calsfoundation@cals.org

Folk Music

Folk music is part of a society’s “unofficial culture,” much of which is passed on through face-to-face contact among close-knit people. Early folk music in Arkansas falls into two broad categories: folksongs (which do not present a narrative) and ballads (which tell a story). Folksong collectors sought to record and preserve this traditional music in the twentieth century, with Vance Randolph, John Quincy Wolf, and others working in Arkansas. The lyric folksong form of the blues developed in the Arkansas and Mississippi Delta regions in the late nineteenth century among the first generation of African Americans to come of age after slavery. Protest music of the early to mid-twentieth century, dealing with labor and social conditions—as well as war, civil rights, and politics—took on the folk style and sensibility, contributing to the renewed interest in traditional folk music, termed the folk revival, of the 1950s and 1960s. The mid-to-late twentieth century brought the contemporary/popular folk style into prominence, with the singer/songwriter at the forefront.

Because verbal folklore, including folk songs, circulates among individuals in oral interactions, it lacks the permanence that writing or other communicative media might produce. It is also variable, with each performance of a song evincing some distinctive elements, although some performance features—such as diction, style, and theme—remain relatively constant. (It is this unique nature of the traditionally performed folksongs that later folksong collectors sought to capture before modernizing forces caused these songs to be lost and forgotten as the singers who served as the keepers of the traditions died.)

Arkansas’s Image in the Folk Music Tradition

Early European and Euro-American impressions of Arkansas often drew upon folk traditions. Stories about the state’s remarkable fruitfulness, for example, incorporated elements from similar boasts in Europe: crops that would grow up overnight and produce gargantuan yields, game and fish both plentiful and compliant, and an environment so healthy that the very water had medicinal properties. When Arkansas failed to live up to its billing, negative folklore and folksongs developed that exaggerated its failings—again using traditional images and patterns. The song usually known as “The State of Arkansaw,” which probably dates from the 1890s, articulates the state’s anti-image that developed. The song’s narrator arrives in Arkansas full of hope that fortune awaits him. He is soon disabused of this illusion when an unkempt, unhealthy-looking Arkansawyer offers him a job draining swampland. After weeks of hard labor on mean rations, the narrator laments, “I never knew what misery was till I came to Arkansas.” In both positive and negative manifestations, however, Arkansas’s image is far from unique, as many geographic areas could not live up to settlers’ hopes for them. Similar negative images in American folksong have attached to the “dreary Black Hills” of the Dakotas, “Nebraska land,” and the abode of the “Lane County Bachelor.”

Blues and Gospel in the Folk Tradition

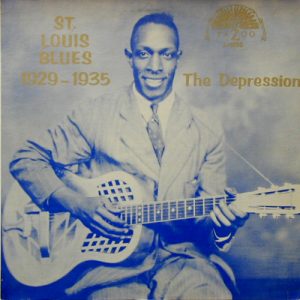

The blues may be the most widely known folklore form associated with the Arkansas flatlands. Influenced by the field hollers and worksongs that accompanied agricultural labor and by religious music—especially the gospel music that was emerging with it—the blues operates as a commentary on the everyday life of its performers and audience. Although its most frequent topic is the male-female relationship, the blues may deal with virtually any concern in the community. Commercial recording of the blues began in the 1920s, and performers associated with Arkansas such as Peetie Wheatstraw (William Bunch), who grew up in Cotton Plant (Woodruff County), and Big Bill Broonzy (William Lee Conley), who lived in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), were appearing on recordings within the next decade. Many traditional blues performers, though, were never recorded at all.

Religious music—including hymns from the late eighteenth century, slave spirituals, and gospel music performed by ensembles using four-part harmony or by charismatic soloists such as Rosetta Tharpe (also from Cotton Plant)—added to the folk music soundscape of the Arkansas Delta. Blues and gospel also contributed to the development of commercial rock and roll, many of whose pioneers, including Johnny Cash, Billy Lee Riley, and Sonny Burgess, were Arkansans.

Folk Music in the Ozarks

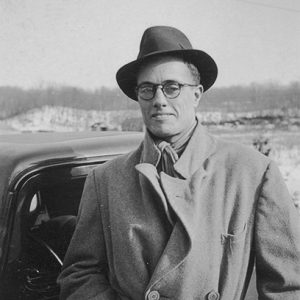

Folklorist Vance Randolph was attracted to the Ozarks—where he had vacationed as a child—by the appeal of ballads, particularly the narrative folksongs from England and Scotland that Harvard University professor Francis James Child had anthologized in the late nineteenth century and many of which dealt with knights and ladies in pseudo-medieval settings. Randolph—along with his wife, Mary Celestia Parler, who was a professor of English and folklore at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County)—was fascinated that Ozark “peasants” living in the early twentieth century as subsistence farmers in an isolated pocket of the United States were singing songs about British nobility and royalty that could be traced in a few cases to the late Middle Ages.

Ozark singers supplemented these old narrative folksongs from the British Isles (known as “Child ballads” for the Harvard professor who edited and numbered the collection) with more recent songs from Britain and Ireland; with indigenous ballads that told stories of Robin Hood-like outlaws, Civil War battles (including the Battle of Pea Ridge), railroad disasters, and other American themes; and with sacred and secular folk lyrics that did not tell stories but rather conveyed moods or emotions.

