calsfoundation@cals.org

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

In the years that followed Reconstruction, Arkansas experienced changes that paralleled trends taking place elsewhere in the nation. Nationally, the creation of the mass market and the economic growth that followed gave the era its basic character. The economy, and particularly the rise of industry, produced great prosperity for some whose spending habits gave the period its name—the Gilded Age. These developments also encouraged the movement of many people from the countryside to the city, producing a cultural and social transformation. But all of this came at a cost. Changes disrupted traditional economies and society, and many, particularly farmers and workers, failed to share in the bounty of the new world. In a state with an economy still largely agricultural, this meant that many in the state were mired in poverty. For others, especially those living in mountain isolation, older patterns of life prevailed. Conditions in Arkansas inevitably reflected national changes, but the state’s unique conditions colored how national trends affected its people.

Transportation and Markets

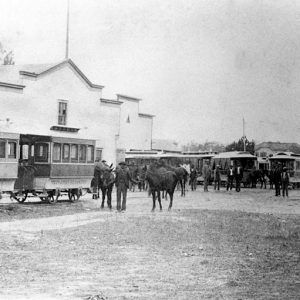

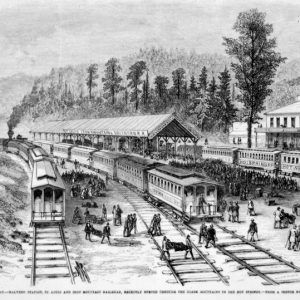

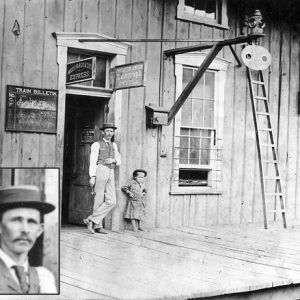

The rapid expansion of railroads following the Civil War provided the single most important force for change in the nation and in Arkansas during the Gilded Age. The state’s Republican government and its pro-railroad policies played a major role in local railroad construction. When the Civil War ended, only a few miles of track had been put into service between Little Rock (Pulaski County) and DeValls Bluff (Prairie County). By the end of Reconstruction in 1875, rails connected the capital city to Memphis, Tennessee, on the Memphis and Little Rock; to St. Louis, Missouri, and Texarkana (Miller County) over the Iron Mountain (the future Missouri Pacific); and to Van Buren (Crawford County) on the Fort Smith and Little Rock. In the years that followed, other railroads such as the St. Louis and Southwestern (or Cotton Belt), the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (or Frisco), and the Kansas City Southern tied most of the state’s major towns and agricultural regions into the national rail network. Additional branch lines constructed during these years brought even the most isolated parts of the state into this system. By 1895, railroad companies had completed 2,373 miles of track.

The railroads tied Arkansans into the broader national market, producing far-ranging results. Transportation costs dropped, flooding Arkansas with new products manufactured by the new industrial system. Everything from processed food to furniture appeared in Arkansas stores and households. Those who could afford these goods experienced a world of material comfort unknown to any but the rich in antebellum society. At the same time, the railroads made it possible for Arkansans to ship locally produced materials out of the state more easily, advancing new economic opportunities. Commerce and finance also shifted into new avenues, with St. Louis and Memphis challenging New Orleans, Louisiana, to be considered the state’s primary market.

New opportunities for making money emerged. The railroad companies, seeking to increase the amount of traffic they carried, actively promoted economic diversification in agriculture themselves. Companies encouraged people to come to Arkansas from the Midwest to develop lands in the Grand Prairie to be used for forage crops, such as hay, rather than for cotton. Many of the new farmers were from Europe and included Bohemians, Germans, Russians, Poles, and Slovaks. The communities that they settled, such as Stuttgart (Arkansas County) and Slovaktown (Prairie County), reflected their national origins. The railroad companies also promoted fruit growing and even established experimental farms where local farmers could learn how to cultivate new crops. By 1900, northwestern Arkansas had become a center for strawberry and apple production in the state, but farmers experimented with growing fruit almost everywhere the railroads went.

