calsfoundation@cals.org

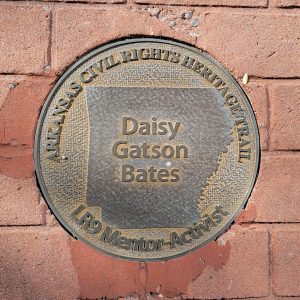

Daisy Lee Gatson Bates (1914?–1999)

Daisy Lee Gatson Bates was a mentor to the Little Rock Nine, the African American students who integrated Central High School in Little Rock in 1957. She and the Little Rock Nine gained national and international recognition for their courage and persistence during the desegregation of Central High when Governor Orval Faubus ordered members of the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the entry of Black students. She and her husband, Lucious Christopher (L. C.) Bates, published the Arkansas State Press, a newspaper dealing primarily with civil rights and other issues in the Black community.

The identity of Daisy Gatson’s birth parents has not been conclusively established; applying for a delayed birth certificate prior to her marriage, she identified Millie Riley and John Gatson as her parents, but in a later interview with writer Janis Kearney, Bates identified her mother as Millie Riley and her father as Hezekiah Gatson; the date of her birth is usually given as November 11, 1914. Hezekiah Gatson fathered six additional children, half-siblings to Daisy. Before the age of seven, she was taken in as a foster child by Susie Smith and Orlee (or Ora Lee) Smith, a mill worker, in Huttig (Union County), three miles from the Louisiana border; her mother was reportedly murdered by three white men when Daisy was young, and her father left her with the Smiths. Gatson attended the segregated schools in Huttig, but it has not been determined how much formal education she received. It is unlikely her education went beyond the ninth grade and may have been no more than four grades.

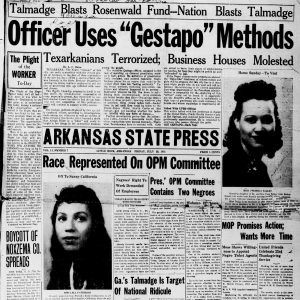

At the age of fifteen, she met her future husband, L. C. Bates, then a traveling salesman living in Memphis, Tennessee. After the death of her foster father, she apparently moved to Memphis in 1932. Little is known about her until she and her future husband moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1941 to start the Arkansas State Press, a weekly statewide newspaper devoted to advocating civil rights for African Americans. Gatson and Bates were married on March 4, 1942, in Fordyce (Dallas County). Although she rarely wrote for the paper, Bates gradually became active in its operations and was named by her husband as city editor in 1945.

As ardent supporters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), both Bates and her husband were active in the Little Rock branch. In 1952, she was elected president of the Arkansas Conference of Branches, the umbrella organization for the state NAACP. She and her husband worked closely with other members of the Little Rock branch as the national strategy of the NAACP shifted in the 1950s from advocating a position of equal funding for segregated programs to outright racial integration.

Although well known in the Black community, Bates came to the attention of white Arkansans as a civil rights advocate in 1956 during the pre-trial proceedings of the federal court case, Aaron v. Cooper, which set the stage for the 1957 desegregation of Central High School.

The case was filed for the purpose of enforcing the rights of Black children in Little Rock to attend schools with whites in accordance with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. Questioned by Leon Catlett, an attorney for the Little Rock school board, Bates refused to allow herself to be called by her first name. She told the attorney, “You addressed me several times this morning by my first name. That is something that is reserved for my intimate friends and my husband. You will refrain from calling me Daisy.” Without hesitating, Catlett shot back, “I won’t call you anything then,” to which Bates responded, “That’s fine.” This challenge to one of white supremacy’s oldest traditions—that of controlling and intimidating African Americans by treating them as though they were children—became part of the front-page story in the next morning’s Arkansas Gazette.

The federal courts at the time allowed the Little Rock school district to set its own pace for desegregation of its public schools, but they could not prevent Bates’s involvement with the first nine students who attended Central High School during the school year of 1957–58. Although Wiley Branton of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) was the local attorney for the NAACP and handled much of the litigation, Bates, in her capacity as president of the Arkansas Conference of Branches, was recognized as the principal spokesperson and leader for the forces behind school desegregation. In this role, she was in constant contact with NAACP leaders and in constant conflict with segregationists using intimidation in Arkansas. For much of the school year, she was in daily contact with the national office of the NAACP in New York as segregationists battled to destroy the NAACP in Arkansas as well as to intimidate her, her husband, and the Little Rock Nine and their families into giving up the struggle. On occasion, individuals attacked the Bateses’ home in Little Rock, forcing them to stand guard nightly.

In recognition of her leadership, the national Associated Press chose her in 1957 as the Woman of the Year in Education and one of the top ten newsmakers in the world. In 1959, as a result of intimidation by news distributors and a boycott by white business owners who withheld advertising, the Bateses were forced to close the Arkansas State Press.

Bates remained at the center of the desegregation battle on behalf of the NAACP and the civil rights movement in Arkansas until June 1960 when she moved to New York to write a memoir of her desegregation experiences in Little Rock, The Long Shadow of Little Rock. She remained president of the Arkansas Conference of Branches until 1961, when she was succeeded by George Howard, Jr., who later became a federal judge. Chosen to fill a vacancy on the national board of the NAACP in 1957, Bates was reelected to successive three-year terms through 1970.

