calsfoundation@cals.org

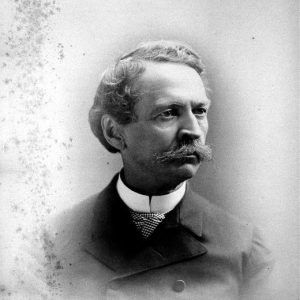

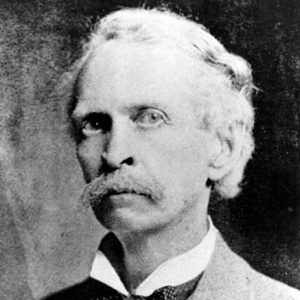

Uriah Milton Rose (1834–1913)

Uriah Milton Rose was a nationally prominent attorney who practiced in Little Rock (Pulaski County) for more than forty years at what is now known as the Rose Law Firm. He was a founder and president of both the Arkansas Bar Association and the American Bar Association, and he was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt as an ambassador for the United States to the Second Hague Peace Conference in 1907.

U. M. Rose was born on March 5, 1834, in Bradfordsville, Kentucky, to Nancy and Joseph Rose. His father was a physician. He was his parents’ third son and had two half-siblings from his father’s first marriage to a Miss Armstrong from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Rose’s mother died in 1848, and his father died the following April. After his father’s death, the family’s home went into the hands of an administrator who was charged with paying the family debts, which exceeded the assets. The children were thrown out. Rose’s father had incurred considerable debt in starting a glass manufacturing plant in Pittsburgh, which he struggled to pay his entire life. Rose found work in the village store, where he also slept. A few years later, he studied law at Transylvania University at Lexington, graduating in 1853.

While in law school, Rose met his future wife, Margaret T. Gibbs. They married on October 25, 1853. Rose found the cold Kentucky winters especially difficult, thus near the end of his formal legal study, and after reading a newspaper article about Batesville (Independence County) which ignited Rose’s imagination, he convinced his new wife that a move to Arkansas was desirable. On December 5, 1853, a few months after their marriage, the couple, along with Rose’s brother-in-law, William T. Gibbs, another young lawyer who was making the move with them, set out for Batesville to start a new life in a state where none of them knew a single person. Rose studied Arkansas law for two years before he formed a partnership with Gibbs.

While living in Batesville from 1853 to 1862, the Roses had three children. The family moved to Little Rock after the Civil War in 1865 and had four more children.

Rose was not in favor of secession by the state on very practical grounds. He did not believe the Southern states could win a war with the states that remained in the union; however, after it became clear that secession was inevitable, he sided with his fellow Arkansans. Rose was not suited for physical battle and was not commissioned into the Confederate army, but his intellect and education led to an assignment to collect the records of Arkansas soldiers serving in the Confederate army. As such, he traveled to Richmond, Virginia, during the war to record the names of all Arkansans participating in the Confederacy. After weeks of painstakingly recording every name, he arranged to have the records transported to Little Rock. In transit, the records were stored in a warehouse to wait for a time to safely move them across the Mississippi River; however, the warehouse caught fire, and all the records were lost.

Governor Elias Conway appointed Rose chancellor of the Court of Chancery of Pulaski County in 1860. The chancellor’s office was the only such office in the state and thus had statewide jurisdiction.

Rose built a reputation as an intelligent, articulate attorney. After he moved to Little Rock, his name was placed in nomination before the Arkansas General Assembly for the position of U.S. senator in the fall of 1877. After several votes which did not result in an election, he notified the legislature that he did not desire the position, and his name was dropped. Rose told the legislators that he did not feel he could be of service and that such office offered him no happiness.

Elisha Baxter asked Rose to argue his case to President Ulysses S. Grant during the Brooks-Baxter War, a “war” between two contestants for the office of governor of the state. Rose accepted Baxter’s request and traveled to Washington DC to appear before Attorney General George Williams in May 1874. Inasmuch as the Federal troops continued to control the balance of political power in the state, both contestants in the war realized that the ultimate decision could be made by President Grant. Baxter’s decision to employ Rose’s talents rather than force of arms proved crucial to his success.

Shortly after Rose’s move to Little Rock in 1865, Rose and Judge George C. Watkins, formerly chief justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court, opened the law office of Watkins and Rose. The pair practiced together for six years, until Judge Watkins’s death in 1872. Rose’s son George joined the firm in 1881, and other attorneys joined and left the practice over the years. The Rose name was constant, and in 1980, the firm became known simply as the Rose Law Firm. Rose appeared before the supreme courts of both Arkansas and the United States on several occasions, arguing cases such as those related to the ownership of downtown Hot Springs (Garland County) and Little Rock, the status of a promissory note given for the purchase price of a slave who was later freed, and the rights of bondholders of railroads built in the state.

Rose was among the original seventy-five members who founded the American Bar Association in August 1878 in Saratoga Springs, New York. He was the only member from Arkansas. In August 1901, he was elected president of the association.

On May 24, 1882, sixty-eight lawyers from across the state met at Rose’s suggestion and formed the Arkansas State Bar Association. Rose was elected chairman of the association’s first executive committee and, between 1898 and 1899, served as president.

In October 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt took an extensive trip across the South, including Little Rock, where he attended a luncheon. At that luncheon, Rose toasted the president, who responded by saying, “Judge Rose stands today as one of that group of eminent American Citizens, eminent for their services to the whole country, whom we know as the leaders of the American bar.”

The following year, President Roosevelt, who was in the process of selecting representatives to a second conference to discuss international rules of war, asked Rose to come to Washington in February 1906 to discuss it with him. He appointed Rose as a delegate to the Second Hague Peace Conference held in 1907. The delegates appointed by Roosevelt were given the status of ambassadors to enhance their ability to represent the United States.

After a fall in his office in June, Rose died on August 12, 1913. Out of respect for him, all of the state and county offices were closed for the day of his funeral. He is buried in the Oakland Cemetery in Little Rock.

In 1915, the Arkansas General Assembly voted to place a marble statue of Rose in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol. Justice Felix Frankfurter of the U.S. Supreme Court wrote, “[I]n my early years at the bar U. M. Rose was one of the luminaries of our profession—not merely a very distinguished practitioner but a highly cultivated, philosophical student of civilization and of the role of law and the lawyers in progress of civilization.” In 2019, the state legislature voted to replace the statues of Rose and James Paul Clarke at the U.S. Capitol with statues of Daisy Bates and Johnny Cash.

For additional information:

Bird, Allen W., II. “U. M. Rose: Arkansas Attorney.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 64 (Summer 2005): 171–205.

Harrell, John M. The Brooks and Baxter War—A History of the Reconstruction Period in Arkansas. St. Louis: Slawson Printing Co., 1893. Online at https://archive.org/details/brooksbaxterwarh00harr/page/n3/mode/2up (accessed March 6, 2024).

Rogers, James G. American Bar Leaders: Biographies of the Presidents of the American Bar Association, 1878–1928. Chicago: American Bar Association, 1932.

Rose, George B., ed. U. M. Rose—Memoirs and Addresses. Chicago: George I. Jones, 1914.

Allen W. Bird II

Little Rock, Arkansas

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.