calsfoundation@cals.org

European Exploration and Settlement, 1541 through 1802

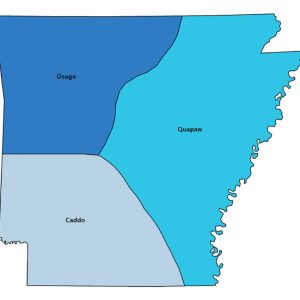

The region that became Arkansas was unknown to Europeans until the 1540s. Fifty years after Christopher Columbus landed in the western hemisphere, the European exploration of Arkansas began. The first settlement was not founded for another 140 years, and the first permanent settlement forty years after that. Throughout the colonial era, Arkansas underwent dramatic demographic changes. At the time of the first Spanish explorers in the 1540s, Arkansas was a land of heavily populated villages and extensive farm fields. By the time of the first French expeditions in the 1670s, Arkansas was sparsely populated with isolated villages and tribes but with an abundance of wild game and other resources. The focus of the colonial era was not on the promotion of substantial immigration but on the exploitation of wild game for trade. By the end of the colonial era, Arkansas had attracted individuals and families of diverse races and ethnicities. People of French, Spanish, German, Dutch, Anglo-American, and African descent joined the Indian peoples of Arkansas and a myriad of tribes from across the continent.

Explorers

On June 18, 1541, Hernando de Soto’s Spanish expeditionary force crossed the Mississippi River and became the first Europeans to enter Arkansas. For the next two years, the Spaniards explored through Arkansas with a large number of captive Indians. The expedition began on the gulf coast of Florida and for two years had explored what is now the American South. The expedition’s goal was to find a North American kingdom of gold on the scale of the Aztecs of Mexico, who had been conquered by the Spanish twenty years earlier. De Soto and his men were sorely disappointed. They found not cities of gold but numerous, well-populated villages supported by vast fields of maize. The Spaniards had entered the Mississippian Period world noted for their mound-building and hierarchical political systems. Powerful chiefs controlled several villages that provided tribute to them. In Arkansas, de Soto found some of the largest villages, like Pacaha and Casqui in the northeast, and the most powerful chiefs in the South. They killed numerous natives, gorged themselves on native food stores, and disrupted the region’s political systems—weakening some and supporting others, though the former was much more common.

Scholars have long debated the route of de Soto’s expedition through Arkansas and the South. The most recent mapping of the route through Arkansas follows the expedition across northern Arkansas to the Arkansas River. De Soto’s men crossed the river downstream from present-day Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and headed southeast. They continued until they were nearly to the mouth of the Arkansas River. They then followed the Mississippi River south for a short distance before returning to the Arkansas River. On May 21, 1542, de Soto died in the town of Guachoya in southeastern Arkansas (present-day Lake Village in Chicot County). Luis de Moscoso succeeded him as captain general and governor of the expedition. By this time, the Spaniards were ready to end the expedition, and Moscoso led them across southern Arkansas to the Red River in hopes of finding their way to the colony of New Spain (what is now Mexico). At this time, the expedition suffered its only desertion—Francisco de Guzman had fallen in love with an Indian woman and remained in the territory of Chaguate on the Ouachita River. Continuing without Guzman, the expedition crossed the Red River, but their southwest direction seemed to lead them no closer to New Spain. They turned around and traveled back across southern Arkansas. Returning to the Mississippi River, they built new boats and, in the spring of 1543, floated downriver to the Gulf of Mexico and then to New Spain.

Moscoso and his men were the last Europeans to see Arkansas for 130 years. In the summer of 1673, another European expedition arrived in Arkansas. Canoeing down the Mississippi River from the Illinois country (the upper Mississippi River Valley), Father Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit missionary, and Louis Joliet, a coureur de bois (a trader who lived in Indian country), led a French expedition that was much smaller than de Soto’s. The expedition’s mission was to explore the Mississippi River Valley and find the mouth of the river. Their hope was that the river flowed west and might be a route to the Pacific. It was the first step to extend French influence into the middle of the continent in order to convert the native peoples and set up a French-Indian trade network. Near the mouth of the Arkansas River, the Frenchmen encountered the Quapaw, whom they called the Arkansas, and named the river and the region after the tribe. The expedition stayed several days among the Quapaw and learned that the mouth of the Mississippi River was not far to the south. The Quapaw also warned them that downriver there were strong tribes of Indians who might kill the French. Fearing for their safety, Marquette and Joliet decided not to continue and returned to Illinois.

