, traveled up the White River in 1802 to what became known as Lafferty Creek. He built a log cabin and attempted to claim 640 acres following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, but his claim was denied because he had not lived on the land for ten years. In spite of this setback, Lafferty and his family established the county’s first settlement at Lafferty Creek in 1810. Osage hunted in the area prior to an 1808 treaty, and Shawnee also lived in the White River valley until 1833.

Pure water springs, abundant game and fish, tall grass prairies, virgin pine forests, and the absence of disease-bearing mosquitoes attracted settlers from Tennessee, Kentucky, and the Carolinas. Augustus C. Jeffery wrote of the place, “From 1815 to 1820… the White River valley was overrun by… hunters, stock raisers, horse thieves, murderers, and refugees from [Eastern] prisons.” But “about 1827, a revival of religion commenced under the preaching of the Baptist, Methodist, and Cumberland Presbyterian churches.” Baptist preacher George Gill held services at one Colonel Stewart’s house on Piney Bayou (near present day Boswell) from 1814 to 1820. In 1823 and 1824, Cumberland Presbyterian missionary John Carnahan preached along the White River. In 1826, Jehoiada and Daniel Jeffery chartered the Mount Olive Cumberland Presbyterian congregation, which still meets. These original three denominations still predominate in Izard County.

In 1825, the territorial government split off part of Independence County, naming the new county for Governor George Izard. Adding Osage (1827) and Cherokee (1828) lands, Izard County covered most of north-central Arkansas. In 1833, western Izard County was divided into Van Buren, Carroll, and Johnson counties. Later, sections of Izard County were split off to become Marion (1836), Fulton (1842), and parts of Baxter (1873) and Stone (1873) counties.

Izard’s first county seat and post office (then called Liberty, now Norfork in Baxter County) were established at the mouth of the North Fork River at Jacob Wolf’s trading post. Sheriff John Adams and Clerk John Houston (brother of Sam Houston) were the first elected officials. The county seat was moved to Athens in 1830 and to Mount Olive in 1836. Mill Creek (later renamed Melbourne) became the county seat in 1875. Courthouses there burned in 1889 and 1937. From 1938 to 1940, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) from Camp Sage (near Sage) built the current courthouse. It is the only courthouse in the country partly heated by a wood-burning furnace. In 2003, residents approved a sales tax increase to build a new jail in Melbourne.

In December 1838, about 1,200 Cherokee traveled across Izard County on the Jacksonport Military Road on what became known as the Benge Route of the Trail of Tears. The Indians were being removed from Alabama to the Oklahoma Indian Territory.

Keelboats began bringing settlers up the White River in the early 1800s. By 1844, steamboats were traveling the White River as far as Izard County, bringing in passengers and mail and leaving with cash crops. As a result, the county’s population increased from 1,266 in 1850 to 7,215 in 1860. Steamboats made regular stops at Guion and Calico Rock. From the 1820s, virgin yellow pine was harvested, some with slave labor, and floated down river or taken by steamboat.

The 1860 census shows only five foreign-born residents in Izard County: four from Ireland and one from Germany. Those not born in the county came primarily from Tennessee, the Carolinas, and a few from Kentucky and Mississippi. Most were of English, Scotch, or Scots-Irish heritage. In 1819, Jehoiada Jeffery brought the first slaves to live in the county. By 1860, there were 382 enslaved African Americans living in Izard County alongside 6,831 white citizens.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Most county residents opposed secession. Alexander Adams, the county’s representative in the state legislature, voted against secession until the final vote. He was one of the last four holdouts at the Secession Convention. In May 1861, the Mill Creek Peace Organization Society was formed with the aim of keeping peace in the county and maintaining neutrality in the coming war. That November, Governor Henry Massie Rector ordered the county’s state militia and the Third Arkansas Cavalry to arrest members of the group. Society members who resisted were shot. The ninety-seven who were arrested either joined the Confederate Eighth Arkansas Infantry or were sent to prison at Little Rock (Pulaski County).

When the state left the Union, Izard County organized two companies; one for the Seventh Arkansas Infantry and one for the Fourteenth Arkansas Infantry. Early skirmishes between rebel and Union troops occurred at Calico Rock Landing (May 26, 1862), Sylamore (May 29, 1862), and Mount Olive (June 17, 1862). Confederate Colonel Thomas R. Freeman led his bushwhackers against Union troops in skirmishes north of Oxford (December 10, 1863) and at Lunenburg (January 20, 1864). In January 1864, Union troops under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William Baumer were ordered to hunt down Freeman. The troops attacked Mount Olive and Sylamore, burning both towns. The Wild Haws Expedition took place in the county in March 1864 but did not lead to any engagements.

During the war, jayhawkers and bushwhackers inflicted the greatest devastation to the county. In May 1862, Union General Samuel Curtis, headquartered at Batesville (Independence County), ordered his troops to sieze horses, mules, cattle, crops, and money, and to burn whatever was left. Property tax records for 1861 show the county had 5,618 cattle and 1,614 horses; by 1865, only 2,017 cattle and 501 horses remained.

After the war, many people starved in Izard County, resorting to eating grass and bark. Crops did not return for two years. During Reconstruction, life was difficult for freed slaves. Lack of work, discrimination, and the Ku Klux Klan and “regulators” drove many African Americans out of the county. By 1870, the black population had dropped to 164 people.

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

In the late nineteenth century, county agriculture consisted mainly in raising corn, wheat, vegetables, sorghum, and tobacco, as well as cattle and pigs for local consumption. Cash crops were cotton, corn, wheat, pork, beef, and pine timber. Residents supplemented their farm produce with fish, wild game (deer, razorback hogs, bear, and smaller game), mussels from the White River (finding an occasional pearl), berries, and nuts (chinquapin, walnuts).

