calsfoundation@cals.org

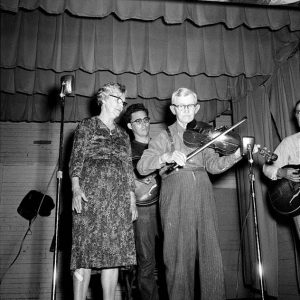

Almeda James Riddle (1898–1986)

Discovered by a ballad collector in the 1950s, Almeda James Riddle of Greers Ferry (Cleburne County) became a prominent figure in America’s folk music revival. Her memory of ballads, hymns, and children’s songs was one of the largest single repertories documented by folksong scholars. After two decades of concerts and recordings, she received the National Heritage Award from the National Endowment for the Arts for her contributions to the preservation of Ozark folksong traditions.

Almeda James was born on November 21, 1898, in the community of West Pangburn (Cleburne County). She was the fifth of eight children of J. L. James, a timber worker, and Martha Frances Wilkerson. In 1916, she married H. Pryce Riddle and started family life near Heber Springs (Cleburne County). Three of their four children survived to adulthood: Clinton, Milbry, and John Lloyd. A tornado on November 25, 1926, took the life of both her husband and their young baby.

Riddle was a widow caring for her mother and living near her grown children in Greers Ferry when John Quincy Wolf, the first “ballad hunter” in the area, found her in 1952. Wolf, a Batesville (Independence County) native teaching English at what is now Rhodes College in Memphis, Tennessee, realized that many of Riddle’s songs dated back to seventeenth-century Scotland, England, and Ireland. In his chance meeting with Riddle, Wolf had found a prolific tradition bearer. Thirty years later, the National Endowment for the Arts would pay tribute to Riddle as “the great lady of Ozark balladry,” noting that “she once listed a hundred songs she could call to mind right then, and later added she could name another hundred if she had the time.”

Recordings in 1959 by another folklorist, Alan Lomax, brought Riddle the first of many invitations to sing on college campuses around the country. At the age of sixty-two, after her mother’s death, Almeda found herself starting on her new career “of getting out the old songs,” as she put it, in person, in print, and on tape.

By the early 1960s, America’s folk music revival was picking up momentum. Riddle and other traditional singers and musicians were appearing at festivals literally coast to coast. She traveled by bus to Washington DC, Philadelphia, New York, and the Newport Jazz and Folk Festival, on to Yale University and Harvard University, to Montreal and Quebec in Canada, to Chicago and Minneapolis, and to the West Coast at UCLA and Berkeley. She frequently shared the stage with Doc Watson and Pete and Mike Seeger, as well as Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, and other dynamic new performers.

Young audiences heralded both the traditional songs and plain singing style of Riddle, an authentic contrast to formula lyrics, packaged sounds, and exaggerated performances from the contemporary music industry and entertainers. Asked when she herself first noticed the sea change in American music since her childhood, Riddle pointed to the popularity—and popularizing—of Elvis Presley. “Elvis was a good boy, and I liked him alright,” she admitted, “but he and others got to performing. They got out in front of the music. And performance took over music.”

With the help of folklore scholar Roger Abrahams, Riddle recorded more than 200 of her childhood favorites, fifty of which were transcribed in the book A Singer and Her Songs: Almeda Riddle’s Book of Ballads. Abraham’s book challenged the stereotype of traditional singers as uneducated hill people. To the contrary, their “high, lonesome” style was learned, and many could read music. Riddle’s own father taught at singing schools held in summers between planting and harvest. “He made us learn the round note, but the shape notes are quicker read,” Riddle said of her father. “We learned both the four and the eight note system. And anything I know the tune to,” she told Abrahams matter-of-factly, “I can put the notes to.”

Her extensive repertory included American variants of the ballads collected by Harvard folklorist Francis Child in his traverse of the Scottish and English countryside in the 1880s. Riddle also sang the songs about railroaders and cowboys that had spread through her part of the Ozarks—as well as the rest of turn-of-century rural America—often via newspapers first, before entering into oral tradition. Her versions of children’s songs like “Go Tell Aunt Rhody” and “La La Chicka-la-leo,” the latter a rare English nursery song, were frequent requests at concerts.

While the source and lyrics of these American variants held primary interest for early folksong scholars, later generations of folklorists like Abrahams became equally focused on questions of the meaning and function of a song in the life of the singer. Among the hundreds Riddle could sing on request, she told Abrahams it was the older narrative ballads and the shape-note hymns that she preferred and sang most often. “I never really cared too much for a song that didn’t tell a story or teach a lesson,” she remarked.

As folk music became newsworthy and folk festivals became big business, reporters and promoters gave Riddle bigger and longer titles. Headlines shifted from simply “Mrs. Almeda Riddle” to “Granny Riddle” to “balladeer” to “folk artist of the Arkansas Ozarks.” Though the publicizing made her uncomfortable, Riddle turned the concerts and coverage into a grandmother’s duty and kept on traveling. “Well, the kids kept begging for the old songs,” she told a younger musician. “If you had a child standing there hungry with a hand out for bread, and you had the bread, you’d hand out the bread as long as you had bread. And God gave me the strength to go, and I went,” she added.

Riddle’s final in-state performance came in 1984 at the Ozark Folk Center in Mountain View (Stone County). Joined there by Mike Seeger, she sang “From Jerusalem to Jericho,” a camp meeting song about the parable of the Good Samaritan—which she promptly turned into another lesson for herself. “I’ve often thought about that myself, and I’m as guilty as the next,” she admitted to the audience. “But in my 85 years, I’ve seen a lot of it—people who are like the letter ‘p’: they’re first in pity and the last in help.”

This appearance closed out Riddle’s twenty-two years of getting out the old songs. In December 1984, she moved into a nursing home in Heber Springs where she died on June 30, 1986. She is buried next to her husband at Shiloh Cross Roads Cemetery.

A final album of Riddle’s favorite and previously unrecorded hymns and semi-sacred songs, How Firm a Foundation, was released in 1985. The revised edition of A Singer and Her Songs was started the same year. A half-hour television documentary, “Now Let’s Talk About Singing”: Almeda Riddle, Ozark Singer, was produced in 1986 and aired on the Arkansas Educational Television Network (AETN).

For additional information:

Abrahams, Roger, and George Foss, eds. A Singer and Her Songs: Almeda Riddle’s Book of Ballads. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1970.

How Firm a Foundation: Favorite Hymns and Other Sacred Songs of Almeda Riddle. Mountain View: Arkansas Traditions, 1985.

John Quincy Wolf Folklore Collection. Regional Studies Center. Lyon College, Batesville, Arkansas. Online at https://www.lyon.edu/john-quincy-wolf-collection (accessed July 11, 2023).

Nelson, Sarah Jane. Ballad Hunting with Max Hunter: Stories of an Ozark Folksong Collector. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2023.

Randolph, Vance. Ozark Folk Songs. 4 vols. Columbia: State Historical Society of Missouri, 1947–1950.

Stark, Merrelyn. “Interview with Almeda Riddle.” Cleburne County Historical Society Journal 16 (Fall 1990): 81–102.

George West

Little Rock Central High School

Almeda Riddle

Almeda Riddle

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.