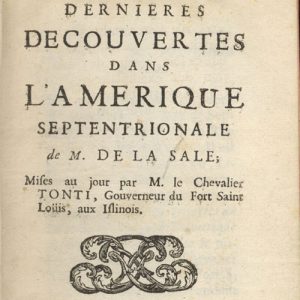

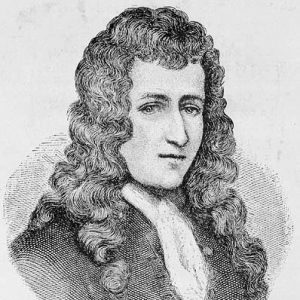

Marquette reported what his expedition had found to officials in the colony of New France (Canada). His report led to a larger French expedition nine years later. With royal approval, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, commanded and equipped this expedition. On this expedition were twenty-three Frenchmen and thirty-one Indians. The seventeen or eighteen Indian men were identified as Mohegan, Abenaki, Sokoki, and Lous. The ten women, who had three children with them, were Abenaki, Huron, Nipissing, and Ojibwa. All of them were from tribes—extending from New England across Canada to the Great Lakes—who were allied with the French. The La Salle expedition then was less an expansion of the French empire and more of an extension of a vast French-Indian trade and military alliance.

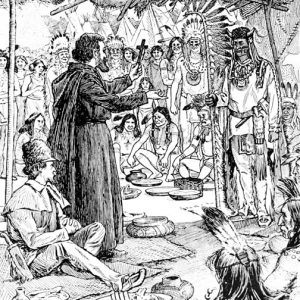

Searching for the mouth of the Mississippi, La Salle’s expedition stopped at the Arkansas River. There they were treated to a feast and ceremony in which La Salle and Quapaw leaders smoked the calumet pipe. In the French mind, an alliance had been created, but for the Quapaw, the calumet ceremony signified the creation of fictive kinship between the two peoples with similar connections as blood relations. La Salle led his expedition to the mouth of the river where, according to European legal conventions, he claimed the whole Mississippi River Valley for France. On his return upstream, La Salle again stayed with the Quapaw but left quickly in order to report his success to French officials.

La Salle planned to colonize the region near the mouth of the Mississippi. In 1684, with a charter from the King of France, La Salle set sail from France with colonists, but they could not find the mouth of the Mississippi and landed instead on the Texas gulf coast. Soon after, La Salle was assassinated and many colonists were killed by neighboring Indians or captured by the Spanish. Three survivors—Henri Joutel, Anastase Douay, and Jean Cavelier, La Salle’s younger brother—traveled across eastern Texas into Arkansas, following nearly the same route as Moscoso did one hundred and forty years earlier.

When Joutel and his companions arrived at the Arkansas River, they discovered the newly established Arkansas Post (near Lake Dumond in present-day Arkansas County), which Henri de Tonti, La Salle’s longtime partner, founded in 1686 to serve as a way-station between Illinois and La Salle’s proposed colony in the lower Mississippi River Valley. Tonti left six men at Arkansas Post to watch for La Salle’s return from his expedition of colonization. Tonti also wanted to begin trade with the Quapaw, who he assumed would be his principal hunters. Arkansas Post was the only European settlement west of the Mississippi at the time. By the time Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville founded the Louisiana colony on the Gulf Coast in 1699, Arkansas Post had been abandoned. The Frenchmen at the post had deserted, at least one of them to aid the English.