Women spun cotton thread and made cloth on looms. Besides farming, residents found employment as lumberjacks or in local gristmills, cotton gins, sawmills, and general stores.

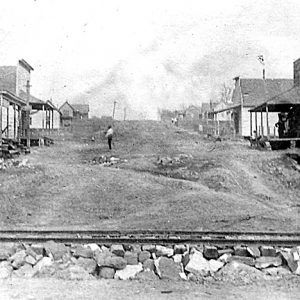

In 1903, the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad (which later became the Missouri Pacific) reached Calico Rock along the northern bank of the White River. Soon after, steamboat traffic on the river ceased.

Early Twentieth Century through Modern Era

In 1909, Arkansas Silica Sand Corporation (now UNIMIN Corporation) opened a silica sand mine at Guion. The ninety-nine percent pure silica sand is used in glass production. Arkansas Aircraft (later Douglas Aircraft) opened a fabrication plant near Melbourne in 1964, which brought the county’s first union (UAW Local 1482) in 1967. The Boeing Company operates the plant today.

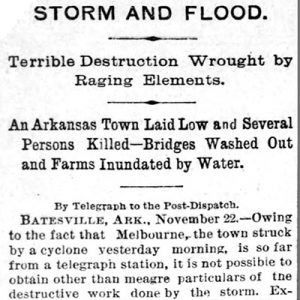

Weather conditions brought droughts in 1901, 1930, and 1934, serious flooding along the White River in 1915, 1927, and 1982, and a hard freeze in 1917–18. Tornadoes damaged Calico Rock (1866), Franklin (1933), LaCrosse and Jumbo (1936), and Sylamore (1997) and leveled Guion (1929).

From the 1920s through the 1950s, farming became less viable, and many county residents moved to Oklahoma or Texas. During the Depression, others went to the state of Washington to work in the apple orchards, some returning home after harvest. Cotton farming died out after World War II. Today, poultry and cattle are the county’s largest farming operations.

In 1941, work began on Norfork Dam to provide hydroelectric power and to prevent flooding on the White River. With the river under control, the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission began stocking the river with trout. Publicity about fishing on Lake Norfork and the White River, opening deer season to hunters from outside the county, and the development of tourist attractions in nearby counties gradually increased tourism until, today, it is one of Izard County’s chief industries. Since the 1970s, many newcomers and former residents have retired to Izard County. Begun in 1960, Horseshoe Bend is a planned community built around seven lakes, a golf course, and an airport.

The 1974 film Bootleggers was filmed in the county.

In 1990, the Arkansas Department of Corrections opened the North Central Unit north of Calico Rock. It became the county’s largest employer, with a capacity to hold 800 prisoners by 2022.

Education and Healthcare

The county’s first private school opened at Mount Olive about 1823. Many pastors taught such “subscription” schools, using their church meetinghouses for classrooms. Private boarding academies for higher education were established at Mount Pleasant (1885–1908), Philadelphia (1870–1905), and Mount Olive (1866–1875). Typical of these academies was LaCrosse Collegiate Institute, begun in 1868 at LaCrosse. Students came from Izard County, other counties, and even other states. They boarded with local families for the nine-month term. It closed in 1902.

Free public education in Izard County began in 1875 at Lunenburg. By 1899, Izard County had ninety-four rural school districts. Through consolidation, the county today has three districts, with high schools at Melbourne, Brockwell, and Calico Rock. Melbourne’s Ozarka College opened in 1975 as a vocational technical school and has the first accredited culinary arts program in the state. The Izard County Library opened in Melbourne in 1951, the Calico Rock Library reopened in 1959, and the Horseshoe Bend Library opened in 1974. The Brockwell Gospel Music School offers courses each summer in singing and the playing of instruments.

Mount Pleasant had the county’s first hospital (1928–1941). A twenty-bed hospital operated in Melbourne from 1948 to 1956. In July 1959, Dr. Meryl Grasse and John Grasse opened a ten-bed hospital in Calico Rock. This has grown into the thirty-bed Community Medical Center of Izard County, with clinics in Calico Rock, Horseshoe Bend, and Melbourne.

Famous Residents

Izard County has been home to many people who have become successful beyond the county limits. Robert Emmett Jeffery was a member of the Arkansas House of Representatives and a circuit court judge before President Woodrow Wilson appointed him as U.S. minister to Uruguay from 1915 to 1921. Samuel Billingsley Hill moved to the state of Washington in 1904 and served in the U.S. Congress from 1923 through 1936; he was also a judge on the U.S. Board of Tax Appeals (now the Tax Court of the United States) until 1953. Edward Baxter Billingsley served in the U.S. Navy, reaching the rank of rear admiral before his retirement. Vada Webb Sheid, the first woman to serve in both chambers of the Arkansas General Assembly, was born in Izard County. Elwin Charles “Preacher” Roe, who was born in Ash Flat (Sharp County) and grew up north of Pineville, was an all-star pitcher for the Brooklyn Dodgers and Pittsburgh Pirates from 1938 to 1954.

For additional information:

Blevins, Brooks. Hill Folks: A History of Arkansas Ozarkers and Their Image. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Izard County Historian. Melborne, AR: Izard County Historical & Genealogical Society (1970–1989, 1996–).

Shannon, Karr. A History of Izard County. Little Rock: Democrat Printing & Lithographing, 1947.

Stowers, Juanita. The History and Families of Izard County, Arkansas. Paduchah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 2001.

Wolf, John Quincy. Life in the Leatherwoods: An Ozark Boyhood Remembered. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1974.

Susan Varno

Dolph, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.