Randolph worked primarily in the western Ozarks and produced one of the most comprehensive collections of American folksongs from a single American region: the four-volume Ozark Folksongs, which the State Historical Society of Missouri published between 1946 and 1950. One of Randolph’s most gifted performers of folksongs was Emma Dusenbury, born in 1862, of Mena (Polk County), a traditional singer whose work is represented by some 116 songs in the nation’s leading folksong archive at the Library of Congress.

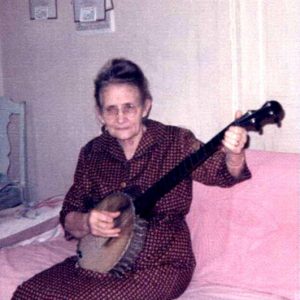

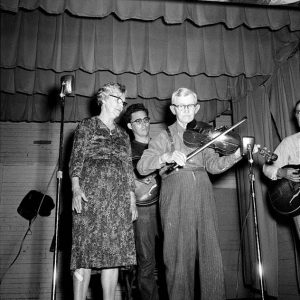

A generation later, John Quincy Wolf was collecting ballads and other folksongs in the eastern Ozarks. Wolf made contact with folk singer Almeda Riddle of Cleburne County, as well as the Morris family of Timbo (Stone County). James Morris—as Jimmy Driftwood—became a well-known songwriter and popularizer of Ozark folksongs in the 1950s and 1960s. Singer and banjo player Ollie Gilbert—born in Stone County in 1892—was recorded by Wolf as well as folksong collector Alan Lomax (son of John Lomax) around 1960. An early member of the Rackensack Folklore Society, she performed at folk festivals in Arkansas and in California and Washington DC.

Folksongs were the primary lure that drew early collectors to the Ozarks. Both Randolph and Wolf gathered substantial bodies of material and identified important performers of this material. Black folk music and instrumental music did not receive as much attention, however, although several Ozark string bands, featuring skilled fiddlers such as Absie Morrison, made recordings in the late 1920s.

Folk Revival in the Modern Era

Folk music in Arkansas has carried on into the modern era, with many Arkansas performers and songwriters continuing, preserving, and reviving the traditions, while adding their own contributions (often influenced by other styles such as blues, country, and rock) along the way.

While some consider the revival period of the mid-twentieth century to be a rediscovery of folk music, for some musicians, such as Almeda Riddle and others, the traditional music never went away in the first place. Discovered by ballad collector Wolf in the 1950s, Riddle of Cleburne County, born in 1898, became a prominent figure in America’s folk music revival. Her memory of ballads, hymns, and children’s songs was one of the largest single repertories documented by folksong scholars. Violet Brumley Hensley, a fiddle maker and musician born near Mount Ida (Montgomery County) in 1916, was designated as the 2004 Arkansas Living Treasure by the Arkansas Arts Council, which recognized Hensley as an outstanding Arkansan who actively preserves and advances the art form of fiddle-making. Hugh Ashley, who was born in 1915 near Wiley’s Cove (Searcy County), wrote and recorded some of the earliest known recordings of Ozark folk music, was one of radio’s original “Beverly Hill Billies,” and wrote songs for five members of the Country Music Hall of Fame.

As part of the protest music aspect of the American folk tradition, John L. Handcox, born in 1904 in Brinkley (Monroe County), became the voice of the common sharecropper through the poems and songs he wrote for the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU), a federation of tenant farmers formed in 1934 in Poinsett County. Handcox joined the STFU in 1935 and “found out singing was more inspiring than talking…to get the attention of the people.” Through Handcox’s recordings for the Library of Congress, folk greats Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger had discovered his songs by the 1940s, performing and recording them in subsequent years as labor protest songs. Handcox wrote protest songs into the Reagan era of the 1980s.

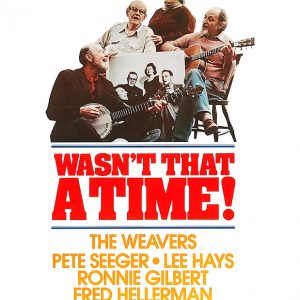

Paris (Logan County) native Zilphia Mae Johnson Horton, born in 1910, was an influential educator, folklorist, musician, and social justice activist who collected, adapted, performed, and promoted the use of folksongs and hymns in the labor and civil rights movements, notably protest anthems “We Shall Not Be Moved” and “We Shall Overcome.” Fellow protest/political musician Lee Hays, born in Little Rock in 1914, was one of the original members of the Almanac Singers—perhaps the first folksong popularizers to adopt a progressive political agenda—and is best known for singing bass with the folk revival group the Weavers. According to historian Studs Terkel, the Weavers were responsible for “entering folk music into the mainstream of American life.” Among the songs Hays is most known for are: “If I Had a Hammer,” “Roll the Union On,” “Raggedy, Raggedy, Are We,” “The Rankin Tree,” “On Top of Old Smoky,” “Kisses Sweeter than Wine,” and “Goodnight Irene.” Members of the Weavers who had been in the Almanac singers—Hays and Seeger—had politics that ran afoul of the McCarthy-era political climate, and they were blacklisted, with the Weavers disbanding in 1952 (although the group later reunited a few times).