Twenty years after the founding of Louisiana, exploration continued into the western regions of the colony. By 1719, Jean Benard de la Harpe had explored the upper Red River and into the land between the Red and Arkansas rivers (present-day eastern Oklahoma). Just west of the Great Bend of the Red River, he established a trading post and garrison, named St. Louis de Caddodoches, on the south bank among the Kadohadacho Confederacy of the Caddo, who lived in southwestern Arkansas and along the Red River. The garrison was the only outpost in the region of the upper Red and Ouachita rivers until the 1780s. Two years later, La Harpe led the first French expedition up the Arkansas River to near present-day Morrilton (Conway County).

Missionaries

By the end of the seventeenth century, French missionaries followed in the path of the explorers to Arkansas. Like Marquette, few stayed in Arkansas, but often they were witnesses to disease epidemics that ravaged the Quapaw and other native peoples of the region. In 1699, several missionaries from the Recollect order, a French branch of the Franciscans, descended the Mississippi River in the aftermath of one of the worst smallpox epidemics to hit the Mississippi River Valley and the southeast. A little more than twenty years later, Father Pierre Charlevoix recorded the effects of another smallpox epidemic. None of these missionaries stayed for more than a few days in the Quapaw villages. Their destination was the lower Mississippi River, but they promised the Quapaw that missionaries would be sent to them.

In 1700, the promised missionary arrived in the person of Father Nicolas Foucault. He found, however, that the Quapaw resisted his attempts to convert them. He did not remain long and soon after his departure, he was killed by a party of Koroa, who lived downstream and were enemies of the Quapaw. In retaliation, the Quapaw attacked the Koroa and nearly wiped them out.

It would be another twenty-five years before another missionary attempted to establish a mission among the Quapaw. In 1727, Father Paul du Poisson made the second attempt to convert the Quapaw. The Quapaw perceived him as a man of great power and referred to him as Panianga sa, the Black Chief, most likely because of the black attire worn by Jesuits. The esteem in which du Poisson was held had important implications for French-Quapaw relations. His prestige, and not just trade and material concerns, became a factor in the developing alliance between the Quapaw and the French. Du Poisson’s death at the beginning of the Natchez War in 1729 helped prompt the military alliance between the Quapaw and colonial Louisiana. Serving as the substitute for the regular priest at the chapel in Natchez, du Poisson had been there when the Natchez launched their initial attack, and he was one of their first victims. In 1729, the Quapaw joined the French counterattack against the Natchez and their allies. Du Poisson’s death provided the Quapaw with their own reasons for going to war against the Natchez. With the help of the Quapaw and other Indian allies, the French defeated the Natchez and forced them to find refuge among other tribes.

After du Poisson, French priests were rare at Arkansas Post. Not until the 1790s was there a regular priestly presence. In 1792, Father Pierre Gibault arrived to form a mission for the New Madrid Parish. He stayed only a year and his successor stayed for less than that. Then, in 1796, St. Stephen Parish was founded, the first canonical parish at Arkansas Post, with Father Pierre Janin as priest. It lasted for only three years; when Janin was transferred to St. Louis, the parish closed.

Trade and Settlement

By the time Father du Poisson arrived in Arkansas, Arkansas Post had been re-established near the location of Tonti’s post. The post remained at this spot until 1749, when it was moved upriver to Ecores Rouges (Red Bluffs), where the Arkansas Post National Monument is now located. In 1756, during the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the post moved downriver again but on the south bank and closer to the mouth of the Arkansas River, so that the garrison could support French military and commercial activities on the Mississippi River. Despite the end of the war, the post remained there until 1779. That year, after numerous colonists’ protests about the constant flooding, the post was moved back to Ecores Rouges.

