calsfoundation@cals.org

New Deal

In many ways, Arkansas experienced the hardship of the Great Depression of the 1930s even before the stock market crash of 1929. In the 1920s, it led the nation in per capita indebtedness. As an agricultural state, Arkansans was affected by low crop prices, which left people unable to pay taxes. Schools and roads deteriorated. Without funding for road construction, some towns found themselves isolated and cut off from the rest of the state. Arkansas also suffered as it alternated between both drought and floods—the Flood of 1927, followed by the Drought of 1930–1931 and the Flood of 1937. Banks failed, wiping out savings and ready cash. Many Arkansans lost their land, being forced to become tenant farmers. Others could not even subsist that way. Tent cities and shantytowns often called “Hoovervilles” after the president at the time of the crash, Republican Herbert Hoover, sprang up around the state, including a camp for the homeless outside Forrest City (St. Francis County). Rural areas of Arkansas were not alone in the hard times. Even the state’s capital city of Little Rock (Pulaski County) was struggling with unemployment. Though Hoover did, later in his presidency, begin working on programs to help alleviate the Great Depression, his successor, Democrat Franklin Roosevelt, elected president in 1932, put together a more comprehensive plan to overcome the collective hardships, a plan he called “a New Deal for the American people.” The people of Arkansas were among the millions who benefited.

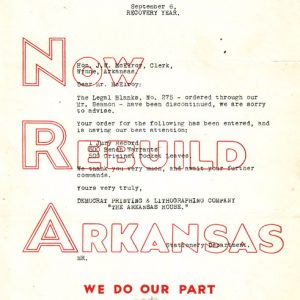

In the first 100 days of the Roosevelt administration, banks were stabilized, foreclosures were slowed, jobs were created, and relief programs were put in place by New Deal legislation. Much of the momentum came from the New Deal’s so-called alphabet soup agencies. These included the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), National Recovery Administration (NRA), National Youth Administration (NYA), Public Works Administration (PWA), and Works Progress/Projects Administration (WPA).

An important reason Arkansas got its share of New Deal programs was due to the state’s two U.S. senators, both Democrats: Hattie Wyatt Caraway (1878–1950) and Joseph Taylor Robinson (1872–1937). Both served Arkansas in the Senate during the Great Depression (Caraway from 1932 to 1944, and Robinson from 1913 until his death in 1937). Both were strong supporters of the New Deal and worked to bring relief programs to Arkansas. Caraway especially concentrated on farm relief, flood control, and constituent services. A well-known saying in Arkansas at the time was, “Write Mrs. Caraway—she will help you if she can.” Beginning in 1932, Robinson was majority leader of the Senate, where he ensured passage of FDR’s New Deal legislation. To celebrate the state’s centennial, which Caraway had helped to plan, President Roosevelt came to Arkansas on June 10, 1936, marking the first time a sitting president had visited the state. At that time, FDR publicly acknowledged Robinson’s many vital contributions, afterward going to Robinson’s Little Rock home for a private dinner.

The CCC put more than 200,000 young Arkansas men to work across the nation—many in one of the seventy-seven companies within the state. The men performed more than 100 types of jobs such as building parks, developing hiking trails, planting trees, and saving millions of acres of farmland from soil erosion. Many CCC projects in Arkansas are still enjoyed today, such as the Crowley’s Ridge, Devil’s Den, Mount Nebo, and Petit Jean state parks.

The NYA enlisted young women and men ages sixteen to twenty-five in various programs such as construction projects for the young men, and service projects, homemaking, and crafts projects for young women. Arkansas NYA projects included construction or repair of school facilities such as shop buildings, vocational agriculture structures, home economics cottages, and gymnasiums.

When WPA programs came to Arkansas in 1935, William Reynolds Dyess (1894–1936) was appointed the WPA’s first state administrator. After his death, the Dyess (Mississippi County) colony, a New Deal relocation program in northeastern Arkansas for displaced farmers, was named for him. The Dyess colony and the state of Arkansas received positive national publicity on June 11, 1936, in First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s newspaper column, “My Day.” She wrote, “My first glimpse of Arkansas was a drive through very rich country just before sundown on my way to the Dyess Colony.” For a state used to being ridiculed as a poor backwater, it was good press.