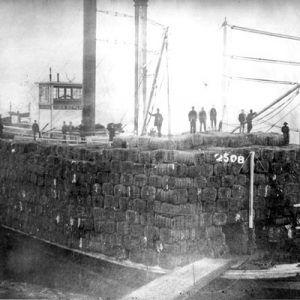

Expanded transportation facilities encouraged the spread of cotton farming. Cotton had been the state’s principal crop since the antebellum period, but the lack of a good way to get it to market had restricted its development to areas with ready access to river shipping. The spread of the railroads solved that problem and opened up arable land almost everywhere to the cultivation of cotton. As a result, farmers moved into previously undeveloped lands. At the same time, falling retail prices reduced the need for farmers to grow food for themselves and their animals, making it possible for them to devote a larger proportion of their land to cotton. Between 1879 and 1899, farmers expanded their improved lands from three and a half million to seven million acres. At the same time, the proportion of that land devoted to cotton grew from twenty-nine to fifty-seven percent.

The revolution in transportation also created opportunities for the exploitation of many of the state’s natural resources. Arkansas possessed extensive virgin forests, and a timber industry had emerged even before the Civil War. With the advent of the railroad, timber companies, many based in the Midwest, moved into the state and developed this particularly lucrative resource. Operations centered primarily on southern Arkansas during these years. A typical timber company, such as Colonel Samuel Fordyce’s Southern Land and Lumber Company, not only harvested trees but also operated mills to dress the raw timber. Between 1879 and 1889, the number of companies engaged in the cutting and processing of timber grew from 319 to 1,199. In this same period, the value of their goods increased from about $1 million to $24 million. By the end of the century, the timber industry accounted for more than twenty-two percent of the value of the state’s total economic product.

Another resource opened to development was coal. Arkansas possessed significant coal deposits, but their location in the western part of the state and the absence of an easy way to get the product to market meant that the coal fields had not been developed. Railroads solved the shipping problem. When the rails reached the Arkansas River Valley, entrepreneurs followed quickly to open up the coal fields. In 1880, the state produced only 14,778 tons hard coal. By 1900, mines shipped approximately two million tons. Coal mining never became a major part of the state’s overall economy, but the industry became a major economic activity in counties with significant deposits, such as Pope, Crawford, Franklin, Johnson, Logan, Sebastian, and Scott counties. Like the farms on the Grand Prairie, the western mines attracted European workers.

The railroads also made possible the exploitation of another of the state’s natural resources, its scenery and its mineral springs. Railroad construction into the Ozarks made possible the development of Eureka Springs (Carroll County). A rail connection into Hot Springs (Garland County) created a boom in that city. Other communities that possessed mineral springs, including Ravenden Springs (Randolph County) and Siloam Springs (Benton County), also became destinations for those seeking cures or relaxation.