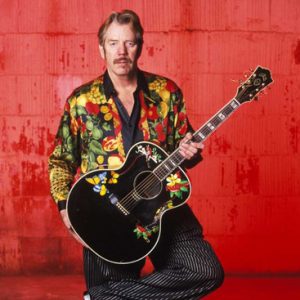

With the way paved for a modern-day folk singer offering up traditional songs and forms, Jimmy Driftwood of Stone County (whose father was also a folk singer) became a major figure in the folk revival scene of the 1950s and 1960s, writing more than 6,000 songs. He gained fame in 1959 when Johnny Horton recorded Driftwood’s song “The Battle of New Orleans.” Even after Driftwood had risen to fame on the national scene by the late 1950s, he continued living in rural Stone County where he was born, spending most of his time promoting and preserving the music and heritage of the Ozark Mountains.

Popular/Contemporary Folk Music of the 1960s and Beyond

The influence and merging of other musical styles such as country, blues, jazz, and rock is especially seen in the popular/contemporary folk genre that emerged in the 1960s, with the singer/songwriter serving as a central figure. Dan Hicks, born in Little Rock in 1941, was a cross-genre singer/songwriter specializing in a type of music he called “folk jazz.” He served as front man for his band, the Hot Licks, which performed off and on starting in 1968. Hicks died in 2016. Iris DeMent, born in Paragould (Greene County) in 1961, is a singer/songwriter from Arkansas. She has lent her distinctive voice to folk, country, bluegrass, andgospel music, writing and singing songs about family, religion, people, places, and politics. Another singer/songwriter is Lucinda Williams, who was born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, in 1953 but spent much of her childhood in Arkansas. She won a Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Album in 1998 for what is often regarded as her masterpiece, Car Wheels on a Gravel Road.

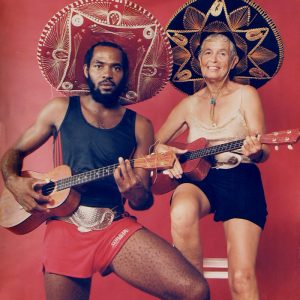

In the mid-to-late 1980s, highly visible Little Rock street musicians and eccentrics Elton and Betty White put their unique stamp on the continuing folk traditions of Arkansas with their sexually explicit and original ukulele songs. In addition, the folk-pop/rock performance duo Trout Fishing in America, based in northwest Arkansas, has been nominated for four Grammys and has released more than twenty albums.

Folk Music Organizations, Festivals, and Sites

The Rackensack Folklore Society was organized in 1963 for the purpose of perpetuating the traditional folk music of the people of Arkansas, particularly in the mountainous area of the north-central part of the state. Stone County was unique in having music-making families throughout its boundaries who founded the base of the Rackensack organization. The society was begun by Lloyd and Martha Hollister, who came from the Little Rock area in 1962 and settled in Stone County. A Pulaski County chapter of the Rackensack Folklore Society was formed in 1963 as a sister to the original chapter.

To capitalize on the rich “mountain music” and craft traditions of the area, Mountain View (Stone County) hosted the first annual Arkansas Folk Festival in 1963 under the sponsorship of the Ozark Foothills Handicraft Guild (later known as the Arkansas Craft Guild) and the Rackensack Folklore Society. In the first year, the event brought more than 2,500 visitors to Mountain View, which had a population of less than 1,000 at that time. The festival was a revival of the original 1941 folk music festival, the Stone County Folkways Festival.

Born out of the success of the Arkansas Folk Festival, the Ozark Folk Center State Park in Mountain View is dedicated to the preservation and perpetuation of southern mountain folkways and traditions. When it opened in 1973, the park was hailed as a permanent home for traditional crafts and music and has since become one of the important institutions preserving this particular way of life. Jimmy Driftwood, who was involved in the establishment of Rackensack, performed at the center’s spring 1973 grand opening, although he ceased his involvement with Rackensack soon after amid disagreements about policies. He went on to establish the Jimmy Driftwood Barn north of Mountain View, which hosts weekly musical programs portraying the folk music of the area.

For additional information:

Arkansas State Parks–Ozark Folk Center. http://www.ozarkfolkcenter.com (accessed June 27, 2025).

Cochran, Robert. Our Own Sweet Sounds: A Celebration of Popular Music in Arkansas. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

McNeil, W. K. “Singing and Playing Music in Arkansas.” In An Arkansas Folklore Sourcebook, edited by W. K. McNeil. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Ozark Folksong Collection. University of Arkansas Libraries Special Collections. http://digitalcollections.uark.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/OzarkFolkSong (accessed June 27, 2025).

Wade, Stephen. The Beautiful Music All Around Us: Field Recordings and the American Experience. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2012.

Weissman, Dick. Which Side Are You On? An Inside History of the Folk Music Revival in America. New York: Continuum, 2005.

Staff of the Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Adapted in part from the Folklore and Folklife entry by William M. Clements

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.