It was reestablished in 1721 after Scotsman John Law and his Compagnie d’Occident (The Company of the West), a joint-stock company, acquired control of the colony of Louisiana through a charter granted by the King of France. The charter required the company to recruit colonists and to grant land to individuals for the establishment of concessions or plantations. John Law received one of the largest concessions located on the Arkansas River. Law’s concession led to the reestablishment of Arkansas Post. In August 1721, engages (or indentured servants who were contracted to serve for a set period) established the concession and were joined a month later by a small detachment of French soldiers. In the early 1720s, forty-seven inhabitants resided there. They included a storekeeper, a surgeon, an apothecary, and a military garrison led by a commandant, but most were indentured servants. By the next year, Law was bankrupt, and no more colonists arrived. Some of the engages were released from their indentures and remained. They became hunters and traders, but only a few of them tried their hands at agriculture. In 1723, however, only twenty persons remained on the concession, including the first African Americans in Arkansas, all six of whom were slaves. Two years later, the garrison was abandoned but was re-established in 1731 by the royal government. That year, the Company of the West went bankrupt, and the royal government of France regained control of the colony. The Arkansas Post remained in continuous, though tenuous, existence throughout the colonial period.

The remaining settlers began hunting and trading hides and other animal products. Throughout the eighteenth century, the vast majority of the population of Arkansas was engaged in hunting or the fur and skin trade as bourgeois (trading post managers), engages (hired hands), and hunters. By 1712, the French had learned of the abundance of bears in Arkansas and the value of bear oil, which was used for cooking, as a protection against mosquitoes, or (when applied to the body) as a cure for rheumatism. The French and the Quapaw hunted and traded for bear oil, tallow, buffalo meat, and skins and shipped them to New Orleans.

In this economy, these traders were joining the Quapaw who were already hunting and processing animal products not only for subsistence but for trade with the French. The complementary economy of the two peoples in Arkansas was the beginning of a middle ground, a mixing of culture between French and Indians. In contributing to this middle ground, the French in Arkansas followed a familiar pattern. In the early eighteenth century, many of the French men in the Mississippi River Valley had come from Canada, and they helped determine the cultural and gender relations in the region. They were the coureurs de bois, Frenchmen who traded and lived among the Indian peoples in New France. Within the frontier environment of New France, the coureurs de bois were able to assert independence from colonial authority and create relationships with the Indians of New France. By the late seventeenth century, those relations extended as far as the Great Lakes and the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. The Canadian coureurs de bois who made their way down the Mississippi found it much easier to make a living by hunting and fur trading than by farming in the cold climate and short growing season of Canada. The accessible river, the system of Indian allies, and the French government’s need for individual Frenchmen to secure allies for trade and defense in the Mississippi River Valley all drew the Canadians southward.

The Canadians were not alone in forming this new colonial society in the Mississippi Valley. In 1699, the first settlers of the Louisiana colony found a situation similar to that in New France. They were forced to rely on neighboring Indians for food and, due to the lack of female immigrants, they quickly became intimate with native women.

French hunters were first drawn to the St. Francis River. The river’s mouth at the Mississippi River made it easily accessible to the hunters. Moreover, the bottomland forests and canebrakes at the mouth of and along the St. Francis River provided excellent habitat for a number of wild game, especially bison and bears. These hunters were the principal suppliers of buffalo tallow, bear oil, and buffalo meat to New Orleans and the lower Mississippi Valley. Acquiring the meat of wild game was necessary in early colonial days because of the lack of cattle and enough cleared land to raise them. At the end of every summer, hunters from Canada and the lower Mississippi River traveled on the great river to rendezvous at the St. Francis River, where they remained through the winter. Once the hunting season was over, the hunters collected their products and began the process of making bear’s oil, a skill they learned from the Indians, and preserving the meat. One technique of meat preservation was to cut the meat from bison flanks into strips and dry it in the sun. The other was to salt the meat. The area around the St. Francis River proved valuable in the latter process because salt was easily available in the area. Throughout Arkansas, salt springs had long supported an Indian trade in salt. Besides being used to preserve the meat, salt was also sold in New Orleans. The success of the hunters was evident yearly. On one occasion in 1726, two Canadians supplied 480 tongues of bison to New Orleans.

Throughout the eighteenth century, there were few farmers or planters. In the last two decades of the century, a few farming families—French from the Illinois country, Anglo-Americans, and German Protestants—arrived.