Farming, Industry, and Economics

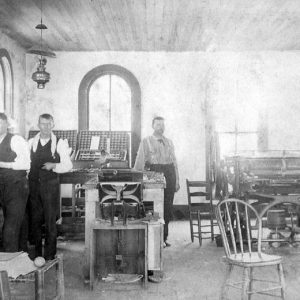

New crops, the spread of commercial agriculture, the timber industry, mining, and the railroads encouraged the growth of manufacturing within the state. Many new industries emerged to process the state’s farm goods. In the northwestern section, companies such as Springdale Canning and the Fayetteville Evaporator Company processed the new crops of apples, peaches, strawberries, and many different vegetables. In the cotton growing regions, new enterprises such as Southern Cotton Oil, Emma Oil of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), and the Little Rock Oil and Compress Company extracted cottonseed oil used for everything from the manufacture of soap to lubricants. The timber industry spawned companies such as Bluff City Lumber that produced window frames and other housing materials, Buddenberg Furniture Factory of Fort Smith (Sebastian County), and others that manufactured broom handles, oars, rifle stocks, and even golf clubs. Pine Bluff Agricultural Works, Pine Bluff Iron and Engine Works, and Little Rock Foundry and Machine Shops typified companies that fabricated plows, cotton gins, and a wide variety of other such equipment for the farm and the new industries. The railroad companies developed some of the most technologically advanced facilities. The Division Shops of the Cotton Belt at Pine Bluff and the Baring Cross Shops of the Iron Mountain at Little Rock built a variety of equipment for the railroads, including steam engines. These new concerns did not measure up to the factories of the Northeastern states in size or value, but their growth paralleled that of companies in many of the Midwestern states. Between 1879 and 1898, the value of the state’s manufactured products expanded from $6,756,159 to $45,197,731.

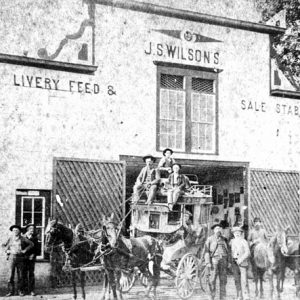

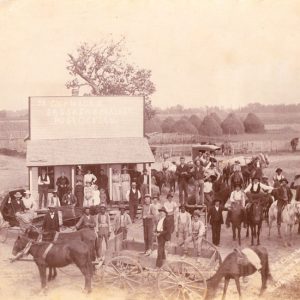

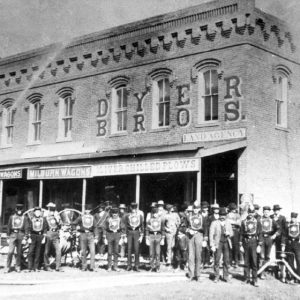

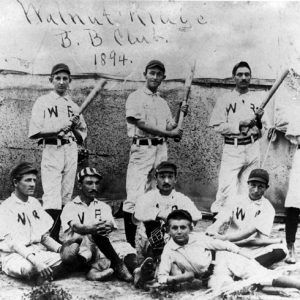

Farm expansion, resource development, and manufacturing brought a wide variety of other economic endeavors. Businesses and professions that offered necessary services flourished. Men flocked to towns to attend to local commerce. Wholesale merchants, cotton brokers, insurance agents and others attended to the flow of goods in and out of communities. Hotel owners, restaurateurs, and barbers offered services to those on the move. One of the most significant businesses to emerge in this period was banking, with McIlroy’s Bank in Fayetteville (Washington County), Pine Bluff’s Merchants’ & Planters’ Bank, and Little Rock’s W. B. Worthen & Company and the First National Bank being among the more successful. Entertainment also flourished, including theaters, saloons, and, not usually advertised by the town fathers, red-light districts. Accountants and engineers became essential components of the new economy. Even professionals such as doctors and lawyers found greater opportunities with the expansion of the market.

The state’s changing economy led to significant upheaval for the society and culture of Arkansans. Expanding economic activities produced new employment opportunities and began shifting the basic character of work in the state. In 1880, only seventeen percent of all workers in the state worked at jobs other than farming. Agriculture clearly dominated the labor market. By 1900, non-farm workers made up almost thirty percent of all workers. The move established a trend that continued unabated in the next century. The new jobs had an immediate impact on workers’ lifestyles. Wages got better. Even the average job in the timber industry, which offered the lowest wages of any of the new industries, provided an income three to four times what the typical farmer could expect. In terms of earning power, railroad workers were the elite of the new labor force, at least in part because many had joined unions such as the Knights of Labor in the 1870s and then the American Federation of Labor in the 1880s and 1890s. The new jobs gave workers new prosperity and a share of the material wealth being produced by the national economy.