For other Arkansas projects, the WPA employed rural laborers in building bridges, courthouses, dams, farm-to-market roads, parks, rural schools, and recreational facilities such as band shells (like the Women’s Community Club Band Shell) and swimming pools. The New Deal also provided resources for public buildings in Arkansas, including the Joseph Taylor Robinson Memorial Auditorium in Little Rock, which was dedicated in 1940 to honor the late senator.

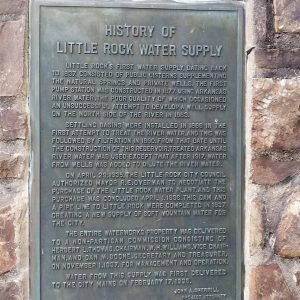

Other New Deal projects in Arkansas include the water tower in Green Forest (Carroll County) and the community center in Jonesboro (Craighead County). Known as the Earl Bell Center, it continues to serve the people of the Jonesboro community. New Deal projects such as the Camp Ouachita Girl Scout Camp Historic District at Lake Sylvia in Perry County, the Haggard Ford Swinging Bridge near Harrison (Boone County), and the Miller County Courthouse in Texarkana (Miller County) are still in use in the twenty-first century.

The Russellville Public Library was a joint effort of the WPA and the people of Russellville (Pope County). The building was used by the community from 1936 until 1976, when a larger library was built next door.

New Deal agencies provided opportunities for women, and, in 1935, Arkansas became the first southern state to fill all its WPA slots for women. In DeWitt (Arkansas County), Harrison, Malvern (Hot Spring County), and Paragould (Greene County), female WPA workers made clothing in sewing projects, served hot lunches to school children, taught adult education classes, and tended to the sick in household aid programs. Arkansas also housed one of only five NYA camps for young Black women, where arts classes and vocational training were offered.

The New Deal’s Federal Writers’ Project employed educators, historians, writers, and other professionals to research and write what were often the first comprehensive travel guides for each state. Arkansas: A Guide to the State was researched during the Depression and published in 1941. For many people across the nation, it was their first glimpse of Arkansas. The WPA also sponsored interviews with African Americans who were former slaves. In writing and recording their narratives, it served as a first look for many Americans into a part of American history they knew little about.

Likewise, the Treasury Department’s Section on Fine Art sponsored murals and sculptures created by unemployed artists in various post offices and other buildings. Many of them remain, including murals at the post offices in Clarksville (Johnson County), Dardanelle (Yell County), Heber Springs (Cleburne County), Lake Village (Chicot County), Morrilton (Conway County), Nashville (Howard County), Paris (Logan County), and Piggott (Clay County).

The Living New Deal website lists more than 160 buildings and other projects that still exist in Arkansas thanks to the New Deal. Along with much needed jobs and relief funds, New Deal programs in Arkansas often accomplished a great deal more: they gave the people of a state teetering on the edge of bankruptcy a sense of pride, hope, and self-respect.

For additional information:

“Arkansas Post Office Murals.” University of Central Arkansas. http://uca.edu/postofficemurals/home/ (accessed January 3, 2026).

Greene, Alison Collis. No Depression in Heaven: The Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Transformation of Religion in the Delta. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Hendricks, Nancy. Senator Hattie Caraway: An Arkansas Legacy. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2013.

———. Dear Mrs. Caraway, Dear Mr. Kays. Jonesboro, AR: Master Printing Company, 2010.

Hicks, Floyd W., and C. Roger Lambert. “Food for the Hungry: Federal Food Programs in Arkansas, 1933–1942.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 37 (Spring 1978): 23–43.

Holly, James Donald. “The New Deal and Farm Tenancy: Rural Resettlement in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi.” PhD diss., Louisiana State University, 1969. Online at https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1664/ (accessed January 3, 2026).

Miller, Rachel M. We Will Persevere! The New Deal in Arkansas: Students Learning from Local and Statewide Historic Places. Little Rock: Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, 2011.

“States and Cities: Arkansas.” The Living New Deal. https://livingnewdeal.org/us/ar/ (accessed January 3, 2026).

Nancy Hendricks

Garland County Historical Society

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.