Her prominence as one of the few highly visible female civil rights leaders of the period was recognized by her selection as one of six women chosen to represent the movement in a “Tribute to Women” at the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington on August 28, 1963.

Daisy and L.C. Bates were divorced in February of 1963, but only briefly. They remarried in July of the same year.

In 1968, Bates moved to the all-Black town of Mitchellville (Desha County) to become executive director of that community’s Economic Opportunity Agency, a federal anti-poverty program. She remained there until 1974, commuting to Little Rock on the weekends to be with her husband. This began a new phase in her life that was marked by a commitment to demonstrating that poor African Americans could achieve economic self-sufficiency in partnership with government. Bates secured grants and donations for several improvements in the community, including a sewer system and a Head Start program.

Bates revived the Arkansas State Press in 1984, but it was financially unsuccessful. She sold the paper in 1988 to Janis and Darryl Lunon.

In ill health the last years of her life, Bates died of a heart attack on November 4, 1999, at Baptist Medical Center in Little Rock. She is buried in Haven of Rest Cemetery in Little Rock.

In May 2000, a crowd of more than 2,000 gathered in Robinson Auditorium in Little Rock to honor her memory. At this event, President Bill Clinton acknowledged her achievements, comparing her to a diamond that gets “chipped away in form and shines more brightly.” In 2001, the Arkansas legislature enacted a provision that recognizes the third Monday in February as “Daisy Gatson Bates Day.” Thus, her memory (along with that of President George Washington) is celebrated on that date as an official state holiday. There are streets in various towns in Arkansas, including Little Rock, which bear her name. In February 2012, PBS broadcast the documentary Daisy Bates: First Lady of Little Rock. In 2019, the Arkansas General Assembly passed a law to replace the statues of Uriah M. Rose and James P. Clarke in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the U.S. Capitol with statues of Daisy Bates and Johnny Cash. The statue, produced by Benjamin Victor of Boise, Idaho, was unveiled on May 8, 2024.

For additional information:

Adams, John Lewis. “‘Time for a Showdown: The Partnership of Daisy and L. C. Bates, and the Politics of Gender, Protest and Marriage.” PhD diss., Rutgers University, 2014.

Adams, Kelly R. “Literate Practices in Women’s Memoirs of the Civil Rights Movement.” PhD diss., Arizona State University, 2012.

Alqahtani, Beshaier M. “Representing Black Women’s Activism: Understanding Social Change through Autobiographical Narrations of the Civil Rights Era.” PhD diss., Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 2020.

Barker, Geoff. “Daisy Bates and Mitchellville: A Forgotten Part of the Legacy.” Pulaski County Historical Review 59 (Winter 2011): 112–121.

Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Beals, Melba Pattillo. Warriors Don’t Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock’s Central High. New York: Washington Square Books, 1994.

Calloway-Thomas, Carolyn, and Thurmon Garner. “Daisy Bates and the Little Rock School Crisis: Forging the Way.” Journal of Black Studies 26 (May 1996): 616–628.

Daisy Bates Papers. Special Collections. State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin.

Daisy Bates Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Freemon, Monique, and Lori Amber Roessner. “Our Forgotten Mother: Daisy Bates and Her High School Integration Campaign.” Journalism History 48, no. 3 (2022): 242–265.

Harper, Misti Nicole. “Portrait of an (Invented) Lady: Daisy Gatson Bates and the Politics of Respectability.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 78 (Spring 2019): 32–46.

Huckaby, Elizabeth. Crisis at Central High. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press 1980.

Jacoway, Elizabeth. “Daisy Lee Gatson Bates (1913?–1999): The Quest for Justice.” In Arkansas Women: Their Lives and Times, edited by Cherisse Jones-Branch and Gary T. Edwards. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018.

———. Interview with Daisy Bates. October 11, 1976. Southern Oral History Program, Library of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Kearney, Janis E. Daisy: Between a Rock and a Hard Place. Little Rock: Writing Our World Ppublishing, 2013.

Kirk, John A. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Mitchell, Anne Michelle. “Civil Rights Subjectivities and African American Women’s Autobiographies: The Life-Writings of Daisy Bates, Melba Pattillo Beals, and Anne Moody.” PhD diss., Ohio State University, 2010.

Polokow, Amy. Daisy Bates: Civil Rights Crusader. North Haven, CT: Linnet Books, 2003.

Reed, Linda. “The Legacy of Daisy Bates.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Spring 2000): 76–83.

Stockley, Grif. Daisy Bates: Civil Rights Crusader from Arkansas. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2005.

Thomas, Alex. “Bates Statue Placed in US Capitol.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 9, 2024, pp. 1A, 5A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/may/09/arkansas-national-leaders-unveil-bates-statue-at/ (accessed May 9, 2024).

———. “Bates Towered; Now Statue Will.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 5, 2024, pp. 1A, 10A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/may/04/arkansans-enthusiastic-for-us-capitol-debut-of/ (accessed May 5, 2024).

Wheeler, Durene Imani. “Sisters in the Movement: An Analysis of Schooling, Culture, and Education from 1940–1970 in Three Black Women’s Autobiographies.” PhD diss., Ohio State University, 2004.

Grif Stockley

Butler Center for Arkansas Studies

Thank you for helping to keep the dreams and visions alive surrounding L. C. and Daisy Bates. Our family appreciates your contributions. They contributed so much to our great American culture through their work as journalists and activists.