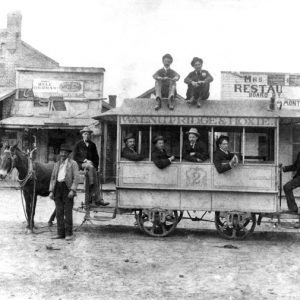

The state’s economy improved as Arkansas became more closely linked to the national market, but economic change also led to demographic change. Towns and cities became more important. The railroads actually created some new towns, such as Malvern (Hot Spring County), Texarkana, Hoxie (Lawrence County), Paragould (Greene County), and Wynne (Cross County). Older communities along the new transportation routes became the centers for many of the activities of the new economy. Little Rock, already an administrative and commercial center, grew almost 200 percent between 1880 and 1900, expanding from 13,138 to 38,307. Pine Bluff showed similar growth, reaching a population of 11,496 by 1900. Fort Smith, long avenue into the Indian Territory and home of Judge Isaac Parker’s for that area, attracted its share of new industries and, by 1900, had become the state’s second largest city with a population of 11,587. Smaller trade centers also boomed. Paragould, which was not established until 1883, reached a population of 3,324 by 1900 and was the state’s eleventh largest city. In 1880, only four percent of the state’s population was considered to be urban. By 1900, the number had more than doubled. Living together in larger communities forced rural Arkansans to integrate themselves into a more complex social order. They confronted religious, ethnic, and occupational diversity. They also encountered, to a much greater degree than those left behind down on the farm, the broader national culture.

The economic transformation taking place created prosperity and new lifestyles for some, but in a state still dominated by farming, these changes also had a widespread negative impact. Crop diversification and the greater focus on cotton as a cash crop offered some potential for farmers to get ahead, but other forces worked against that success. The expanding national market gave Arkansans more places to sell their goods, but it also forced local products into increasing competition with farmers elsewhere in the country and overseas. Conditions for the cotton grower typified those for every other farmer in the state. Productivity simply outpaced consumption. As a result, the prices of all farm products declined steadily in the three decades of the Gilded Age. Cotton prices led the way down and had the greatest impact on Arkansas farmers because of the crop’s local importance. Average prices of about twelve cents per pound in the mid-1870s fell as low as six cents per pound by 1898. Few farmers made much money on cotton at that price. Wheat growers in the northwest part of the state confronted competition from inexpensive flour produced in the Midwest, and even the skilled craftsmen of the towns struggled to survive as mass-produced industrial goods entered the market from the North.

The collapse of prices produced hard times, but steadily declining productivity among Arkansas farmers worsened the situation. The size of farms decreased throughout this period, which created less efficient operations. From 1879 to 1899, the average size of a farm in the state fell from 128 acres to ninety-three acres. At the same time, many of these farms developed on marginal lands. Farmers who worked these small units seldom had the resources to cultivate the land efficiently. Mule-drawn plows that could not cut deeply into the earth, a lack of money to buy fertilizers, and the inability to improve land through crop rotation—all of this led to diminishing crops. As a result, the output per acre diminished each year. Between 1879 and 1899, the state’s cotton crop output again led the way, dropping from 0.6 to 0.4 bales per acre.

Conditions pushed many farm families into poverty. They fought to survive while paying off loans to country merchants and bankers. In many cases, the struggle ended in bankruptcy. This caused a significant shift in the character of farming in many parts of the state. As farm owners defaulted on their loans and found their property seized by creditors, land ownership shifted into the hands of corporate owners, especially merchants and banks. Tenant farming became increasingly important, with tenants often working as sharecroppers, receiving a portion of the crop for their work while the actual landowner received another portion for the use of the land. This system had emerged after the Civil War as the primary way landowners contracted with freedmen for their labor, but the practice expanded between 1879 and 1898 with large numbers of white farmers joining African Americans as tenants. During these years, the number of farms operated by tenants increased from thirty-one to forty-five percent, a statistic that indicated not only the changing nature of farm tenure but also pointed to the destitution of many farm families.