Military officers stationed at Arkansas Post were the center of the upper class. They were well-educated gentlemen with only the few prosperous merchants on the Arkansas River as their social equals. The commandants of Arkansas Post had to vigilantly protect the post and traffic on the Mississippi River connecting Illinois to New Orleans from Chickasaw raiders, who were allies of the British. Often, the alliance with the Quapaw countered the anti-French Chickasaw. The post stood until May 10, 1749, when the Chickasaws attacked and destroyed the post. Six men and eight women and children were captured. The men were later executed in retaliation for the near fatal wounding of Chickasaw chief Payah Matahah during the raid. The women and children were later ransomed from the Chickasaw or released to British officials in Charleston, South Carolina, where the Chickasaw often traded. The commandant of Arkansas Post, First Ensign Louis-Xavier-Martin Delino de Chalmette, was forced to move the post upstream to Ecores Rouges for better protection and to be closer to the Quapaw, who had moved there the year before.

Seven years later, the French colonial government ordered the post moved closer to the Mississippi River to defend French traffic from Chickasaw and British raids. Defense had become a priority for Louisiana as a result of the French and Indian War. Other than the relocation of the post, the war had little direct effect on Arkansas. However, the post-war consequences did.

By 1760, Great Britain had defeated France in North America and gained control of Canada. The war officially ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1763, but Louisiana, including Arkansas, had already passed from French hands on November 3, 1762, to their ally, Spain.

Still, the inhabitants of the Arkansas Post were French. Few Spaniards made their way to Arkansas except for a few commandants. Spain did not gain effective control of the colony or Arkansas until the end of the decade. The delay was a combination of the distance for communication and transportation, the weakness of the Spanish empire and its relative lack of concern about Louisiana, and a short-lived rebellion in New Orleans against Spanish rule. Even then, French-born officers were likely to be appointed to command the garrison on the Arkansas River. In the 1770s and 1780s, commandants under Spanish governance navigated an uncertain situation. They had to demonstrate Spanish friendship and hospitality to the Quapaw and other pro-French Indians in the region and regulate (often encouraging) the immigration of diverse native peoples to counter the growing threats from the Osage in the west and the British presence on the Mississippi.

Spanish commandants at the Arkansas Post proved crucial in negotiating peace with the pro-British Chickasaw. The most dangerous threat to sustained peace came during the American Revolutionary War, when the Spanish aided the fledgling United States. In 1783, a combined British-Chickasaw force attacked the post, killing three soldiers and carrying off several captives who were quickly rescued by a combined Spanish-Quapaw force. The end of the Revolutionary War brought about a dramatic change in the political geography of the region. The British ceded their claim to the east bank of the Mississippi River to the United States, and the Chickasaw found themselves without their most valuable ally. Peace between the Chickasaw and the Quapaw and the Spanish was achieved by the middle of the decade.

The post’s commandant, Captain Balthazar de Villiers, achieved another critical change. In 1779, Villiers, who served for nearly six years as commandant, persuaded Bernardo de Galvez, the governor of Louisiana, to permit the return of the post to Ecores Rouges. Higher ground there reduced the threat of flooding and proved more beneficial to settlement. Flooding, especially at the downstream location close to the mouth of the Arkansas, frequently hindered farming and any other activity. Arkansas Post, like most of the settlements of the lower Mississippi Valley, often relied on food supplies from Illinois or neighboring Indians. The colonists also visited Quapaw villages to acquire food and, by the late eighteenth century, horses.

Another problem for farming was that only a certain amount of good riverfront property was available. Over the course of the eighteenth century, the French attempted to alleviate the problem by moving away from the system of plantations and adopting the property system common in New France along the St. Lawrence River. In order for more landowners to acquire property on the river, Louisiana plantations and habitations were formed into longlots, strips of land up to ten times as long as they were wide fronting the Mississippi River and, eventually, its tributaries. Along the Arkansas River, the longlot system prevailed during the Spanish regime (1763–1800) and maybe earlier.

