calsfoundation@cals.org

Plumerville Conflict of 1886–1892

During the late 1880s, electoral politics in Conway County turned violent, resulting in serious injuries and several deaths. In the Plumerville (Conway County) community, actions such as voter intimidation and the theft of ballot boxes were flagrant and seemingly condoned by public officials. The violence became widely known and was the subject of a federal investigation after the assassination of a congressional candidate, John Clayton. A pattern of local political affiliations and latent hostilities toward other factions developed and remained well into the twentieth century.

While the political conflict renewed itself after the 1884 election, the underlying causes date back to the pre–Civil War days. Conway County was a small version of Arkansas in terms of geographic culture and economics. The northern part of the county was composed of highlands and held small subsistence farms, while the Arkansas River bottomland supported a cotton-based slaveholding economy. There was lively debate in the area regarding secession, but the county chose Dr. Samuel J. Stallings, who favored a vote against secession, as the delegate to the convention in Little Rock (Pulaski County). However, after the attack upon Fort Sumter in South Carolina, regional pressures forced Stallings to vote for secession.

During the war, several Confederate and two Union companies were raised within the county. There were a number of skirmishes in Conway County, and the area was contested by guerrilla actions throughout the war. The Union occupation of Lewisburg (Conway County) and the burning of the county courthouse in Springfield (Conway County) by Union forces hardened the attitudes of many for years to come. Associated with both of these events, and particularly disturbing to some, were the actions of Captain Thomas Jefferson Williams, a local of northern Conway County. He commanded an independent Union company of scouts and spies, sometimes known as Williams’s Raiders, which created havoc for Southern sympathizers and helped enforce strong occupation rules in Lewisburg. Captain Williams became a personal target, and he was killed at the front door of his home in Center Ridge (Conway County) near the end of the war.

During the Reconstruction period, Conway County again became embroiled in its own civil conflicts. In December of 1868, martial law was declared in Lewisburg after residents—both white and black—were lynched by warring factions. The reconstituted Williams militia from Center Ridge once again was found in the center of the conflict, along with an organized African-American militia. Earlier that year, in August, Governor Powell Clayton, himself having authorized the armed locals, was required to travel to Lewisburg to intercede and quell the violence.

Once the Democrats regained power in the 1872 election, the county seat was moved from Springfield back to Lewisburg. Additionally, the Republicans of the northern areas and the former slaves of the bottomland plantations were relegated to isolated minorities. Over the next twelve years, changes began and the balance of power shifted once more. Of particular importance was the influx of large numbers of migrants from east of the Mississippi River. The percentage of African Americans in the county had grown from less than seven percent before the war to over thirty-nine percent by 1890, being drawn largely by cheap railroad land and agricultural work. Of course, the men could vote, and they became a vital voting bloc for the Republicans. Most of the “colored vote” came from black citizens of Howard Township, composed of Plumerville and Menifee (Conway County), who worked in the cotton fields. Five other minority communities were established, some in the northern hill country.

Also during this period, two significant agrarian movements, the Agricultural Wheel, founded at Des Arc (Prairie County), and the Brothers of Freedom, organized in west-central Arkansas, served to gather the isolated hill farmers into functional political organizations. The two organizations held a statewide merger meeting in Springfield in December 1884. Reactionaries on both sides of the merger question sought to use these groups to rekindle old cultural and economic divisions, given that these groups somewhat aligned themselves with local Republicans (and later formed a fusion ticket in 1888).

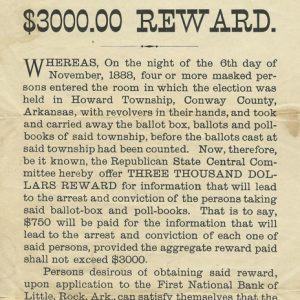

The federal election of 1888 was heavily contested, and accusations of voter fraud and the theft of a ballot box led to the murder of John Clayton, the Republican candidate for Congress and brother of the former governor, while he was in Plumerville investigating allegations of election fraud in 1889. Cover-ups, intimidation, beatings, and the attempted murder of federal officials resulted. A prominent black legislator, the Reverend G. E. Trower, was forced at gunpoint from a train in 1887 as it arrived in Plumerville and never seen again in Conway County. Local braggarts were reported to say that “he is feeding the catfish at the bottom of the Arkansas River,” but Trower was later found to have relocated to Independence County.

More closely associated with the Clayton assassination, George Earl Bentley of Morrilton (Conway County) was seen in the company of a Pinkerton private detective, Albert Wood, and was feared to be “turning” with regard to the stolen ballot box. The next day, November 27, 1888, Oliver T. Bentley, a deputy sheriff (and chief suspect in the ballot box theft), killed his brother George by “accidentally shooting him five times.” Federal, state, and local authorities investigated many murders like this one, but no charges were brought.

The Pinkerton Agency, employed by the Clayton family, expanded its investigation, and one of their local hires, a black man named Joseph W. Smith, was, on March 30, 1889, accosted by three men and shot and killed one mile north of Plumerville. With that incident, the Pinkerton investigation was brought to an end, and the agency left the area. The violence continued as an official of the state Republican Party was mauled and caned at the railroad depot when he arrived in Morrilton. He boarded the next train and never returned. Almost comically, a federal election official, Charles Wahl, had moved his family to Plumerville to follow leads and “set the investigation on the right path.” During a December 16, 1889, poker game in the office of Plumerville dentist Dr. Benjamin White, an attempt to kill him failed by less than an inch as the bullet tore through his ear. He quickly left the area, and the only charges brought were brought against him for gambling. He paid a nominal fine by mail, sent for his family, and never returned to Conway County.

In 1890, the federal election drew national attention, and mounted riflemen from the old Williams militia in Center Ridge came to Plumerville to ensure a fair election. More than 100 Winchester rifles had been delivered to Plumerville reportedly for the use of the African-American population. Armed militiamen marched “two by two” into town as the voting ended. Ballot boxes were protected, and the Republican candidate, Isom P. Langley, carried Conway County. Statewide totals, however, went to the Democrats, and their full control of statewide politics was firmly established for decades to come.

The racial oppression and the dire circumstances faced by many black families prompted much interest in the “Back-to-Africa” movement, emigration to the Republic of Liberia in western Africa. More than 1,500 people from south Conway County made application to the American Colonization Society for relocation. It is thought that almost one in five black families in Conway County made the application. From 1890 to 1892, more applications for Liberia were made in Arkansas than any other state, and more from Conway County than any other county in Arkansas.

While many areas of the South and in Arkansas created systems to block black voters, Conway County organizations later realized the opportunity to involve and bring minority voters into the process in the early 1900s. Predominately black precincts were established in several locations within the county, and candidates continue to work in these areas to provide a significant voting bloc in county elections. The bitterness between the white factions of the county, including pockets of Republicans from the old Williams affiliations around Center Ridge and Cleveland (Conway County) has also continued to a limited extent, reflected in quorum court sessions and county elections.

For additional information:

Barnes, Kenneth C. “Who Killed John M. Clayton?” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 52 (Winter 1993): 371–403.

———. Who Killed John M. Clayton? Political Violence and the Emergence of the New South, 1861–1893. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998.

Conway County Historical Society. Conway County-Our Land, Our Home, Our People. Little Rock: Historical Publications of Arkansas, 1989.

Historical Reminiscences and Biographical Memories of Conway County, Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas Historical Publishing Company, 1890.

Larry Taylor

Springfield, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.