Politics, State Finances, and Protest Movements

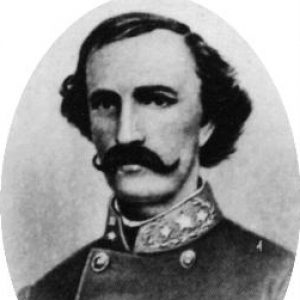

These contrasting economic and social trends played a major role in determining the character of state politics during the Gilded Age. Throughout this period, the Democratic Party dominated the state’s political life and controlled most state and local government. The assumption of power by Augustus Hill Garland as governor in 1874, bringing an end to the unrest of Reconstruction, marked the beginning of the new era. Garland typified the men who held the office for the next twenty-six years. He had been a Unionist before the war and a member of the Secession Convention in 1861 but had then gone on to serve in the Confederate Congress and become a fervent supporter of the Confederacy. Garland secured power in part because of his stand during the Civil War and his opposition to Republican state government during Reconstruction. Most of his successors played upon the same issues in reaching the governorship. William Read Miller, Confederate state auditor, followed Garland as governor in 1877 and served until 1881. Confederate General Thomas James Churchill became governor in 1881, Confederate veteran and amputee James Henderson Berry in 1883, Lieutenant Colonel Simon P. Hughes in 1885, and Lieutenant Colonel James Philip Eagle in 1889. William Meade Fishback ended this run of former Confederate officials in 1893. Fishback had been a wartime Unionist and a Republican, but he had become a Democrat and proved particularly popular among voters because of his desire to repudiate much of the state’s debt.

The state’s debt and state finances were a central issue in much of post-Reconstruction politics. The state debt had reached seventeen million dollars by 1875. Simply paying the annual interest on notes had given the government little discretionary money. This debt consisted of a variety of obligations, including levee and railroad bonds issued during Reconstruction. Among these were the Holford Bonds, state obligations sold to fund the outstanding debts of the state’s prewar Real Estate Bank. At the same time that interest payments consumed much of its budget, other financial needs of the state had increased considerably. Partly because of neglect during the 1860s, state institutions such as the penitentiary and schools for the blind and deaf needed repairs. The state had to fund the public schools and colleges created during Reconstruction. Increasing competition with other states for investment capital required new agencies—such as the state’s bureau of statistics and bureau of agriculture, mining, and manufacturing—to advertise the state’s natural resources and economic advantages to encourage individuals, companies, and investors to come to the state.

Solving these fiscal problems was difficult because of the state’s economy and the basic socioeconomic character of the community. The surest way of handling the state’s financial problems was to raise taxes. The difficulty for the government, however, was that the primary sources of tax revenues in this period were taxes on real estate and personal, and land taxes provided the largest part of the revenue raised from this source. This meant that the primary means of increasing revenue would be to raise taxes on the most powerful element within the state—its landowners. Taxation on other economic activities was possible, but some of these, such as manufacturing, were in their infancy, and raising taxes on them would be counterproductive to the goal of diversification. The state’s debt might be eased, but that would also create problems by ruining the state government’s credit.

Governmental response to these problems showed the character of political power in the state. Politicians generally protected large landed interests, passing laws that kept tax rates low, despite pressing needs, and placing the assessment of taxes in the hands of county officials, practically guaranteeing the under-assessment of property values. Repeated efforts at increasing taxes and changing the assessment system failed. Large landowners’ power also could be seen in legislation on labor issues. Generally, new statutes passed through these years strengthened the power of landowners over their tenants, the most important measure being to give the landowner the first lien over a tenant’s crop. At the same time, the legislature did nothing to protect the tenant against the all-too-common predatory practices of landowners and merchants.

