calsfoundation@cals.org

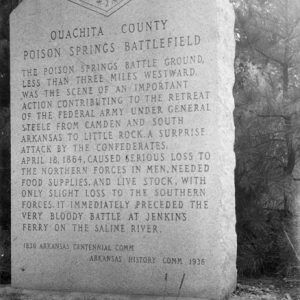

Engagement at Poison Spring

| Location: | Ouachita County |

| Campaign: | Camden Expedition (1864) |

| Date(s): | April 18, 1864 |

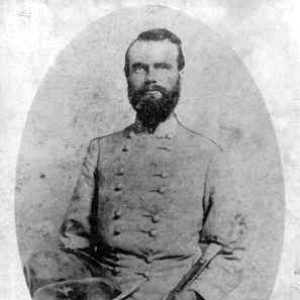

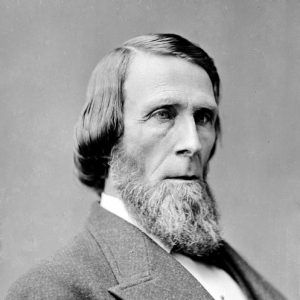

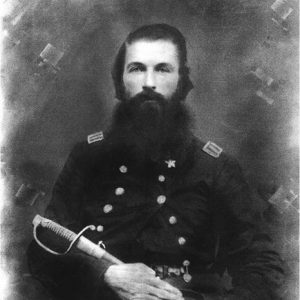

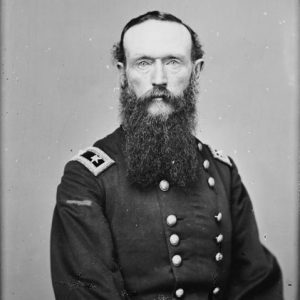

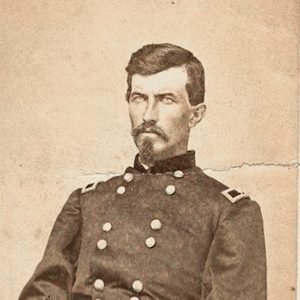

| Principal Commanders: | Colonel James M. Williams (US); Brigadier General John Sappington Marmaduke and Brigadier General Samuel Bell Maxey (CS) |

| Forces Engaged: | Brigade (1,169 men) [US]; Marmaduke’s and Maxey’s Divisions (approximately 3,600 men) [CS] |

| Estimated Casualties: | 301 (US);114 (CS) |

| Result(s): | Confederate victory |

The Engagement at Poison Spring was an April 18, 1864, battle in which Confederate troops ambushed and destroyed a Union foraging expedition. After black Union troops had surrendered, many were killed by the Confederate troops.

After capturing Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Fort Smith (Sebastian County) in September 1863, Federal forces held effective control of the Arkansas River, and both Confederate troops and government were concentrated in the southwestern part of the state. In the spring of 1864, many of the Union troops were involved in the Arkansas leg of a two-pronged attack to gain control of northwestern Louisiana and eastern Texas.

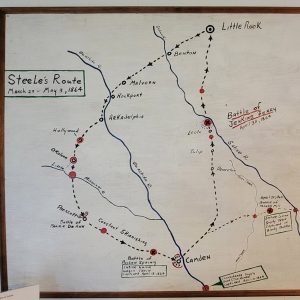

Union Major General Frederick Steele moved his troops south from Little Rock on March 23, 1864, for what became known as the Camden Expedition. After battles at Elkin’s Ferry and Prairie D’Ane, Steele turned his army toward Camden (Ouachita County) on the Ouachita River, arriving there on April 15. Relatively safe within Camden’s fortifications, Steele then addressed his critical lack of supplies.

On April 17, Steele sent a force of over 600 men and four cannon under Colonel James M. Williams with 198 wagons to seize 5,000 bushels of corn that were reportedly stored west of Camden. Marching to White Oak Creek some eighteen miles from Camden, Williams sent his troops, which included the First Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment, into the surrounding countryside to gather corn at area farms and plantations. Though Confederate cavalry had managed to destroy about half of the corn, the Yankee troops gathered the remainder, as well as other plunder, and regrouped at White Oak Creek. Williams was joined the next morning by a 501-man relief force of infantry, cavalry and two additional artillery pieces.

Confederate Brigadier General John Sappington Marmaduke, meanwhile, positioned approximately 3,600 rebel cavalrymen backed by twelve cannon between Williams’s column and Camden, blocking the Camden-Washington Road near Poison Spring. In addition to Arkansas, Missouri and Texas horsemen, his force included Colonel Tandy Walker’s Choctaw Brigade from the Indian Territory.

Williams encountered the Confederate troops blocking the road on the morning of April 18 and established an L-shaped defense around his wagon train. The First Kansas Colored Infantry, recruited from former slaves from Arkansas and Missouri, fought off two attacks. A third, well-coordinated attack by four Confederate brigades broke the First Kansas line, and the entire Federal force retreated. Rebel troops followed them for two and one-half miles before calling off the pursuit. The Southern troops then turned their attention to the wounded and captured soldiers of the First Kansas; both Union and Confederate accounts agree that many of the black troops were killed after the battle was over. Williams lost 301 men killed, wounded and missing at Poison Spring. Of those, 117 of the dead and sixty-five of the wounded were from the First Kansas Colored Infantry. Confederate losses were incompletely recorded but are believed to be fewer than 145.

A small portion of the Poison Spring battlefield is now preserved as Poison Spring Battleground State Park near Bragg City (Ouachita County).

For additional information:

Christ, Mark K. “‘War to the knife’: Union and Confederate Soldiers’ Accounts of the Camden Expedition, 1864.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 73 (Winter 2014): 381–413.

Christ, Mark K., ed. “All Cut to Pieces and Gone to Hell”: The Civil War, Race Relations, and the Battle of Poison Spring. Little Rock: August House, 2003.

Ringquist, John Paul. “Color No Longer a Sign of Bondage: Race, Identity and the First Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry Regiment (1862–1865).” PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2011. Online at https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/handle/1808/8372 (accessed July 6, 2023).

Urwin, Gregory J. W. “‘We Cannot Treat Negroes… as Prisoners of War’”: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in Civil War Arkansas.” In Civil War Arkansas: Beyond Battles and Leaders, edited by Anne Bailey and Daniel Sutherland. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Mark K. Christ

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.