Even with the move upriver and the longlot system, agriculture still did not become the focus of economic activity at Arkansas Post. Most of those who were most involved in agriculture were also merchants. By the last two decades of the eighteenth century, major farming activity centered around three French farming families who arrived from Illinois in 1787, one of which built the first flour mill at the post, and five German Protestant families who arrived soon after. Historian Morris Arnold believes that “there were never more than eight or ten real farmers at any one time at the Post in the colonial period.”

A small gentry class, headed by the commandants, led the post. The commandants were the civil and military judges of the post but usually remained in residence only three to four years. This class of gentry was descended from the troupes de la marine, French colonial soldiers, and their families who formed a colonial aristocracy loyal to the French king and the governor of the colony. The Spanish regime also cultivated its form of a loyal military class. The military gentry were well educated and refined and in order to attract them to outposts, the government granted them the privilege of trading with settlers and neighboring Indians. Often officers asked for and received a trading monopoly with an Indian tribe. Trade could prove lucrative for Arkansas Post officers, many of whom encouraged tribes’ hunting and immigration.

Arkansas Post’s population included non-military gentry as well. Most of all, they were the most prosperous merchants who were considered the social equals of the military officers and were often given the respect due to the gentry. At any time, however, there were only four or five of these men. No matter their class and social status, all of the inhabitants of Arkansas Post enjoyed each other’s company for drinking, gambling, and dancing. By the end of the colonial era in 1802, Arkansas Post itself, with a population of nearly 400, was an ethnically and racially diverse community. At least five languages—French, Spanish, German, English and Quapaw—as well as other Indian languages, were spoken at the post.

A small number of slaves and even fewer free “mulattoes” and free blacks resided at Arkansas Post. Most slaves were African or of African descent, but a few, especially in the early years of the post, were Indian. The Spanish, however, outlawed the enslavement of Indians. In 1798, there were fifty-six slaves at Arkansas Post, some of whom worked in the farm fields. By the late eighteenth century, most Arkansas Post farmers owned a few slaves for field work. Slaves, as well as free blacks and mulattoes, also worked as domestics, artisans, and workers in the fur and skin trade—dressing and packing hides and loading carts and boats.

Although there was much diversity in interracial marriages, most unions were between Quapaw women and French men. Besides Quapaw, church records reveal Osage and Kansas from the prairies and plains to the west; Abenaki, who had moved from northern New England; Cherokee from the southeast, and Delaware from the northeast. The records mentioned several from the Padouca or Padot nation, the name the French gave to some Plains Indians. Early in the eighteenth century, the name Padouca referred to Plains Apaches, but by the 1790s, the time of most of the records, the term usually referred to Comanche. One woman, Marie Anne, was identified as a Laitanne, another band of the Comanche. Many of these women were captives who had then been given to French men engaged in the Indian trade. Among the captives who became Arkansas wives were two women from New Mexico.

The men at Arkansas Post who married Indian and metis (of mixed Indian and European descent) women were of French, English, and Spanish descent. Two of the Anglo-Americans were from Pennsylvania and Maryland. There were occasions when two metis were married, but there is only one record of the marriage of two Indians: Marie, an Abenaki, and Jean Baptiste Sans Cartier, a Comanche. Links between members of the metis community were strengthened as they participated as witnesses and godparents in the sacramental rituals of the church.

New Posts and the Louisiana Purchase

In the 1780s, the Spanish colonial government also realized the need for an additional post on the Ouachita River between the posts at Arkansas and Natchitoches. The settlement at St. Louis de Caddodoches had been abandoned in 1778 except for a small garrison of soldiers, and there was no colonial governmental presence on the upper Red or Ouachita rivers. In 1782, Jean de Filhiol initially attempted to build a post at Ecore a Fabri, present-day Camden (Ouachita County). By 1784, he had moved downriver to establish the Poste du Ouachita, later known as Fort Miro, on the present site of Monroe, Louisiana.