The same leaders wanted the state to be a part of the national prosperity at the time, but that required spending for education and new agencies. On the other hand, they tried to make operations as inexpensive as possible. In the case of the state’s prison, leaders tried to fund it by making it self-supporting. Private contractors leased prisoners (called the convict-lease system), and the income from the leases went to pay for the expenses of the prison. Conditions for these prisoners became so bad that the state considered ending the lease system, although plans for its replacement would have put the prisoners to work for the state rather than for outside contractors. The legislature provided minimal funds for education and left support for schools primarily to local school districts. The Black population was particularly victimized by policies to keep costs down. Even though they constituted twenty-eight percent of the overall population of Arkansas in 1900, Black citizens received less money per capita for state services than whites. Officials kept costs low by providing them with second-class or no schools and other cut-rate services.

Conservative Democratic governors and legislators managed to hold on to state government for twenty-five years, but these were not peaceful times. Economic problems encouraged considerable unrest among those who believed they had been dealt with unfairly, and the problems led to a variety of protest movements. The first significant threat to Democratic control came in the form of the Greenback Party in the late 1870s. An offshoot of the national Greenback Labor Party, the Arkansas Greenbackers, who believed that national monetary policy placed an undue burden on the debtor, sought to expand the national currency with paper money. The local Greenback Party backed the national party’s monetary policies but also became the first organization to criticize the directions taken by local Democratic leaders. The Greenbackers ran W. P. Parks against Governor Churchill in 1880 and received twenty-seven percent of the vote as a result of fusion with the state Republicans. This set the tone for protest politics. Whenever a third party could link with the Republicans, as in 1880, they made a serious challenge to the Democrats. When Republicans ran their own candidates, the dissidents had more trouble. The election of 1882 was typical of the latter. Greenback candidate Rufus Garland managed to receive only seven percent of the vote against James H. Berry after the Greenbackers failed to agree on a fusion candidate with the Republicans.

Other opposition movements emerged following the collapse of the Greenback Party in the early 1880s, the best known being the Agricultural Wheel and the Brothers of Freedom. These groups emerged primarily from among the increasingly dissatisfied farmers of this period who wanted government to redress their growing problems. These men embraced an agrarian program that urged the state government to take a greater role in the regulation of corporations. They wanted regulation of railroads, including control over passenger and freight rates. They also believed that railroads, financial institutions, expanding telegraph companies, and other such businesses were under-taxed. While sometimes appearing to accede to these agrarian demands, the legislature proved as attentive to corporate interests as to those of large landowners and generally gave the protestors little. It created a state railroad commission in 1883, for example, but gave it virtually no power to impose any of the desired regulations or to enforce those that existed. Such failures encouraged an increasing involvement of the protest groups in politics.

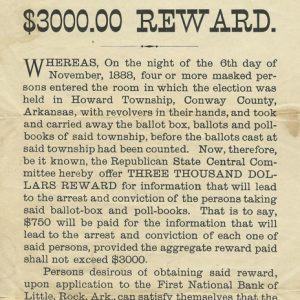

In 1884, Agricultural Wheel members attempted to nominate one of their supporters as the Democratic Party’s nominee for governor but failed. The next year, the Wheel and Brothers of Freedom united to organize the Agricultural Wheel to advance an agrarian agenda. At the same time, they reached out for support among the state’s workers. In the 1886 gubernatorial election, the Wheel candidate, Charles E. Cunningham, received only twelve percent of the vote, but Charles M. Norwood, Union Labor’s candidate in 1888, showed wider appeal. After years of being firmly in control of government, the Democratic leadership faced a real challenge from Norwood and did all it could to defeat him, resorting to intimidation and fraud to ensure the continuation of their power. Even under these conditions, Norwood received forty-six percent of the 183,427 votes counted in the formal tally. Citing fraud in twenty-seven counties, including the stealing of ballot boxes, Norwood claimed that he had won and appealed the results. Later scholars have concluded that Norwood may have won, but the Arkansas General Assembly stymied his efforts to obtain a full investigation of his charges. In the election of 1890, Napoleon B. Fizer ran as the candidate against the incumbent, James P. Eagle, and received more votes than Norwood. But the increased turnout of 191,448 voters saw the party’s actual portion of the total reduced to forty-four percent. Still, Union Labor had become a serious threat to Democratic power at the state level and successfully carried some county elections.

