calsfoundation@cals.org

First and Second Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry Regiments

aka: Seventy-Ninth and Eighty-Third United States Colored Troops

The First and Second Kansas Colored Infantry Regiments were African American Union Civil War units that were involved—one as victim and one as perpetrator—in racial atrocities committed during the 1864 Camden Expedition.

James H. Lane began recruiting the First Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment in August 1862—months before the Emancipation Proclamation took effect and active efforts to recruit Black soldiers began—and the regiment saw action at Island Mound, Missouri, on October 29, 1862, in a victory that produced the first Black combat casualties of the Civil War. The First Kansas also initially had two Black officers, Captain William Matthews and Second Lieutenant Patrick H. Minor, but neither were mustered in when the regiments entered Federal service, as only white officers were accepted.

The First Kansas was formally organized at Fort Scott, Kansas, on January 13, 1863. The regiment served in Kansas, Missouri, and the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), where it participated in the Union victories at Cabin Creek and Honey Springs in the summer of 1863. The regiment joined the garrison at Fort Smith (Sebastian County) in October 1863.

The Second Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment was organized at Fort Scott and Leavenworth, Kansas, between August 11 and October 17, 1863. The regiment’s Company A was among the Union troops at Baxter Springs, Kansas, on October 6, 1863, that fought off William Quantrill’s guerrillas after they massacred Major General James G. Blunt’s escort. The regiment joined the garrison at Fort Smith on October 19, 1863.

Both regiments were part of Brigadier General John M. Thayer’s Frontier Division during the Camden Expedition, joining Major General Frederick Steele’s main Federal army shortly after the Engagement at Elkin’s Ferry and in time to participate in the fighting at Prairie D’Ane and Moscow. The combined force occupied Camden (Ouachita County) on April 15, 1864.

Two days later, the First Kansas Colored was part of a foraging party sent out to capture a reported cache of Confederate corn west of Camden. As they headed back toward Camden, laden not only with corn but with booty seized from private homes, Brigadier General John Sappington Marmaduke’s Confederates attacked the wagon train at Poison Spring on April 18. After a desperate battle, the Union force collapsed, and Confederate troops, many from Colonel Tandy Walker’s Choctaw regiment, roamed the battlefield killing wounded and surrendered First Kansas soldiers. A Confederate soldier later wrote to his wife that “if the negro was wounded our men would shoot him dead as they passed and what negroes that were captured…have since been shot.” Of the 204 Federals killed or missing and ninety-seven wounded at Poison Spring, 117 dead and sixty-five wounded were from the First Kansas Colored.

Another Union wagon train was destroyed at Marks’ Mills a week later, with many of the Black teamsters and refugees accompanying it murdered after the battle, leading Steele to abandon Camden and head back to Little Rock (Pulaski County) while he still had an army to save. They quietly left the town on April 26, but Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith’s Confederates caught up with them on April 29 as the Federals approached the swollen Saline River at Jenkins’ Ferry.

The next day, the Confederates launched several disjointed attacks against the Union rear guard, suffering heavy casualties. As a Missouri artillery battery unlimbered its cannon to fire on the Federal troops, the Second Kansas Colored Infantry charged, screaming, “Remember Poison Spring!” They overran the battery, bayoneting three men as they tried to surrender; an accompanying Iowa regiment kept them from killing additional men at the battery. The vengeful Kansans killed many wounded Confederates after the battle, with a wounded Texan writing that, after the rebels fell back, “I looked around and saw some black negroes cutting our wounded boys’ throats.” An Arkansas soldier reported that “we found that many of our wounded had been mutilated in many ways. Some with ears cut off, throats cut, knife stabs, etc. My brother…was shot through the body, had his throat cut through the windpipe and lived several days.” Nine wounded Second Kansas men were later killed by Confederate soldiers.

Both regiments returned to Fort Smith after the expedition ended. On December 13, 1864, the First Kansas was redesignated as the Seventy-ninth U.S. Colored Troops (New). The regiment participated in the Action at Ivey’s Ford in January 1865 before transferring to Little Rock, where they were posted until July, and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), where they stayed until mustering out on October 1, 1865. The men were discharged at Fort Leavenworth on October 30, with the regiment having lost 188 men killed or mortally wounded and 166 others to disease.

The Second Kansas Colored Infantry, redesignated the Eighty-third U.S. Colored Troops (New) on December 13, 1864, went from the post at Fort Smith to Little Rock in January and February, then occupied Camden from August to October 1865. The regiment mustered out on October 9, 1865, and was discharged at Leavenworth on November 27, 1865, having lost thirty-four men killed or mortally wounded and 211 to disease.

For additional information:

Christ, Mark K., ed. Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Crawford, Samuel J. Kansas in the Sixties. Ottawa: Kansas Heritage Press, 1994.

Dyer, Frederick. A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion. Des Moines, IA: Dyer Publishing Co., 1908, pp. 1186–1867, 1735–1736.

Nichols, Ronnie A. “The Changing Role of Blacks in the Civil War.” In “All Cut to Pieces and Gone to Hell”: The Civil War, Race Relations, and the Battle of Poison Spring, edited by Mark K. Christ. Little Rock: August House, 2003.

Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Kansas, 1861–’65, Vol. I. Topeka: The Kansas State Printing Company, 1896.

Spurgeon, Ian Michael. Soldiers in the Army of Freedom: The 1st Kansas Colored, The Civil War’s First African American Combat Unit. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014.

Urwin, Gregory J. W. “‘We Cannot Treat Negroes…as Prisoners of War’: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in Civil War Arkansas.” In Civil War Arkansas: Beyond Battles and Leaders, edited by Anne J. Bailey and Daniel E. Sutherland. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Mark K. Christ

Central Arkansas Library System

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Military

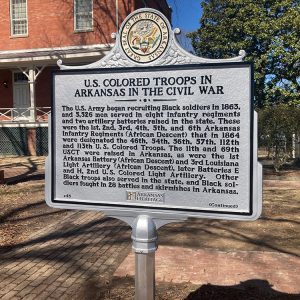

Military Black Union Troops Marker (front)

Black Union Troops Marker (front)  Black Union Troops Marker (back)

Black Union Troops Marker (back)

I am looking for information on a possible relative from the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteers. His name was John Burton.