Ecore a Fabri was just one place where Ouachita hunters established caches to store and hide their bounty and rendezvous to trade along the river. Their names dotted maps of the region in the late eighteenth century: Cache a Macon, Cache a la Tulipe, Champagnolle, and Bayou de Moreau (or Moro). The hunters were of many nationalities besides French, and they competed with numerous Indian hunters. They went up the Ouachita River and its tributaries to the Ouachita Mountains and the hot springs and to the numerous game-attracting salt licks of the Saline River. These men hunted in a region that had changed little since the survivors of the La Salle expedition wandered and hunted across southern Arkansas. The tradition of hunting continues in those forests and river bottoms.

In 1795, the Spanish also established San Fernando de las Barrancas on the Chickasaw Bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River. Two years later, the signing of the Treaty of San Lorenzo, which Americans called Pinckney’s Treaty, set the Mississippi River as the definite boundary between Spanish Louisiana and the United States. The United States gained control of the east bank of the river, and the Spanish moved their east bank garrisons across the river. As part of the trans-river transfer, San Fernando de las Barrancas was moved to present-day Crittenden County and renamed Campo de la Esperanza (Hopefield). Benjamin Fooy, a Dutchman who served Spanish Louisiana as an Indian agent and interpreter, supervised the establishment of the new garrison. The area was on the path southeastern Indians used for trade and hunting in Arkansas and the Mississippi Valley and therefore critical to Spanish diplomacy to maintain friendship with the region’s Indians. Interestingly, these two posts were established near the area where de Soto’s expedition had crossed the river 250 years earlier.

In May 1803, France and the United States signed the treaty for the Louisiana Purchase. Arkansas once again peacefully changed governments and was now a part of the young republic. On March 10, 1804, Captain George Carmichael accepted the transfer of Campo de la Esperanza to the United States. Thirteen days later, Lieutenant James Many officially took possession of Arkansas Post for the United States.

For additional information:

Arnold, Morris S. Colonial Arkansas, 1686–1804: A Social and Cultural History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

———. The Rumble of a Distant Drum: The Quapaws and Old World Newcomers, 1673–1804. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

———. “The Soldiers of France in Colonial Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Winter 2021): 403–435.

———. Unequal Laws unto a Savage Race: European Legal Traditions in Arkansas, 1686–1836. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1985.

Bolton, Herbert, ed. Athanase de Mezieres and the Louisiana-Texas Frontier, 1768–1780. Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1914.

DuVal, Kathleen. “The Education of Fernando de Leyba: Quapaws and Spaniards on the Borders of Empires.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60 (Spring 2001): 1–29.

———. The Native Ground: Indians and Colonists in the Heart of the Continent. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Faye, Stanley. “The Arkansas Post of Louisiana: French Domination.” Louisiana Historical Quarterly 26 (July 1943): 633–721.

———. “The Arkansas Post of Louisiana: Spanish Domination.” Louisiana Historical Quarterly 27 (July 1944): 629–716.

Hudson, Charles. Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South’s Ancient Chiefdoms. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997.

Key, Joseph Patrick. “The Calumet and the Cross: Religious Encounters in the Lower Mississippi Valley.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 61 (Summer 2002): 152–168.

Scott, Robert J. “Investigating the Causes and Consequences of Depopulation in Southeast Arkansas, A.D. 1500–1700.” PhD diss., Southern Illinois University Carbondale, 2018.

Toudji, Sonia. “Intimate Frontiers: Indians, French, and Africans in Colonial Mississippi Valley.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2012. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/344/ (accessed August 3, 2023).

Usner, Daniel H., Jr. Indians, Settlers and Slaves in a Frontier Exchange Economy: The Lower Mississippi Valley before 1783. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

West, Cane W. “Learning the Land: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in the Southern Borderlands, 1500–1850.” PhD diss., University of South Carolina, 2019.

Whayne, Jeannie, ed. Cultural Encounters in the Early South: Indians and Europeans in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Joseph Patrick Key

Arkansas State University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.