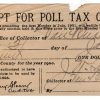

Rather than risk defeat, the legislature moved to reduce the agrarian threat by disfranchising many supporters of the movement. The legislature significantly changed the character of the state’s electoral process with an election law passed in 1891. The most important provision of that law was to require illiterate voters to have their ballots marked by election judges. Critics contended that it was designed to intimidate poor white and Black voters who could not read and write into not voting. The law achieved that result, reducing in particular large numbers of Black voters who had provided the support that allowed fusion candidates to challenge Democratic control. Even though the 1892 gubernatorial campaign saw another vigorous contest, this time between the Democratic candidate, William M. Fishback, and the newly organized Populist Party’s candidate, Jacob P. Carnahan, the number who went to the polls declined eighteen percent to only 158,876 voters. Fishback easily won the governorship. The 1892 election effectively ended third-party protest in Arkansas. Voter participation in the state’s elections steadily declined thereafter. That election also marked the virtual disappearance of Black politicians from state government until the 1960s. In 1891, the General Assembly still had eleven Black members. In 1893, there were none. The General Assembly pushed for additional constraints on Black voting after this. Its members placed an amendment creating a poll tax on the ballot in 1892, and it passed. The creation of a system of party primaries in the 1890s for practical purposes further disfranchised Black voters, most of whom were Republicans. By the turn of the century, the Democratic primary decided who would win the general election, and Black voters made little impact in the choice.

Race Relations and Segregation

Supporters of the election law took advantage of another important characteristic distinguishing this era. In Arkansas, as well as throughout the rest of the South, race relations were altered as a result of broader social changes. Most whites had continued to treat African Americans as inferiors following the end of slavery, and the races lived in informally segregated worlds. Still, as free people, Black citizens had secured political and civil rights along with opportunities to improve themselves. In towns, the rise of a Black middle class presented an increasing challenge to existing relationships. Wiley Jones of Pine Bluff, John E. Bush, founder of the Mosaic Templars of America, and Mifflin W. Gibbs, prominent Little Rock attorney, all represented this prosperous class. Even in the countryside, some Black farmers such as Scott Bond of Madison (St. Francis County) and Pickens Black of Jackson County achieved financial success, as did an entire community of Black landholders at Menifee (Conway County). By the 1880s, such men were able to pay for better accommodations on the state’s railroads and in hotels, theaters, and other public venues, and they wanted equal access. In the countryside, Black workers continued to protest unfair treatment, including participating in the various farm movements that challenged Democratic rule.

Frequently, whites reacted to Black aspirations with violence; this could include lynching, nightriding (a.k.a. whitecapping), racial cleansing (creating what are called “sundown towns“), or large-scale race riots. In rural areas, they tried to drive African Americans off of their land. In the towns and cities, whites responded with an increasing demand for a more formal separation of the races and the exclusion of Black citizens from whites’ facilities. Contemporary development of scientific theories of inherent racial differences provided support for their arguments, and by the middle of the 1880s, Arkansas’s white newspapers increasingly referred to African Americans as racially inferior and demanded formal segregation.

Racist arguments helped secure passage of the 1891 election law, but they also set up the creation of laws systematically separating the races. In 1890, the Democratic candidate for governor, James P. Eagle, campaigned on a promise not only to change the election laws but also to support laws requiring railroads to provide separate coaches for Black passengers. The popularity of the issue among whites was clear. Eagle won, and in February 1891, the legislature passed a “Separate Coach” law. This was only the first of numerous measures that formally segregated the races in all public spaces. Leaders in the Black community protested these efforts, but because they were excluded from political power by changing election laws, their voices remained largely unheard in the rush to create a segregated society during these years. These measures established the character of race relations in the state until the middle of the next century.

Toward the Twentieth Century

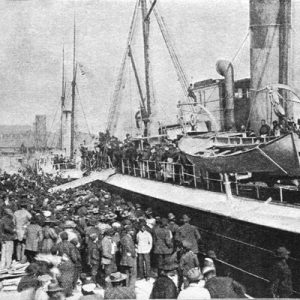

Arkansans ended the nineteenth century in a world that differed from that existing at the end of Reconstruction. A major symbol of the state’s integration into the wider nation was its participation in the Spanish-American War, with two regiments of Arkansas troops in the service of the United States. The war marked a final reconciliation of not only Arkansas but all of the former Confederate states with their northern neighbors as (white) Southern and Northern boys fought together again. At the same time, the changes of this era brought about by closer ties with the rest of the country produced their own unique results for Arkansas. Prosperity increased for some people, but at the same time, the new economy added to the grinding poverty of the farm. Urbanites participated to a much greater degree in the success and culture of the nation, yet during the same period, those in the countryside found themselves left behind. Race relations worsened as whites moved toward the creation of a segregated society. By 1900, the economic and social differences that set apart economic regions from each other, town dwellers from those in the countryside, and African Americans from whites were well-established and would dominate the life of Arkansas for years to come.

For additional information:

Barjenbruch, Judith. “The Greenback Political Movement: An Arkansas View.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 36 (Summer 1977): 107–22.

Dillard, Tom. “Golden Prospects and Fraternal Amenities: Mifflin W. Gibbs Arkansas Years.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 35 (Winter 1976): 307–33.

———. “To the Back of the Elephant: Racial Conflict in the Arkansas Republican Party.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 33 (Spring 1974): 3–15.

Elkins, F. Clark. “The Agricultural Wheel: County Politics and Consolidation, 1884–1885.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Summer 1970): 152–75.

———. “Arkansas Farmers Organize for Action: 1882–1884.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 13 (Autumn 1954): 231–48.

Elman, Cheryl, Barbara Wittman, Kathryn M. Feltey, Corey Stevens, and Molly Hartsough. “Women in Frontier Arkansas: Settlement in a Post-Reconstruction Racial State.” Du Bois Review 16 (Fall 2019): 575–612.

Giggie, John M. After Redemption: Jim Crow and The Transformation of African American Religion in the Delta, 1875–1915. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Gordon, Fon Louise. Caste & Class: The Black Experience in Arkansas, 1880–1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995.

Graves, John William. “The Arkansas Separate Coach Law of 1891.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Summer 1973): 148–65.

———. “Negro Disfranchisement in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 26 (Autumn 1967): 199–225.

———. Town and Country: Race Relations in an Urban-Rural Context, Arkansas, 1865–1905. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Hild, Matthew. Arkansas’s Gilded Age: The Rise, Decline, and Legacy of Populism and Working-Class Protest. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2018.

Holmes, William F. “The Arkansas Cotton Pickers Strike of 1891 and the Demise of the Colored Farmers’ Alliance.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Summer 1973): 107–19.

Matkin-Rawn, Story. “‘The Great Negro State of the Country’: Arkansas’s Reconstruction and the Other Great Migration.”Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Spring 2013): 1–41.

Miller, John E. “Isaac Charles Parker.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 31 (Spring 1972): 57–74.

Moneyhon, Carl H. Arkansas and the New South, 1874–1929. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

———. “Black Politics in Arkansas During the Gilded Age, 1875–1900.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 44 (Autumn 1985): 222–45.

———. “The Creators of the New South in Arkansas: Industrial Boosterism, 1875–1885.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 55 (Winter 1996): 383–409.

Paisley, Clifton. “The Political Wheelers and Arkansas’s Election of 1888.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 25 (Spring 1966): 3–21.

Rogers, William W. “Arkansas Labor in Revolt: Little Rock and the Great Southwestern Strike.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 24 (Spring 1965): 29–46.

Smith, Kennth L. Sawmill: The Story of Cutting the Last Great Forest East of the Rockies. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

Carl H. Moneyhon

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.